When a consumer electronics device is sold in the US, especially if it has a wireless aspect, it must be tested for compliance with FCC regulations and the test results filed with the FCC (see preparing your product for FCC testing). These documents are then made available online for all to see in the Office of Engineering and Technology (OET) Laboratory Equipment Authorization System (EAS). In fact, it’s this publishing in this and other FCC databases that has led to many leaks about new product releases, some of which we’ve covered, and others we’ve been privileged enough to know about before the filings but whose breaking was forced when the documents were filed, like the Raspberry Pi 3. It turns out that there are a lot of useful things that can be accomplished by poring over FCC filings, and we’ll explore some of them.

The first thing to know is how to get to the EAS tool. If you search, you need to search for FCC OET EAS (as FCC EAS is the Emergency Alert System. Thank you FCC for all your helpful TLAs). Or just head directly to the FCC OET EAS. Now that you’re there, you’ll see lots of search fields. The first four rows are probably all you ever need. Every company that registers with the FCC will get a grantee code, which is a unique 3 or 5 digit code that represents the company. Any product they register gets its own product code. Simple enough.

If you don’t know either (any product that you’re holding in your hand that has an FCC ID is required to put it on the packaging and on the device and in the user manual), just enter in the name of the company in the applicant name and you’ll likely find what you are seeking. The date range is helpful for limiting the results, but also enables another fun option. Just enter today’s date in the from-to fields and you’ll have a list of all the paperwork filed today. This is how the leaks happen. As soon as it’s listed, helpful people will see it and report it.

If you don’t know either (any product that you’re holding in your hand that has an FCC ID is required to put it on the packaging and on the device and in the user manual), just enter in the name of the company in the applicant name and you’ll likely find what you are seeking. The date range is helpful for limiting the results, but also enables another fun option. Just enter today’s date in the from-to fields and you’ll have a list of all the paperwork filed today. This is how the leaks happen. As soon as it’s listed, helpful people will see it and report it.

For fun, let’s look up something that’s near and dear to us; the Raspberry Pi 3. Search for Raspberry Pi in the applicant name and there are a few entries, some dated from 2016, and some from 2014. The 2016 ones are clearly the Pi 3, and their only difference appears to be the frequency range; it’s unclear why there are three separate filings.

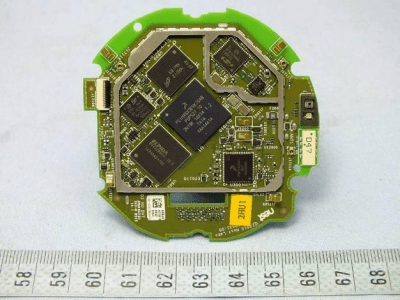

On any of them, we can look at the detailed information of the filing. This gives us all kinds of goodies, including the external and internal photos, user manual, and testing data. The photos are extremely important for finding motivation, as they will include pictures underneath shields for wireless modules. This lets you look at a product and determine exactly what is inside, which technologies they used, how they laid out the components, etc., and it’s all free and easily available as soon as it’s filed, which is usually before the product is even available for sale. Is there a product you like and you want to find out how they did it? Check the FCC database. Want to do a teardown of some competition without buying their product? Here it is!

The Raspberry Pi results aren’t a great example for this because you can already see what’s on the circuit board, so search instead for something like Fitbit or Nest. The internal photos document for the Nest device is 10 pages of detailed images of everything inside! This is very much a wealth of information for learning how the pros do product development. Some companies will obscure the chip labels in the photos, making it a little more difficult to figure out what’s inside.

Probably the least exciting but still useful thing is the test report itself. This is probably 90% boilerplate that is identical in every product, but it will tell you which frequencies it uses, and give you an idea of how strongly it outputs signals. That’s about it. Go back to the photos and user manual for all the good stuff.

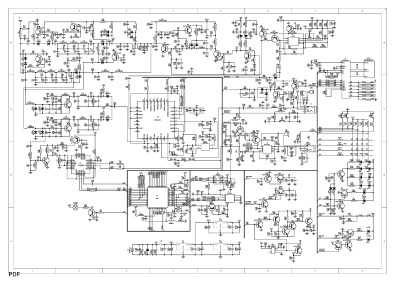

Every FCC filing contains a lot of documents, and it’s possible to request permanent confidentiality on some of them. This means that you submit the documents, ask that some of them stay confidential, and those will not be listed on the web site. Some of the documents can’t be confidential, like the user manual, test report, and internal and external photos, but others can, like the Block Diagram, Operation Description, Parts List (BOM), and Schematics. Not everyone files this confidentiality request, so sometimes, if you’re very lucky, you can get a lot more information about a product than you thought possible. For example, do a search for Grantee ZP5 and Product Code BF-82. They didn’t file the confidentiality letter for this particular product (but they did for others), so you can see everything, including schematics showing the part numbers!

If you are preparing your own product for FCC testing, find a couple products you like and see what they did for their documents so you can save yourself some time preparing similar documents. There’s no reason not to! If you want to learn how a particular design challenge was solved, or get the inside scoop on hardware before the release date, FCC EAS is a great place to begin.

[main image source, iPhone 6s FCC ID BCG‑E2946A]

Thanks for the reminder…. I used to do this all the time a decade plus ago, don’t know why I forgot about it, possibly an intermediate website update that made it painful to use or something.

All I get is: You are not authorized to access this page.

And you woder how chinese clones come to market so fast.

Well mainly because before you even FCC test it, you order the chips from china and the beta boards from china….

+1 yep

You can ask for many things to stay confidential. Not every manufacturer cares though, usually thinking the product will be yesterdays news before someone made the clone.

I thought User Manuals couldn’t be confidential. Sony filed with FCC ID AK8MEXN4200BT and all but the test report, RF Exposure report, Label location, and a few letters (confidentiality and PoA letters) are not listed. Apparently the rules have been changed and the only information mandatory to be listed as public is the RF Exposure and the report. Even int/external photos are confidential with this listing. This may be the exception, not the rule, but it IS possible to hide almost everything.

AFAIK you can have some of these confidential for a “protection” period.

180 days from equipment grant.

Also, not everything will be the same FCC company ID (eg, the first 3/5 may be different), and not everything is made by the company that’s on the tin.

As a double-also, some equipment might not be on there for reasons. I give two examples:

1: Globalstar’s Sat-Fi product has two FCC-licensed modules connected to it with no actual engineering on Globalstar’s part — so the only FCC docs you can get are the modules individually.

2: ViaSat’s Exede modems are covered under the authorization for the entire satellite service license itself so there’s no FCC data available for the Surfbeam or older modems. The newest WiFi modem is on there, however.

Quicker search here:

https://fccid.io/

http://fccid.io and a smartphone is a great tool if you’re in a big box store and wondering how hackable an RF gadget is. The box often has an FCC ID on the outside, or should be visible on the product.

Especially useful when cruising the clearance aisle for spotting BLE fitness trackers and keyfinders that have the nRF51 SoC. Those can always be wiped and programmed with a normal SWD debugger even if the code protect bit is set.

Hi usually use it to check the specifications of new devices.