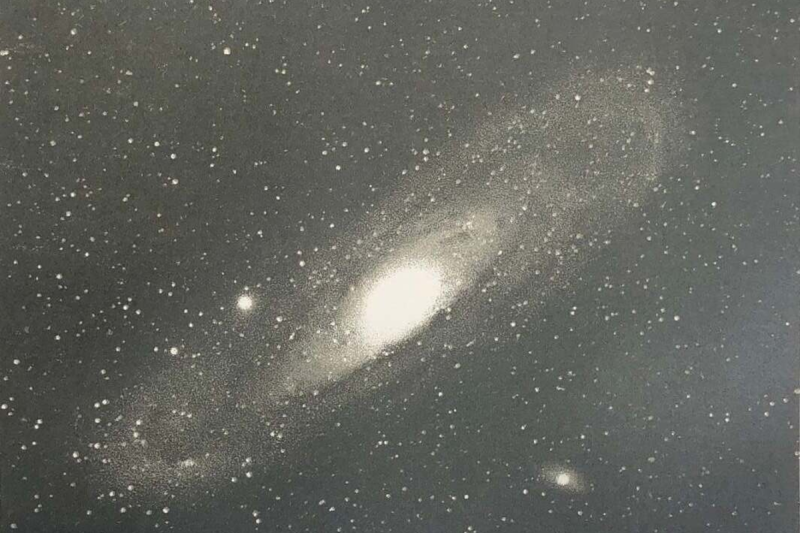

Space telescopes are all the rage, and rightfully so. The images they take are spectacular, and they’ve greatly increased what we know about the universe. Surely, any picture taken of, say, the Andromeda galaxy before space telescopes would be little more than a smudge compared to modern photos, right? Maybe not.

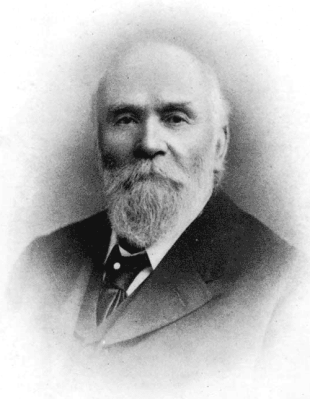

One of the most famous pictures of our galactic neighbor was taken in — no kidding — 1888. The astronomer/photographer was Isaac Roberts, a Welsh engineer with a keen interest in astrophotography. Around 1878, he began using a 180 mm refracting telescope for observations, and in 1883, he began taking photographs.

He was so pleased with the results that he ordered a reflecting telescope with a 510 mm first-surface mirror and built an observatory around it in 1885. Photography and optics back then weren’t what they are now, so adding more mirrors to the setup made it more challenging to take pictures. Roberts instead mounted the photographic plates directly at the prime focus of the mirror.

Andromeda

Because it took hours to capture good images, he developed techniques to keep the camera moving in sync with the telescope to track objects in the night sky. On December 29th, 1888 he used his 510 mm scope to take a long exposure of Andromeda (or M31, if you prefer). His photos showed the galaxy had a spiral structure, which was news in 1888.

Of course, it’s not as good as the Hubble’s shots. In all fairness, though, the Hubble’s is hard to appreciate without the interactive zoom tool. And 100 years of technological progress separate the two.

Roberts also invented a machine that could engrave stellar positions on copper plates. The Science Museum in London has the telescope in its collection.

Your Turn

Roberts did a great job with very modest equipment. These days, at least half of astrophotography is in post-processing, which you can learn. Want time on a big telescope? Consider taking an online class. You might not match the James Webb or the Hubble, but neither did Roberts, yet we still look at his plates with admiration.

What’s the craziest is that when Roberts took this picture, the true nature of what he was looking at – another galaxy, just like the Milky Way – was not truly understood yet. It was not until 1924, when Hubble put together Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s discovery about the relation of the period of Cepheid variables and their luminosity that the true scale of the universe became clear to humanity. Our current worldview is a mere 100 years old, who knows what lies ahead.

Did you forget to attach the pictures Roberts took?!

We did! It’s there now.

Some 170 years ago we finally learned how to inexpensively make large amounts of steel. Is your current car body made of shit steel or bicycle frame built with steel tubes that much different from what was possible in Belle Epoque?

No

It’s still the same Fe element with up to 2% C.

Think hower you want but the bitter truth is our science has probably peaked (logarithmic growth) and we’re stuck here until we die. Even Mars trip is a fallacy because in terms of absorbed radiation two way trip would be equal to standing inside Chernobyl reactor just after it exploded.

Also, where is your 10000000000 GHz CPU as promised by Intel when they were tryharding with Pentium 4? It didn’t happen and we’re still stuck with in an era where humbe 3 GHz E8400 is not that different from modern multi-core extreme CPUs for true gamer nerds. Both can play MP3, show webpages and write text documents.

“Roberts did a great job with very modest equipment. ”

Not modest in the least. Having put the huge “sensor” at the prime focus of a then-enormous scope, and self-invented astro tracking would put this at the cutting edge for the time and would be an enviable private/student telescope today (minus the film plates and clockwork, of course).

An article all about the images he took… And not a single image that he took in the article?

I get that I can browse away and look them up, but that seems like an odd editorial choice…

Well I can’t delete my comment so I’ll add an acknowledgement that you’ve added one now!

Back then it was relatively easy: zero light pollution.

It doesn’t sound easy to me, but at least he didn’t have to go to a remote mountaintop to find a clear sky. How many of the objects in his late-eighteenth-century catalog could Messier see over Paris today?

Yeah lack of light pollution helps, but to say that single factor makes it easy is… Not accurate. Lol. As the comment by Thinkerer pointed out, he was doing cutting edge work for his time. This was extremely challenging, and it’s why the pictures are so notable.

Space telescopes tend to be narrow-aperture for extreme magnification, to take maximum advantage of the lack of an atmosphere. This means it takes hundreds of exposures stitched together (generally with a computer) to make a single image of Andromeda, which is a dim but very large sky object. You may still also need time exposures, even though modern digital sensors are much more sensitive than old film. But traditional film techniques with short focus wide-field scopes can take the whole image in one go, onto a sheet of film with enough silver crystals to equal the resolution of hundreds of narrow digital images. Of course the scope is still mounted on a moving world, a problem Roberts solved, with an atmosphere which can only be mitigated by looking for a high place with calm weather. In any case the advantages of wide field scopes are being rediscovered; the ability to take large exposures quickly is what you need for planet hunting, where you’re looking at light curves of thousands of objects over months or years. Kepler (RIP) and Tess are designed for this, but their single mission purpose doesn’t command the big budges, large mirrors, and heavy lifters needed to make them compete in other ways with Hubble.