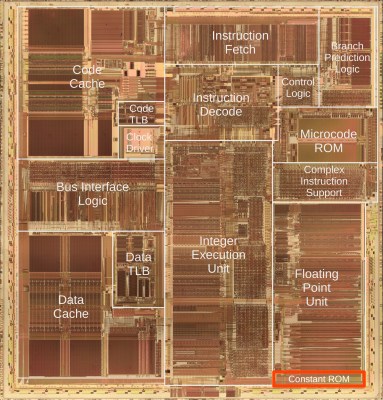

Released in 1993, Intel’s Pentium processor was a marvel of technological progress. Its floating point unit (FPU) was a big improvement over its predecessors that still used the venerable CORDIC algorithm. In a recent blog post [Ken Shirriff] takes an up-close look at the FPU and associated ROMs in the Pentium die that enable its use of polynomials. Even with 3.1 million transistors, the Pentium die is still on a large enough process node that it can be readily analyzed with an optical microscope.

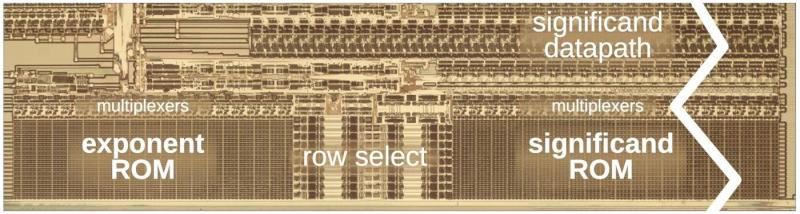

In the blog post, [Ken] shows how you can see the constants in each ROM section, with each bit set as either a transistor (‘1’) or no transistor (‘0’), making read-out very easy. The example looks at the constant of pi, which the Pentium’s FPU has stored as a version with no fewer than 67 significand bits along with its exponent.

Multiplexer circuitry allows for the selection of the appropriate entry in the ROM. The exponent section always takes up 18 bits (1 for the significand sign). The significand section is actually 68 bits total, but it starts with a mysterious first bit with no apparent purpose.

After analyzing and transcribing the 304 total constants like this, [Ken] explains how these constants are used with polynomial approximations. This feature allows the Pentium’s FPU to be about 2-3 times faster than the 486 with CORDIC, giving even home users access to significant FPU features a few years before the battle of MMX, 3DNow!, SSE, and today’s AVX extensions began.

Featured image: A diagram of the constant ROM and supporting circuitry. Most of the significand ROM has been cut out to make it fit. (Credit: Ken Shirriff)

Amazing article and thanks for telling us Ken’s work! The comments on this site are slowly filling with information about how some constants came to be. Hope soon all ROM entries and how they were generated will be deciphered.

Amazing you can read it with a microscope. The AMD9511 from the early 1980’s did 16 and 32 bit arithmetic and 32 bit FP and was easy to interface. Push arguments to an internal stack and send a command. It used Chebyshev Polynomials for trig and hyperbolic functions – for $350 1980 dollars, $1340 today! (Wow, that makes me feel old!)

That’s pretty cool because JPL only uses 15 digits for interplanetary navigation 😆

And you inly need 40 for calculating with Atom precision on a Universe scale.

15 decimal digits, not binary digits…