Recently China’s new CHIEF hypergravity facility came online to begin research projects after beginning construction in 2018. Standing for Centrifugal Hypergravity and Interdisciplinary Experiment Facility the name covers basically what it is about: using centrifuges immense acceleration can be generated. With gravity defined as an acceleration on Earth of 1 g, hypergravity is thus a force of gravity >1 g. This is distinct from simple pressure as in e.g. a hydraulic press, as gravitational acceleration directly affects the object and defines characteristics such as its effective mass. This is highly relevant for many disciplines, including space flight, deep ocean exploration, materials science and aeronautics.

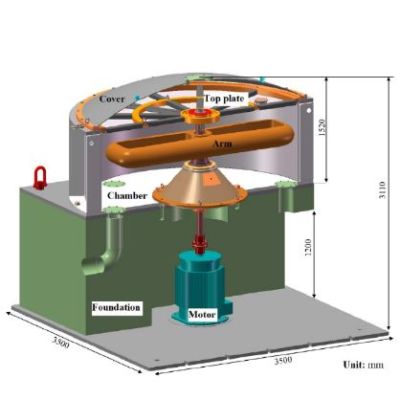

While humans can take a g-force (g0) of about 9 g0 (88 m/s2) sustained in the case of trained fighter pilots, the acceleration generated by CHIEF’s two centrifuges is significantly above that, able to reach hundreds of g. For details of these centrifuges, this preprint article by [Jianyong Liu] et al. from April 2024 shows the construction of these centrifuges and the engineering that goes into their operation, especially the aerodynamic characteristics. Both air pressure (30 – 101 kPa) and arm velocity (200 – 1000 g) are considered, with the risks being overpressure and resonance, which if not designed for can obliterate such a centrifuge.

The acceleration of CHIEF is said to max out at 1,900 gravity tons (gt, weight of one ton due to gravity), which is significantly more than the 1,200 gt of the US Army Corps of Engineers’ hypergravity facility.

Lets hope its not tofu steg

This brings back memories. The first resonance cascade was 19th November 1998 exactly 26 years and 1 day ago! I was working as young PhD in New Mexico and it happened during a test in the AMS chamber. Luckily me and my colleages were okay.

LOL this comment had me rollin lol when i was reading the statement it reminded me of HL1 then i saw the user name LOL

Wisely done Mr. Freeman!

I was lost, so I had to research. Seems my hobbies just didn’t intersect properly to have encountered this info. Glad you are safe and able to continue your endeavors.

Well rules for engagement with such weapon are already in place.Now we just have to figure out who we can and can’t flatten.Rules,dammit man!

In terms of just gravities of acceleration, 1900 g is nothing to write home about. Cheap student laboratory centrifuges get to 200 000 g and the big boy ones get to 1 million g.

Comparing to human accelerations is specious: 1900 g will turn a human into a bloody puddle, so not relevant here.

So what is it about the scale of this that’s important? It’s obviously not just the g force. What can it do that smaller ones can’t? (besides the obvious ‘Duh, it holds bigger things’.)

1 million g? Really? Wouldn’t that be enough to cause fusion to occur, since the mass of the sun is about 330,000 times that of earth. That would equate to “only” 330,000 g, right?

Take a look at this paper talking about a hundred million gravity produced by a centrifuge: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18699609/

And yet, there are, for example, the Beckman Optima Max-XP or Sorvall MTX150 ultracentrifuges, that do exactly that.

1 million g means one million times the acceleration produced by earths gravity, not the pressure produced by being at the center of a body one million times the mass of the earth.

But there would be a 1:1 relationship between the acceleration and the pressure, right?

The sun us a circular mass, so all that force that it generates with that gravity is focused into one point. As gravity or even force does not have a ‘minimum size’, it means that all that force is focused onto an infinitely small point. If a quark moves through that point, the focus of that force will move through the ‘insides’ of the quark, the focus point is infinitely smaller than the quark.

I really have no clue what that all means for the quark, or the proton, neutron or electron that it’s part of. :+) But it must mean something.

In the case of a centrifuge, all that force is not pointing towards an infinitely small point in spacetime, but will be parallel and spread out on a plane. If a quark move through it, it will experience orders of magnitude less of that force.

That seems to me to be something that can cause a difference in behavior.

For the rest, I have no clue what I’m talking about and I’m sure that any physicist can shoot holes in my theory and can give a better explanation. ;)

Even at the center of the sun, you need about 15 million degrees to initiate hydrogen-hydrogen fusion. You need way more heat on Earth because of the absence of that gravity field.

Gravity field in center of star is close to zero. Look up Newton’s shell theorem.

The pressure at the center of the star is caused by its gravitational field, even if that gravitational force is not acting directly on the center.

It looks like the author conflated acceleration (g) and force (gt). I’ve never done anything with or learned anything about centrifuges, but I’d guess that while 1900g isn’t impressive, 1900gt is.

1900 tonnes is half the mass of SpaceX’s superheavy, or about a tenth that of a modest ferry boat, and well within the capacity of many lift cranes. In itself, that amount of force is not so special. The accelerations and forces involved are high, but not crazy. Heck, even the lame Spin Launch centrifugal launcher concept is in this ballpark.

So, again, what makes this Chinese spin on things noteworthy?

It’s not just the g’s, it’s how much mass how can hold at that rate.

1900gt’s is the equivalent of 1ton at 1900 g. A 20 gram sample in one of those million g centrifuges would be 20 gravity tons, about a tenth as much as they are proposing. You’d have to load it up with 1.9kg to get to the same 1900gt figure

The linked article explains the uses for this. It’s proposing testing scale models of systems for various purposes.

You’d have a lot of trouble fitting a scale model in a laboratory centrifuge. And you’d have a lot more trouble trying to fit an object of any kind in the ones that go up to a million g.

Goku trained in just 100g to become a super Saiyan. 1900g is really a lot.

One of my favorite fair rides is the Gravitron/Spaceship 3000. Sometimes the ride operator will move around and do tricks during the ride, and it occured to me that they must be quite strong, thus it could be advantageous to do training in a centrifugal setting to increase the forces you’re working against. Even just walking in one often enough would make walking in 1g feel quite easy.

You can get 800,000 g’s in your lab with the basic ultra-centrifuge. A million g’s if you spend a little more. A desktop BECKMAN COULTER OPTIMA MAX-XP ULTRA-CENTRIFUGE on eBay is $12,000 and 1 million g’s. You can find floor units from the 1980’s cheap.

This prompts the question, in Ultra versus Hyper who wins?

“gravitational acceleration directly affects the object and defines characteristics such as its effective mass”

Do you mean the weight? Mass does not change based on gravity.

Well, we could spin it at relativistic speed :D

Interdasting that they would use such a contrived English acronym (certainly a backronym, US military-style)… I wonder why that was chosen.

Maybe the same reason they chose ‘FAST’ for the world’s largest radio telescope: International bragging rights.

1900G is an odd target number, right? Missiles are in the dozens to a hundred or so G, and artillery shells are in the 10,000s+ of G, so what’s it for? And yeah sure you don’t have to run it at full speed. Also is that 1900 g empty?

Very interesting.

Being such a heavy mass rotating, will it change Earth rotation (speed and direction) signifincantly? This is similar to the rocket launches that are taking advance of the Earth rotation, thus slowing it down.

Significantly? No. This is like the “get everyone in China to jump at the same time” thing. The Earth is really really big compared to everything human have made. If we did want to change the speed of rotation of the Earth we’d probably do it by making or demolishing mountains rather than by spinning things.

“arm velocity (200 – 1000 g) ”

I guess AI used to translate or write this was confused. Velocity not measured in gs

Whole article is full of these oddities. Not to mention it’s unclear what so unique about this centrifuge, it is comparable to what USSR had if what is written correct. But this looks like bad translation or AI hallutinations

OK so it has more g, but the difference is relevant to what sort of work exactly? Let me guess, their nuclear armed hypersonic cruise missile program, because that is where you see massive g, during intercept avoidance maneuvers. #DeathTech

Can they bring this thing to me so I can get my rocket out of this tree,Lol!