“It was the best of times, it was the blurst of times?” Perhaps not anymore, if this Ig Nobel-worthy analysis of the infinite monkey theorem is to be believed. For the uninitiated, the idea is that if you had an infinite number of monkeys randomly typing on an infinite number of keyboards, eventually the complete works of Shakespeare or some other famous writer would appear. It’s always been meant to be taken figuratively as a demonstration of the power of time and randomness, but some people just can’t leave well enough alone. The research, which we hope was undertaken with tongue firmly planted in cheek, reveals that it would take longer than the amount of time left before the heat death of the universe for either a single monkey or even all 200,000 chimpanzees in the world today to type the 884,647 words of Shakespeare’s complete works in the proper order.

We feel like they missed the point completely, since this is supposed to be about an infinite number of monkeys. But if they insist on sticking with real-world force monkey labor, what would really be interesting is an economic analysis of project. How much space would 200,000 chimps need? What would the energy requirements be in terms of food in and waste out? What about electricity so the monkeys can see what they’re doing? If we’re using typewriters, how much paper do we need, and how much land will be deforested for it? Seems like you’ll need replacement chimps as they age out, so how do you make sure the chimps “mix and mingle,” so to speak? And how do you account for maternity and presumably paternity leave? Also, who’s checking the output? Seems like we’d have to employ humans to do this, so what are the economic factors associated with that? Inquiring minds want to know.

Speaking of ridiculous calculations, when your company racks up a fine that only makes sense in exponential notation, you know we’ve reached new levels of stupidity. But here we are, as a Russian court has imposed a two-undecillion rouble fine on Google for blocking access to Russian state media channels. That’s 2×1036 roubles, or about 2×1033 US dollars at current exchange rates. If you’re British and think a billion is a million million, then undecillion means something different entirely, but we don’t have the energy to work that out right now. Regardless, it’s a lot, and given that the total GPD of the entire planet was estimated to be about 100×1012 dollars in 2022, Google better get busy raising the money. We’d prefer they don’t do it the totally-not-evil way they usually do, so it might be best to seek alternate methods. Maybe a bake sale?

A couple of weeks back we sang the praises of SpaceX after they managed to absolutely nail the landing of the Starship Heavy booster after its fifth test flight by managing to pluck it from the air while it floated back to the launch pad. But the amazing engineering success was very close to disaster according to Elon Musk himself, who discussed the details online. Apparently SpaceX engineers shared with him that they were scared about the “spin gas abort” configuration on Heavy prior to launch, and that they were one second away from aborting the “chopsticks” landing in favor of crashing the booster into the ground in front of the launch pad. They also expressed fears about spot welds on a chine on the booster, which actually did rip off during descent and could have fouled on the tower during the catch. But success is a hell of a deodorant, as they say, and it’s hard to argue with how good the landing looked despite the risks.

We saw a couple of interesting stories on humanoid robots this week, including one about a robot with a “human-like gait.” The bot is from China’s EnginAI Robotics and while its gait looks pretty good, there’s still a significant uncanny valley thing going on there, at least for us. And really, what’s the point? Especially when you look at something like this new Atlas demo, which really leans into its inhuman gait to get work done efficiently. You be the judge.

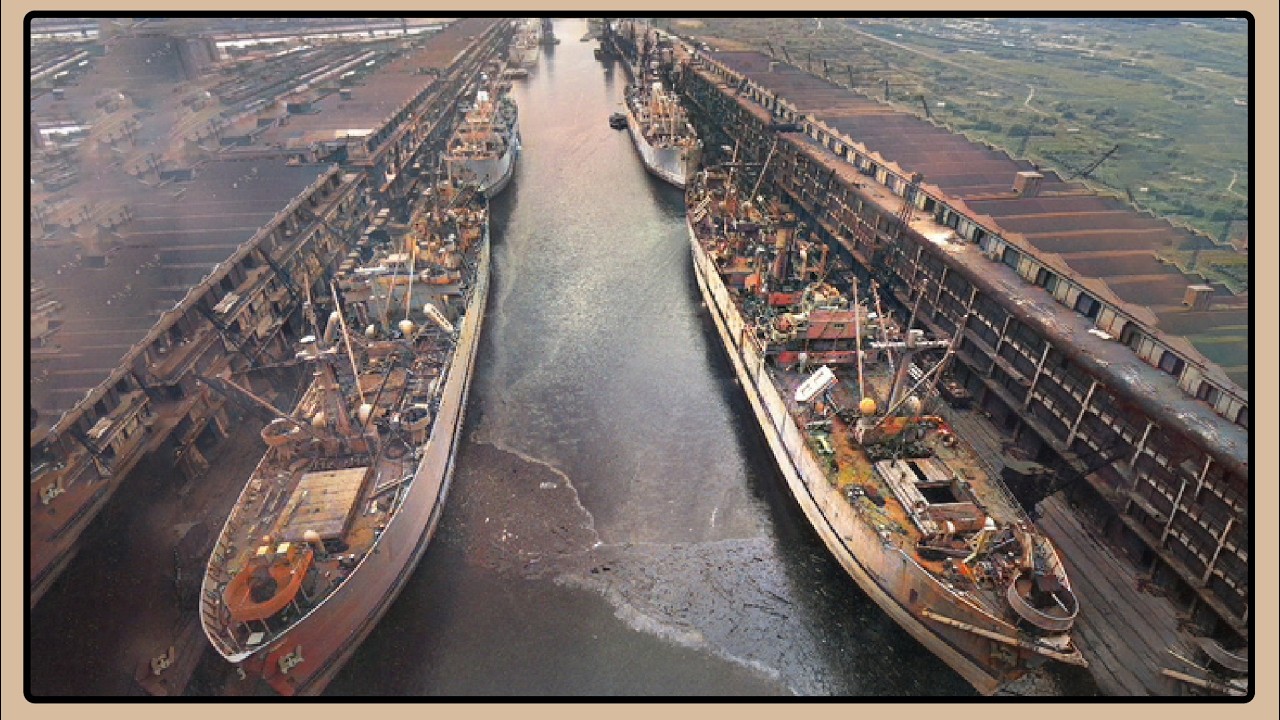

And finally, we’ve always been amazed by Liberty ships, the class of rapidly produced cargo ships produced by the United States to support the British war effort during WWII. Simple in design though they were, the fact that US shipbuilders were able to ramp up production of these vessels to the point where they were building a ship every eight hours has always been fascinating to us. But it’s often true that speed kills, and this video shows the fatal flaw in Liberty ship design that led to the loss of some of the early ships in the class. The short video details the all-welded construction of the ships, a significant advancement at the time but which wasn’t the cause of the hull cracks that led to the loss of some ships. We won’t spoil the story, though. Enjoy.

“If you’re British and think a billion is a million million”

No, we don’t. Back in Victorian times there was a British Billion of 10^12, back then we called 10^9 a Milliard. Nowadays every Brit regards a billion as 10^9, we standardised to match the rest of the world. Now come on America, accept that the element with atomic number 13 is pronounced, and written, aluminium.

Long scale was only officially dropped in Britain in 1974. Long ways away from Victorian. Short scale (billion = thousand million) is way more recent than long.

As for aluminum, they’re both acceptable spellings by IUPAC, just like cesium and caesium. The dude who isolated it called it both, so it’s both.

What about Unobtainium? Surely that would be known as Unobtainum in the US?

Element naming’s totally standardized by now, that’s silly. Aluminum as an element name from the early 1800s doesn’t stand out a ton (lanthanum, tantalum, platinum, molybdenum) and the worst element name (helium, the only -ium non-metal ) happened years later because it came from an astronomer.

In fact, the ‘-um’ spelling makes the pronunciation in English identical to its oxide (alumina), whereas the ‘-ium’ spelling always differs (either in stress, with ah-loo-MIN-ium) or… like, everything (with al-yoo-MIN-ium).

I mean, jeez, if you’re going to criticize the US for elements, use iodine. That one’s just unforgivable.

Doesn’t stand out a British ton or US ton?

Also if you’re European, you still call 10^9 something like milliard of miljard. A billion still.is 10^12 then.

Thank you for thinking of us, but we Brits have been using the short billion for decades now.

I will spoil the story, because it’s not much of a story. TL;DW: The steel used for the ships suffered an excessive loss of ductility at low temperatures and was prone to brittle fracture during winter.

Thank you!

Same thing happened with the Titanic and other ships of that era.

No, the titanic had a flaw with it’s riveting procedure, leading to them having a weaker strength. iirc the rivets were driven cold in multiple strikes due to cost reductions. they were all hammered in by hand in that era. proper procedure is to drive them while they are red hot.

Thank you.

Doesn’t matter how many monkeys you have — it’s the proofreading that’ll be the real bi#$h

Which is why you’d use bots, instead. (AI monkeybots? MonkAIs?)

Consider: a single page holds up to 18,000 characters. By ignoring lower-case and numbers, each character could be one of 32 (2^5) values.

So, each page can be represented by a single value, of 32^18000. A stonking large number, but not infinity.

If you have 32^18000 monkeybots, each simply taking their own number and converting it to text, you would produce all the pages for Shakespeare’s plays. You’d also produce every page of every other book, along with a myriad of pages that are ALMOST correct but for a few missprints.

Which is why you also need AI “detector” bots, to sort through the pile and filter the results.

The “filter” bit is interesting because really, the theorem is a bit silly: saying that “the content of a random output eventually contains all human works when you collect it over time” is, well, pointless – think of pointing an antenna towards the Voyager probes and saying “look, I’ve got their signal” when it’s totally buried in the noise: yeah, the data might conceivably be there, but unless you know what you’re looking for, you’ll never find it.

And if you then ask “what are the chances you would grab the selected works of Shakespeare from the output of an N of monkeys over time t”, the answer actually tends to zero as N/t go to infinity, not one.

For all you youngsters out there: (the Infinite Number of Monkeys Apple II demo)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IfMDWhc_ohU

I wonder if the monkey would have to type the entire thing before checking it against the original. Wouldn’t the first word already give you a clue?

Monkey typing must be a lengthy process…

We already have an upper limit on how long it would take an infinite number of chimpanzees to reproduce the works of Shakespeare. It took the universe roughly 13.7 billion years to produce the complete works of Shakespeare, and most of that time was spent making the chimpanzees from scratch; The Tempest came relatively quickly after that. If we’ve already got the Chimps and the typewriters to start with, it shouldn’t take nearly as long.

If your number of monkeys was truly infinite, then one (or more) of them would type the works of Shakespeare nearly instantly. Or at least no longer than it takes the luckiest and fastest monkey to type it.

I won’t watch the video then, whatever.

The way that atlas bot turns its head and and torso so aggressively with no rotational limit is pure nightmare fuel.

Or as Bob Newhart reported…

To be or not to be, that is the gzorninplotz.