In the late nineteenth century, there was only one Earthly frontier left to discover: the North Pole. Many men had died or gone insane trying to reach 90°N, which, unlike the solidly continental South Pole, hides within a shifting polar sea.

One of history’s most driven Pole-seekers, Robert Peary, shocked the world when he announced that his wife Josephine would accompany him on his expedition to Greenland. The world responded, saying that she, a Washington socialite with no specialized training, had absolutely no business going there. But if it weren’t for Jo’s contributions, Robert would probably have never made it to the Pole, or even out of Greenland. Sewing and cooking skills may not seem like much, but they are vital for surviving in the Arctic climate. She also hunted, and managed the group’s Inuit employees.

Josephine Peary was more than just the woman behind the man. An Arctic explorer in her own right, she spent three winters and eight summers on the harsh and unforgiving frontier. Back at home, her Arctic accounts painted a picture of a frozen and far-off world that most could only wonder about. Jo’s writing career brought in expedition money for her husband, which sometimes turned into bailout money.

Woman About Washington

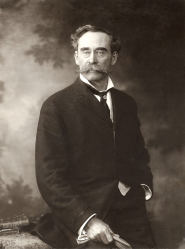

Josephine Cecilia Diebitsch was born May 22nd, 1863 to German immigrant parents who encouraged her to explore the world. Her father, Hermann, was a linguist at the Smithsonian Institute. Because of his position, the Diebitsch family rubbed elbows with much of high society. Though Jo was raised to be a Victorian lady and upheld those values, she had progressive ideas about what women could do with themselves in addition to being wives and mothers.

After graduating from Spencerian Business School in 1880 as valedictorian, fluent in French and German, Josephine was being groomed to follow in her father’s footsteps. Then she met Robert Peary at a dance.

A Man, A Plan, A Canal, Nicaragua

Robert Peary was a civil engineer for the Navy. Shortly after meeting Josephine, he was assigned to Nicaragua to survey land for an ill-fated canal that was eventually cut through Panama instead. Prior to this trip, he was shopping for a sun hat in a men’s clothing store. He got to talking with the clerk, Matthew Henson, who told Peary that he had several years of seafaring experience as a cabin boy. Peary hired him as his personal valet on the spot.

Henson became indispensable to Peary as his field assistant and ‘first man’. Peary took him to Nicaragua with him, the first of many trips the two would take together. In Nicaragua, Peary began to dream of being the one to discover the North Pole.

All the while, Robert kept up his courtship with Josephine through six years of far-flung naval assignments, and they were married in 1888.

From the Social Circle to the Arctic Circle

Robert was determined to reach the North Pole, and Jo used her network to secure funding for an expedition to Greenland in 1891. At that time, no one outside of Greenland knew yet whether it was an island, or a solid landmass that stretched across the Arctic.

Robert revealed to reporters that Josephine would be joining him on this expedition, which was a completely scandalous idea at the time. First of all, there were scores of men, actual men, who couldn’t hack it in the Arctic. Second, she was a woman and no non-native woman had ever been that far north.

The gang — Robert, Josephine, Matthew Henson, and a small crew — left Brooklyn on June 6th, 1891 aboard a seal-hunting ship destined for Greenland. A month into the voyage, they encountered icy waters on the approach into Greenland. The ship’s tiller abruptly spun around, striking Peary in the lower leg and breaking both bones. For the next six months, Robert recuperated in the small shared cabin with Josephine at his side.

In the meantime, Josephine and the crew hunted, learned the lay of the land and introduced themselves to the Inuit. Robert hired native families to help with the expedition, assigning the men as hunters and guides, and the women to sewing fur suits. The two groups became friends, and shared meals in the frigid evenings.

Jo herself set up fox traps, shot deer with a Colt .38, and speared the occasional narwhal. Once, when the boat was surrounded by angry walruses trying to leap aboard, she hunkered down in the boat, reloading rifles as fast as the men could empty them.

When they got back from Greenland, both Pearys were in demand. Robert had discovered Independence Fjord, which offered conclusive proof of Greenland’s islandhood. Reporters of all stripes pressed Josephine for Artic housekeeping tips. In 1894, she published My Arctic Journal, a vivid narrative about her experiences in the Arctic and life with the Inuit. This lively narrative showed a rambunctious, human side of the expedition that Robert’s dry prose did not.

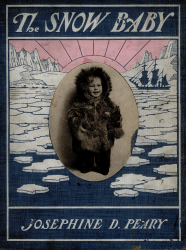

The Snow Baby

The newspapers had a field day when Josephine returned to the Arctic in 1893, eight months pregnant with their first child. Both she and Robert were publicly scrutinized for what reporters and physicians deemed a complete lack of parenting skills. Marie Ahnighito Peary was born just a few degrees away from the North Pole. Her middle name honors the Inuit woman who sewed her first fur suit.

To silence the haters, Josephine wrote a second book, The Snow Baby, about motherhood inside the Arctic circle. The slim, picture-rich book shows a happy and healthy child with bright, curious eyes. Marie was a delightful spectacle for the natives, who had never seen a white baby before.

The Snow Baby was a best-seller and brought in a tidy profit. Jo used much of the proceeds to fund her husband’s explorations, which included the occasional rescue ship.

An Iron Will

The second expedition hit a few snags after the Snow Baby was born. With dwindling food supplies and the only doctor out exploring the ice cap, Jo, baby Marie, and several other expedition members went back to the States.

She soon learned there would be no rescue ship sent after Robert. The sponsors expected him to suck it up and sail his cutter several hundred miles down the shore to Danish settlements. Jo took matters into her own hands, using her social pull in DC to raise the $10,000 necessary to charter a proper rescue ship. For comparison’s sake, that’s over $250,000 in 2019 money.

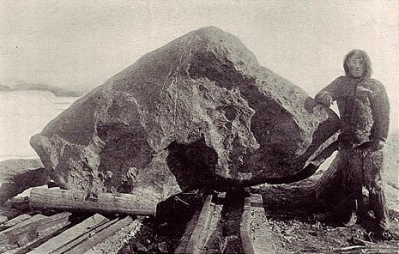

Robert brought two meteorites with him on board the rescue ship. These were fragments of what came to be known as the Cape York meteorite, which had struck Greenland some 10,000 years earlier. Its arrival planted the Inuit firmly within the Iron Age, and they cold-forged many tools from this iron-rich cosmic gift.

Peary had left a third fragment behind, which was the biggest of them all at 100 tons. All three Pearys and their crew returned to Greenland in 1897 to retrieve it. It is unclear whether Robert had permission to take these fragments. Some say that by the time he did, the Inuit were already trading for guns and may not have cared. The Pearys sold them to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where they can be seen today.

Rescue Mission Impossible

Robert took a five-year leave of absence from the Navy and sailed to Greenland again in 1898, dead-set on reaching the Pole. Jo stayed behind to look after Marie, and because she was pregnant again. Unfortunately, this baby didn’t live more than a few months.

Jo had sewn a taffeta United States flag for Robert to take on his journey. He used it well, wrapping himself in it against the icy wind, and planting pieces of it whenever he got further north than he had before.

When Jo got word that Robert had lost eight of his toes to frostbite, but had no intention of quitting, she packed up Marie and left for Greenland. But Robert wasn’t there. She eventually learned that he was living in Canada with a young Inuit mistress, and had fathered two sons with her. But before she could take off in the ship for the Great White North, ice had frozen it to the shore. Jo, Marie, and the crew were trapped for the winter.

On Top of the World

Robert finally made it down to the ship, and they reconciled. They welcomed Robert Jr. two years later, in 1903. Robert continued to seek the Pole while Jo stayed in the States to give lectures and raise the children.

On April 6th, 1909, Peary reported to the world that he and Matthew Hensen had reached the North Pole. He later revealed to Jo that he’d planted a diagonal slice of her flag there, in the crevice of a rock. Peary moved on from exploration and was promoted to Rear Admiral. He died in 1920 of pernicious anemia.

Though Robert’s name is more likely to appear in the history books, Jo had a lot to do with her husband’s successes. She was an Arctic explorer in her own right, and her colorful impressions of life at northern extremes educated and inspired as much as they delighted.

Thanks for the suggestion, [Nitpicker Smartyarse].

“She also hunted and managed the group’s Inuit employees.”

Perhaps this shocking sentence is missing a comma?

@Kristina Panos, thanks for the article!

Eats, shoots, and leaves.

Thanks.

No Jo, don’t forgive his adultery…

Perhaps she engaged in some, herself?

“introduced themselves to the Inuits”

Inuit is plural, Inuk is singular

Thanks for mentioning this, fixed!

I thought Mathew Henson had a lot to do with Peary’s success. At a time when black people were relegated to lesser roles, he was off on arctic expeditions.

I hope when Hackaday does a.series on “Forgotten Black peoole who made a difference” Henson will be included.

Michael

Mathey Henson was black? might have been worth actually mentioning in the story. As it is I was wondering “Who GAF about this Henson guy? Isn’t this a story about Josephine?”

I didn’t know about it until a National Geographic article in the early nineties. It was about Peary’s claim to the North Pole. But it had photos, and there he was. I’m sure I saw the issue with the daughter of a friend, who is black. So I’m not arguing against this entry (though I think other women are more noteworthy), but it almost seemed ironic to do this entry when Mathew Henson did more, but may be mostly invisible.

Michael

“He later revealed to Jo that he’d planted a diagonal slice of her flag there, in the crevice of a rock.”

So, the North Pole is an island…with rocks.

Yes I had thought the same thing – I need to do more research

“In The Noose of Laurels (1989), Herbert concluded that Peary had falsified some records and had never reached the North Pole, although he had been close”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wally_Herbert

Wasn’t Lady Franklin the first lady of the arctic?

She spomsored various expeditions to find the fate of her husband, which probably incidentally helped exploration.

Nice article. Please add an “after the break” after the intro so scrolling to the next article is faster

Peary first to the North Pole? Two words: Wally Herbert.

Two words: Santa Claus.

The right person in the right profession in the right place showing full dedication and honest professionalism to attain spectacular success. Another example of “The Right Stuff”.

I seriously enjoy these articles! Thank you. Please keep them coming!

This is a very sanitized article and misses many of the controversies of Peary’s life. For example it is almost certain he never reached the North pole and falsified data to show he did. He had a number of children with Inuit women. Now whether Josephine knew, condoned or was complicit in any of these is up to debate, but it is important that the wide story is known, otherwise it reads like a Victorian melodrama

IIRC, a photo taken at the North Pole was later analyzed. (In the 1980’s?) and the direction and placement of the shadows indicated the photo was taken at (or very close to) the North Pole.

There is no doubt that Robert Peary was a great arctic explorer. However inconsistencies in his diary, the lack of verifiable proof and character flaws in the man himself casts doubt on his claim. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

The camera claims are not enough. His original camera does not exist, so its focal length cannot be verified nor can the times that the images were taken. Either of these are enough to put a huge error margin in the position. Even the analysis cannot be said to be independent.

Maybe he did reach the pole, but there is enough doubt that such claims should be tempered in articles like these

The article is about Josephine’s remarkable supportive contribution to an expedition her husband attempted and perhaps botched a bit, but that is on him, not her. Clearly she made a remarkable contribution towards the endeavor and did so with distinction without regard to whether or not he botched it.

We are told that Peary brought a meteor to New York, but not that in 1897 he brought six Greenlanders to New York, as objects of research and curious sights. Five of them died and were exhibited at a museum where the boy Minik later saw his father’s skeleton.

GREAT book about spending five winter months alone operating a meteorological station, Advance Base, and nearly dying alone in the dark at the other pole: “Alone” by Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

Thanks for your article. If folks would like more info, I have published on Josephine Peary at:

Homemaking, Snowbabies, and the Search for the North Pole (in “North by Degree: New Perspectives on Arctic Exploration,” Lightning Rod Press, American Philosophical Society).

Josephine Diebitsch Peary, Journal Arctic, March 2009

-Patricia Erikson