If you’re gonna be a hacker eventually you’re gonna have to write code. And if you write code eventually you’re gonna have to deal with concurrency. Concurrency is what we call it when parts of our program run at the same time. That could be because of something fairly straightforward, like multiple threads, or multiple processes; or something a little more complicated such as event loops, asynchronous or non-blocking I/O, interrupts and signal handlers, re-entrancy, co-routines / fibers / green threads, job queues, DMA and hardware level concurrency, speculative or out-of-order execution at CPU-level, time-sharing on single-core systems, or parallel execution on multi-core systems. There are just so many ways to get tied up with concurrency.

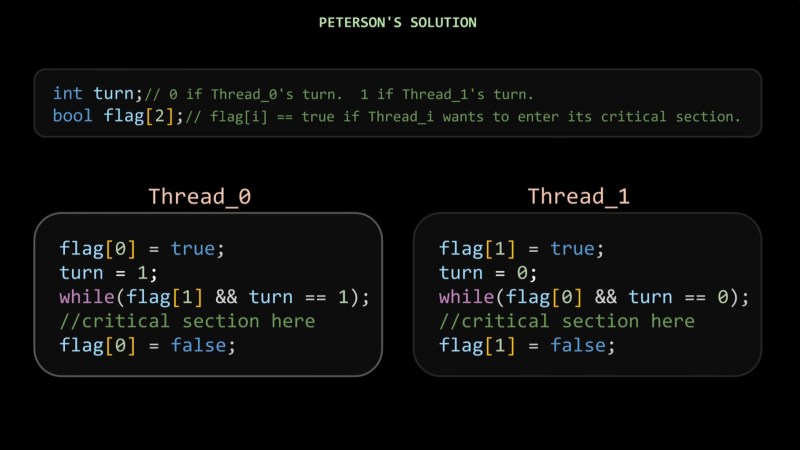

In this video from [Core Dumped] we learn about The ’80s Algorithm to Avoid Race Conditions (and Why It Failed). This video explains what a race condition looks like and talks through what the critical section is and approaches to protecting it. This video introduces an old approach to protect the critical section first invented in 1981 known as Peterson’s solution, but then goes on to explain how Peterson’s solution is no longer reliable as much has changed since the 1980s, particularly compilers will reorganize instructions and CPUs may run code out of order. So there is no free lunch and if you have to deal with concurrency you’re going to want some kind of support for a mutex of some type. Your programming language and its standard library probably have various types of locks available and if not you can use something like flock (also available as a syscall, to complement the POSIX fcntl), which may be available on your platform.

If you’re interested in contemporary takes on concurrency you might like to read Amiga, Interrupted: A Fresh Take On Amiga OS or The Linux Scheduler And How It Handles More Cores.

When you tell them to!

Which is by default, when optimizations are on. Normal non-thread-crossing, non-system-register-touching code can be optimized in various and delightful ways, and developers want performance by default, so that is the default. By not adding special keywords, you are telling the compiler “hey, here’s some code, have fun with it!”

When you use keywords like

volatile,atomicand so on (among others, or your regional platform and language equivalents), you’re specifying that given statements or memory locations must be executed or accessed in order. Which may create a sequence point, memory barrier, emit memory protection instructions/modifiers (LOCKetc.), even cache flushes.Which is why, if you peek inside the header files of a typical MCU for example, you see a ton of

(*(volatile uint8_t*)REGISTER_ADDR)or something like that, to access system registers, which affect system state; and system state is ordered, so the accesses must be as well. Also that the values may change from time to time, so the compiler knows to always read this location, rather than e.g. cache it in a register.And yep, you have your pick of solutions: you can implement your own entirely, given

volatileandatomic(and friends) primitives, in your language of choice; but on a hosted environment, you should probably use library or OS calls — though they vary in weight, scope and functionality, and often aren’t well documented in relation to what you’re doing (description focused rather than example/application focused docs; “Wikipedia syndrome”).I feel like the biggest barrier to understanding concurrency, is no one ever discusses it in concrete terms. When the hell do I want a

LOCK MOV AX, ..., and what’s the LOCK pin on the CPU even for? What does the compiler actually do withvolatile int? What’sATOMIC_BLOCK()and why do I care what argument goes in it? What’s a “critical section”? What’s a lock? What’s a mutex? What OS calls are naturally blocking (and with what fairness rules), and which are unsafe? Are file accesses thread-safe? Network files?Some of these questions, you can solve (i.e. by yourself, from the ground up) with careful reading of hardware diagrams and ISA docs, or disassembling/decompiling sample code, libraries, or occasionally OS components (sometimes, to varying difficulty), plus a generous helping of “just reasoning it out” (e.g., if variable X were modified at any point in a passage involving it, could that create a problem?). There’s surprisingly little help from the usual suspects: concurrency is (shockingly uniformly) provided in the abstract, so sure you can understand a mutex is made from a couple of locks or whatever, but that only leaves you wondering what a lock is, and so on. Instead of turtles all the way down, it’s one turtle stuck spinning upside down…

(For my part, I’ve soaked this up slowly over many years, and, in the course of various projects, encountered and proven most every edge case for the languages and platforms I’ve used; at least for the limited sorts of projects I’ve made. And, if you’re regularly inspecting your assembly output to reinforce your understanding of what it is you’re doing, you’ll see the inlined

ATOMIC_BLOCK()code for example, and understand intuitively on a machine level, what it’s doing.)The C volatile keyword is widely misunderstood. It declares that the “contents” of a variable can change in ways the compiler cannot “detect”, and hence it cannot be “cached” in a register. And that’s all.

From https://en.cppreference.com/w/c/language/volatile.html

“Note that volatile variables are not suitable for communication between threads; they do not offer atomicity, synchronization, or memory ordering. A read from a volatile variable that is modified by another thread without synchronization or concurrent modification from two unsynchronized threads is undefined behavior due to a data race. “

Not sure why this article is on HaD, but I’ll comment anyway.

I’ve been programing for a long time (over half a century..) and one of the biggest problems I’ve had with programming staff – and programs we bought – is that so many programmers simply don’t get concurrency – they can’t design for it, write it, test for it, or debug it.. It’s like a mental conceptualization point just beyond them.. Sort of like some people can’t make the leap to algebra, or understanding calculus.

At the retail – non mainframe – level it was noticeable when developers started doing multi threaded programs that the quality dropped noticeably.. It even got worse in 1995/96 when the boards with 2 Pentium pro chips were popular – it was the first time many developers had programs actually running at the SAME time..

Unfortunately, exactly the same issue is still well alive today. Many current developers have no idea how to safely put together multiple threads that might be simultaneously running, or how to design the software in the first place.. And it isn’t something we teach well (if at all) at uni..

I don’t know where you are from but in France the software engineering courses talk about low level/system programling and concurency a lot, even without a specialization in embedded systems

The courses do in US as well, but many folks who are software engineers did not get degrees in software engineering. (I’d hazard to say ‘most’.)

yes – you can do it at uni- but most people don’t! You can certainly do a BSc in computing and not touch it at all..

In France do the computer science courses also work ‘close to the metal’?

In the USA that’s not remotely true.

Some CS departments are in the GD business school (spit), hand out BAs as ‘certificates of 4 year party’, grad is certified to have high alcohol tolerance.

Don’t hire those CS grads.

If you know how to interview, you won’t anyhow, are generally clowns.

The best CS programs are out of Engineering schools.

Next best is (usually spun) out of math, watch for theoreticians who never actually code.

Worst is business, those are, at best, digital janitor training (IT, not CS).

Never hire CS people who didn’t code before they started college.

‘How many programming languages did you know when you finished HS’ is a pass/fail interview question.

Doesn’t matter if they have a college degree.

Used to have an ‘old folks exception’, but they have all aged out of talent pool.

Would you hire a musician who didn’t play an instrument before they somehow got into music school? (Voice counts as instrument).

If they never code and love the 34th normal form, run away.

Send them to your competitors.

That’s a net negative worker, guaranteed.

Well, programmer != engineer.

Hardware engineers have no problem with concurrency, since all their systems are concurrent.

They do still have problems with /asynchronous/ digital circuits, since they really are a pig compared with (clocked) synchronous circuits.

They also recognise that in circuits with multiple clocks (or even physically large circuits) a single clock doesn’t necessarily happen at the “same time” due to the pesky speed of light constraints.

Hardware engineers are usually much worse at embedded software than actual software engineers, because concurrency built from sequential threads isn’t the same as concurrency built from blocks of hardware. I’ve lost count of the number of race conditions in embedded software written by hardware engineers.

Unfortunately, also, most of the time, hardware engineers think embedded software engineers are just failed hardware engineers and thus prone to ignoring advice from the software side. Their solutions are usually along the lines of:

Increase CPU frequency.

Lock interrupts.

Add delays.

Don’t forget “tweak thread/interrupt priorities”.

Adding a delay is the software version of a 74123 monostable.

You can indeed find bad engineers everywhere; “mensch ist mensch”. However, I’ve found hardware engineers tend to comprehend events processed by an FSM better than softies. Softies, if they have come across the concept, say things like “ISTR FSMs being used in compilers”.

1995/1996 was also about the time that Windows switched from cooperative multi-tasking to pre-emptive.

I was going to make a guess about why this might be. My first thought is that developers just don’t practise with real world examples.

My experience is not as great as yours, but I too have had to dig into others’ attempts at parallel processing.

One case in particular stands out: the resident “god among programmers” had implemented a “multithreaded communication stack” that all of us peons had to leave alone, just don’t even think of looking there. Well eventually the programming god moved on to pastures new and the communication stack needed maintenance. I analysed to programming god’s work and found that although it did start threads it didn’t even put the work units onto those threads, it was effectively single threaded and the programming god hadn’t even noticed let alone tested.

not uncommon.. By the way – if you ever run into anyone saying ‘don’t even look at that code’ that is the code you should look at first..

Oh, come on … Just write you app in Rust… There no more problems :) :rolleyes:

The first 15 years of my career (right out of college) was writing/maintaining real-time applications using VRTX for substation/hydro/comm RTUs we designed and built. In C of course. Fun stuff.

I’m late to the party, but most of the problems with concurrency come from the stupid old adage of make it work then make it fast, as if you can “just thread it later”. There are some problem/solution combinations where this can work, but its more the exception than the rule.

Threading requires a completly different architecture from the beginning. Known sync points, that break down into classical sync problems. Structuring the program to follow these leads to maintainable performant, threaded code.

I’ll also say the video author has no understanding of optimization. None. So while I do appreciate his breakdown of the issues, his handwaving at optimization is pretty sad. That doesn’t mean there’s a way to make petersons work on multicore systems. If there were, we’d be using that.

Oh, and atomics aren’t the be all end all. There are many wrong “solutions” out there because atomics are still limited.(in what they can do – theres not an atomic for every operation you’d like to be atomic!). There are some very clever solutions though. They should most definately be used when they fit.

Have a look at Lava MuMu, it is a fully concurrent language/engine

https://lib.rs/crates/mumu

It is very performant too (way faster than JavaScript/Node/V8).

That language will be built on top of the primitive operations discussed here. To that extent it is just “syntactic sugar”.

More is necessary for concurrent systems. I have no opinion whether that language is better than others in that respect.

People interested in such systems should understand Tony Hoare’s CSP (from 1976!), and how the concepts have been implemented in languages such as Go, xC, Occam.

It is not just a language it is a fully concurrent system. Please will you explain what you meant by “More is necessary for concurrent systems”?

See the paragraph starting “People interested in such systems should understand…”

‘Very performant’ is now ‘better than JS and associated pig F libraries’?

That’s a pitiful low bar.

Locking via the compiler, around all shared resource access isn’t a great solution.

If you lock individual memory ranges, you’ll be coding deadlocks all day long.

Threads will spend all day waiting if you lock all of memory.

Files same same.

All about consistent order of locking…

So now the compiler is looking into all functions invoked, to try and build a lock list to sort first.

Which sucks, locking everything early.

Thanks for the article. You have a typo “fnctl” that should be “fcntl”. The link to the man page there is correct, though.

thanks!

One of the hardest things to get right and worse to maintain. You can be overly cautious, but then you might cause stalls.

Just finding an atomic primitive can be an issue. Let’s say you use file locking, turns out that not all file systems behave the same way. Network mapped drive on windows nixed my efforts once.

I suppose for a decade or more, this has been solved by database implementers, you hope they did not mess up (I’m sure they did not test all os/fs combinations either).

The reason I mention this is when Android came out, all the providers were backed by SQL. That crop of engineers had already forgotten how to read/write files. Today workloads span multiple systems. Single CPU synchronization seems to be considered a solved problem.

I can guarantee that single cpu sync is not a solved problem, and many similar issues are present with multiple system software as well.. Some of my friends have spent their entire professional lives debugging others poorly ‘designed’ multi system setups..

And that’s without even considering the biggest stuff up people do with multi system software – security (or lack there of..).

A simple way to avoid such issues is to keep all of your state on the stack i.e. pass the state variables as arguments. If you need state on the heap protect it with a synchronized block. When I see code examples like the one above, I think to my self that this guy or gale is an idiot.

I have far to many years experience fixing other peoples code. Concurrency should always be in the forefront of your mind while writing any thing.

And don’t get me started with NodeJS developers who think it is always single threaded, it’s not. Any time you make a call to a file or network resource bad things can happen.

Does ingle task OS/nanocomputer technolgy

have a solution of the data center electricity

consumption issues?

AI Overview

Yes, using specialized, energy-efficient

hardware, such as single-board computers

(SBCs) or systems with specialized

processors designed for specific

tasks, can contribute to significant

data center electricity savings. The

efficiency gains stem from several

factors:

Specialized Hardware for Efficiency

…

Nano Computers/Single-Board

Computers (SBCs):

…

n-Device AI:

…

Software and OS Optimization

…

Optimized Code:

…

Resource Management:

…

Overall Impact

Implementing these technologies

doesn’t solve the entire data

center electricity consumption

problem alone, as cooling and

power distribution also consume

significant energy. However,

adopting energy-efficient

hardware and specialized

systems is a key strategy

industry leaders are using to

maximize performance within

existing power limits and lower

operational costs.