When thinking of home computers and their portable kin it’s easy to assume that all of them provided BASIC as their interpreter, but for a while APL also played a role. The most quaint APL portable system here might be the Ampere WS-1, called the BIG.APL. Released in Japan in November of 1985, it was a very modern Motorola M68000-based portable with fascinating styling and many expansion options. Yet amidst an onslaught of BASIC-based microcomputers and IBM’s slow retreat out of the APL-based luggables market with its IBM 5110, an APL-only portable in 1985 was a daring choice.

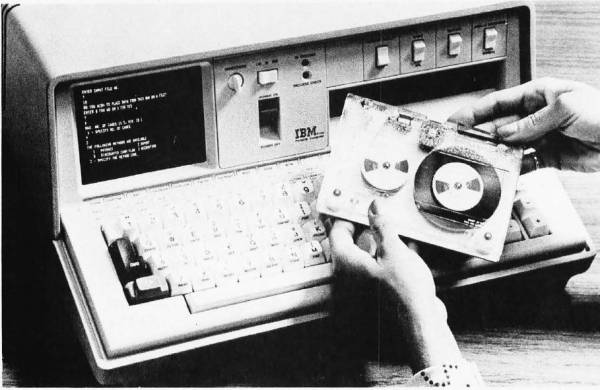

Rather than offering both APL and BASIC as IBM’s offerings had, the WS-1 offered only APL, with a custom operating system (called Big.DOS) which also provided a limited a form of multi-tasking involving a back- and foreground task. Running off rechargeable NiCd batteries it could power the system for eight hours, including the 25 x 80 character LCD screen and the built-in microcassette storage.

Although never released in the US, it was sold in Japan, Australia and the UK, as can be seen from the advertisements on the above linked Computer Ads from the Past article. Clearly the WS-1 never made that much of a splash, but its manufacturer seems to be still around today, which implies that it wasn’t a total bust. You also got to admit that the design is very unique, which is one of the reasons why this system has become a collector’s item today.