On a bright spring morning in 1940, the Royal Air Force pilot was in the fight of his life. Strapped into his brand new Supermarine Spitfire, he was locked in mortal combat with a Luftwaffe pilot over the English Channel in the opening days of the Battle of Britain. The Spitfire was behind the Messerschmitt and almost within range to unleash a deadly barrage of rounds from the four eight Browning machine guns in the leading edges of the elliptical wings. With the German plane just below the centerline of the gunsight’s crosshairs, the British pilot pushed the Spit’s lollipop stick forward to dive slightly and rake his rounds across the Bf-109. He felt the tug of the harness on his shoulders keeping him in his seat as the nimble fighter pulled a negative-g dive, and he lined up the fatal shot.

But the powerful V-12 Merlin engine sputtered, black smoke trailing along the fuselage as the engine cut out. Without power, the young pilot watched in horror as the three-bladed propeller wound to a stop. With the cold Channel waters looming in his windscreen, there was no time to restart the engine. The pilot bailed out in the nick of time, watching his beautiful plane cartwheel into the water as he floated down to join it, wondering what had just happened.

Although the story is made up, the engineering problem facing the RAF was all too real. Early in the Battle of Britain, the now-legendary Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, powerplant for not only the Spitfire but also the Hawker Hurricane and the Lancaster bomber, was having a serious problem. RAF Spitfire pilots reported that the fighter would lose power during negative-g maneuvers, meaning that a simple jinking move to line up a shot on an enemy pilot or a quick dive to get out of the line of fire could stall the engine. Sometimes the power loss was momentary, but too often, the engine would just die in flight and fail to restart.

Like all good pilots, the young RAF flight officers quickly adapted to the shortcoming of their new fighters. They learned to do a half-roll before diving, to avoid a negative-g attitude and keep the Merlin running. It worked, but it was a stopgap at best, and a potentially deadly restriction on the ability to maneuver when it mattered most. What’s worse, the Luftwaffe pilots were quick to notice the problem — it was hard not to notice the black smoke and loss of power, even in the midst of a dogfight — and they capitalized on the enemy fighter’s weakness. Something had to be done, lest the tide of the Battle of Britain turn against the RAF.

Fatal Flooding

In many ways, the Spitfire and the Hurricane were planes built around an engine. While the airframe of the Spitfire, with its beautifully elliptical wings and sleek lines, was certainly revolutionary, it was the mighty Merlin that made the plane what it was. The liquid-cooled, supercharged engine was powerful, simple, and reliable, but the choice of carburetors over fuel injection would come back to haunt the engine’s designers.

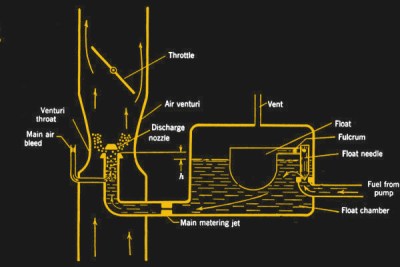

The carbs used in the Merlin were much the same as any carb found on a lawnmower or older car today: fuel was metered into a bowl by a simple float valve before being sucked into the intake airstream under suction provided by the Venturi effect. In straight and level flight, the carbs worked fine. But in a negative-g situation, fuel was forced to the top of the float chamber away from the jet, cutting off the flow of fuel and causing the engine to lose power. Returning to a positive-g attitude, fuel sloshed back into the float chamber and flooded into the jets, providing an over-rich fuel mixture to the cylinders. Raw fuel entered the exhaust manifold, where it burned and produced the sooty black exhaust. In the “right” situations, enough fuel would enter the supercharger to flood it, stalling the engine altogether and preventing it from restarting.

The obvious solution was to replace the float-bowl carbs with pressure carbs. But with the Battle of Britain raging, taking planes out of service for engine overhauls was not sensible. The RAF needed a quick fix until a more permanent solution could be fielded.

Miss Shilling Saves the Day

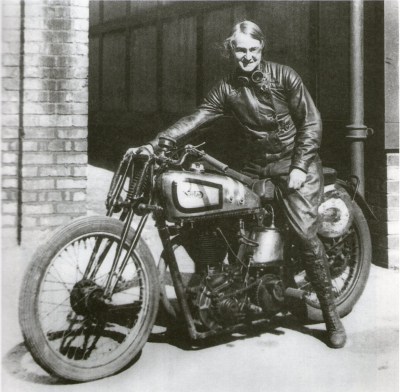

The fix that eventually saved the Merlin came in the unlikely personage of Miss Beatrice Shilling. In a time of strict social conventions and well-defined roles, Beatrice, who went by Tilly, broke all the rules. Fascinated by engineering since she was a teenage girl taking apart motorcycles and racing them, Tilly bucked convention, earning a degree in electrical engineering in 1932 as one of only two women in her class. She followed that up with an MSc in mechanical engineering the next year.

While racing motorcycles competitively — she won awards and set records in 1934 on a 500cc Norton bike to which she had added a supercharger, clocking a 106 mph lap — she started working at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in Farnborough. There, in the opening days of World War II, she specialized in aircraft carburetors.

While Rolls-Royce worked on new carb designs for the Merlin, Tilly came up with a fix for the RAF’s woes, and like many such solutions, it was deceptively simple. She reasoned that restricting the fuel flow to the carburetor bowl would prevent flooding, so she designed a simple brass disc with a small hole in it. She calculated the dimensions of the disc to allow just enough fuel for maximum power. As a bonus, the device could be added to the planes quickly and easily, without removing the planes from service.

Officially, the device became known as the “RAE Restrictor,” but as Tilly Shilling toured RAF bases to oversee the installation of the device, the rough and ready aircrews had other ideas. “Miss Shilling’s Orifice” became the new name of the life-saving brass disc, which once installed in the fuel lines solved the problem. The Spitfires were back in the fight, and the RAF eventually pushed the Luftwaffe back across the Channel, thanks in no small part to Tilly Shilling.

Tilly’s Legacy

Tilly did not rest on her laurels. With her workaround in place, she returned to the RAE and continued work on improved carburetor designs. She continued working for the RAE until she retired in 1969, making contributions to fields as diverse as rocket designs and braking aircraft on wet runways. Switching from motorcycles to cars of her own design, she also continued racing well into her 60s alongside her husband George Naylor, a fellow engineer and later RAF bomber pilot whom she married in 1938 on the condition that he first post a 100-MPH lap on a motorcycle.

Beatrice Shilling was a larger than life figure who deserved the many honors bestowed upon her, including the Order of the British Empire and a pub in Farnborough named after her. But being the engineer who fixed the Spitfire and turned the tide for the RAF was probably her proudest achievement.

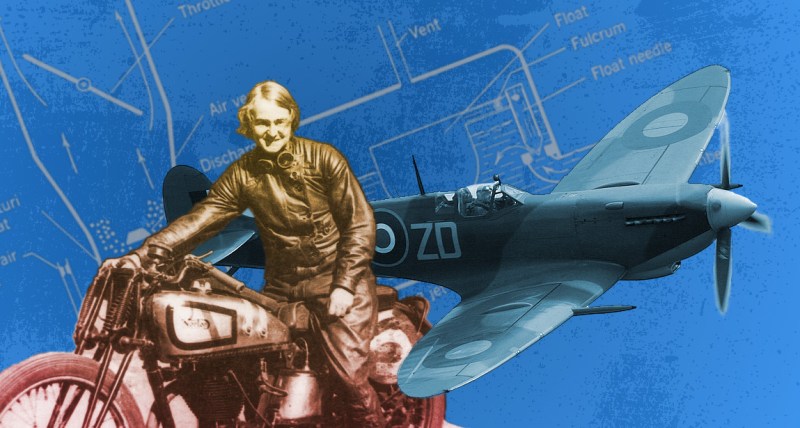

Sources for Main Image:

- Beatrice Shilling via Vintage Norton Motorcycles

- Spitfire GNU/GFDL by Franck Cabrol

- Carburetor diagram via EngineHistory.org

A brilliant solution indeed. Gotta love the name the air crews gave it.

I wish Tilly Shilling was my grandma.

I didn’t know my grandma and grandpa’s roles in the war until I had sat down and talked to them about it many years ago. They were pretty “kick-ass” for their day. Would never have brought it up if I hadn’t asked though.

I bet Tilly didn’t bring it up to her grandkids either.

I’m less concerned about kicking ass during a war and more excited that she was a very smart engineer who liked to build motorcycles and race them. I’m sure her grandkids knew about that.

I was dumb enough not to ask my grandparents about the war, but now it’s too late to fix that. Found out at my grandpa’s funerals how once, he was buried alive by a German tank while he was rolling between the tank’s tracks and the tank was swirling above trying to crush him. He managed to escape unharmed. Some other incredible war stories were told that night, after a few of his former comrades got drunk and start remembering and talking between them haw it was back then, during the war, then later how the world got crazy again, this time with the Communists, and so on.

Your grandma or grandpa might have been like Miss Shilling, too, just talk to them while they are still around.

None of my grandparents were action heroes. But they were awesome in their own ways.

You all know in today’s world a name like “Miss Shilling’s Orifice” wouldn’t fly. (Pun intended).

Sexual assault is hilarious

That’s a high quality pun, and far cry from a sexual assault.

Trivializing real sexual assault by calling “everything” sexual assault is NOT hilarious.

Offensive? Disrespectful? Vulgar? May be.

Sexual assault? NEVER.

And yet the Salem witch trials continue unabated.

Yes but they had a thing called a sense of humor back then. I ‘ll bet She laughed her butt off when she first heard it.

“While the airframe of the Spitfire, with its beautifully elliptical wings and sleek lines, was certainly revolutionary,”

It wasn’t revolutionary at all, it was evolutionary. Elliptical wings were nothing new at the time, the Spitfire was built using traditional aviation design techniques and institutional knowledge.

Revolutionary design came with the P-51 Mustang which was the first aircraft built with a laminar flow airfoil which is why it’s wings look so distinctly different from any other aircraft at the time. It was also one of the reasons why it was so much better than anything else in the air.

The P51 was the first aircraft designed to have laminar flow wings, but the first aircraft to actually have laminar flow wings was the consolidated B24 liberator, they just didn’t know it at the time.

My favourite part of the P51 story is the fact that the prototype was produced in 117 days, when you consider how little we knew at the time and how adaptable that airframe was and how impressive the the aircraft turned out to be, that really brings home the dedication of the designers.

All this with carburettors that needed a hack!

Not quite correct. The P51’s airfoil was designed to be laminar flow but in reality it wasn’t. The B24’s Davis airfoil was not laminar flow either, it was optimised for a high lift to drag ratio in the flight envelope bombers operated in. It definitely is not laminar flow.

The P51’s real edge was its (comparatively) very low drag cooling system, a fact that was not recognised at the time when it was assumed that the wing profile was the key. Other fighters accepted cooling drag as a necessary evil and compensated with more power and less weight wherever possible. E.G. Tempest, p47 etc.

The P-51 was also a Merlin power aircraft, it was originally fitted with an Allison engine. The RAF found the performance was poor at high altitude and tried it with the Merlin and found it to be a superb aircraft. Luckily the Merlin was already being made in the USA under licence by Packard for the Warhawk or Kittyhawk/Tomahawk as it was known in Europe.

It wasnt better that anything else in the air…the german me 262 was far superior…thankfully the germans didnt have enough of them

Not according to the fellows that flew against them, and later flew them in flight tests. In one of Yeager’s books he talks about the P-51 vs the Me-262 and how much better the P-51 was and why. I would think he should know as he sure shot down a number of them and later got to fly the 262 after the war. The Germans had plenty of aircraft, what they ran very low on, was pilots. Yeager talked about that as well. A lot of the pilots he came up against had very few flight hours and almost 0 time in combat flying. Andy Anderson and Bob Hoover talked a lot about this as well.

My understanding is the big problem with the ME-262 was the engines and the fact they were very short lived and unreliable. Apparently, the Germans had not yet developed the material science needed to make the metal parts inside withstand the high temperatures. Therefore the engines could only last 20-25 hours of operation before needing to be replaced or rebuilt. So, while it may have been a good performer while it was actually flying, it probably spent more time on the ground being serviced than it did in the air. And it was probably much more costly for them to maintain as well.

The Mustang had a much better range than the Spitfire, but other than that it was either equal or worse than it. For example the rate of climb was much worse (about 3000 ft/min vs 5000). See http://www.spitfireperformance.com/spit14afdu.html for a contemporary comparison.

If we compare the latest and greatest of each line, the P-51H has a climb rate of 4500ft/min at 1600ft vs the Spitfire MkXIV’s 5040ft/min at 2000ft. RoC is a nice metric when comparing fighters in an Interceptor Role, what the Spitfire excelled at, but it’s less important than other metrics in other roles. The Mustang was easily 20-50mph faster flying level at all altitudes, maintained this higher speed when encumbered with external pods. The Mustang had a longer range which made it hands down the best aircraft in the Bomber Escort Role.

Did you read the link? No, the Mustang wasn’t any quicker unless you were comparing against early marks. The Mustang is quoted as having a top speed of 440mph at 25,000 feet. A mk XIV Spitfire would top out at 449mph and the mk 24 at 454mph at similar altitudes. The later marks of Spitfire were powered by the significantly more powerful Griffon engine (delivering about 2100hp).

The Mustang was a much better bomber escort, with a far greater range than the Spitfire. The Spitfire was a better interceptor and could turn tighter, which gave it the edge as a fighter.

Respect!

“four Browning machine guns” – make that eight, four per wing.

But 30 cal, so total is like 1 BMG 50. (Bullets must have been about 1/5 the mass of the 50.)

Try 3/5th the diameter of a .50 cal and probably close to that as far as mass goes.

8-.30s could ruin your day real quick

11.275 grams versus 45.

So that would mean that eight 0.3 in (7.7 mm) is approx. equal to two 0.5 in (12.7 mm). However the rate of fire of 0.3 in (7.7 mm) was probably higher so …

The energy (10,00+ foot-pounds versus maybe 2200) and ability to carry high explosive, incendiary, and armor piercing rounds of significant size. A P-47 had eight 50 BMG. I’m just saying a couple 50’s on a Spitfire would have been spectacular. And the ballistic coefficient for the BMG ammo was very good.

I agree that 0.5 in / 12.7 mm would have been much better Spitfire weapon early in the war.

According to the RAF it took on average neary 5000 rounds for a spitfire to bring down an enemy aircraft, so I’m with you guys, .50s would have been better, not sure if this takes into acount aircraft fitted with the hispano cannon, whih was a 20mm affair, if it does, either RAF pilots are shit shots or it’s way more difficult to bring down an aircraft than I imagine.

5000 rounds (including hits and misses) is almost certainly for Spitfire I, armed with only rifle-calibre machine guns. Hispano cannons probably only needed few hits to destroy enemy fighter for example.

The plane in the photo has a 4 bladed prop and I don’t see 8 MG’s on the wings!

(as long as we’re being picky B^)

There were something like 24 marks of the Spitfire, and some had four-bladed props. The Spit in the featured image looks like it might be a Mark IXc with 20mm Hispano cannon. Deadly.

Indeed, as is mentioned in Public Service Broadcasting’s excellent track ‘Spitfiire’:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_u4Md_aXVJE

Rats, got that wrong. I read that early Spits had only four guns mounted, and figured 1940 still counted as early. Turns out they were fielding eight guns by 1938.

Corrected in text. Thanks for picking that up.

Thank you for this interesting article. Everyone makes mistakes, we are all human.

here’s a video of it happening, https://youtu.be/YzRlga2-Hho?t=47s

That was pure gold!

It all started like a good movie, I almost felt the g dive, then going into technical details, then… nobody saw it coming. We ended up canceling the 8 PM meeting because people was keep bursting into laughs.

Here here, bravo!

Heh, I’ve said it before, the only thing decent with Norton branding on it ran on Petrol not Windows.

About 35 years ago, I saw a Norton that had its transmission case welded back together. It looked like nothing larger than pieces no larger than 2×3 inches were what they had to weld.

Another great article and insight into not overcomplicating a solution.

Another great article and insight into not making a solution over-complicated.

Miss Beatrice sounds wonderful, but I want the supercharged Norton!!!

Bravo!

Please keep these coming.

I lived in a village in the 90s where you’d often see a Spitfire overhead… never realised how lucky I was for that until much later. https://charfield.org/charfield-spitfire

I live and work in a village about 20 miles from biggin hill and there’s a two seater spitfire based there that can be hired for £2500 for half an hour, apparently there are a truck load of rich people in the Uk because it flies over this area a dozen time a day in the summer.

it is a truly awesome sight, especially when the passenger is a bit brave, you really can’t appreciate the noise of a merlin until a spitfire barrel rolls over head at what looks and feels like less than 1000 ft

Anyone supercharging a 500cc Norton has massive balls.

Especially at the age of 60!

One of “only” 2 women in her class? That’s hardly exceptional even today.

Another long and detailed article about her:

https://www.damninteresting.com/how-miss-shillings-orifice-helped-win-the-war/

Quite an error in your article. Without going into the complications of the Merlin’s fuel system and how long a cut would last, if a piston aero engine cuts the propeller will only stop rotating (as opposed to producing thrust) if the airspeed is close to zero. Under all other conditions the prop will be driven by the airflow and as soon as the reason for the cut is removed, will start without any help from the pilot. In general zero airspeed will only happen in a stall turn which is very unlikely in combat. I

I understand that Miss Shilling was the first female Member of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Incidentally, my University (Loughborough) ran engineering courses with several female students around 1919.