When we go to the cinema and see a film in 2022, it’s very unlikely that what we’re seeing will in fact be a film. Instead of large reels of transparent film fed through a projector, we’ll be watching the output of a high-quality digital projector. The advantages for the cinema industry in terms of easier distribution and consistent quality are obvious. There was a period in the 1990s though when theatres still had film projectors, but digital technology was starting to edge in for the sound. [Nava Whiteford] has found some 35mm trailer film from the 1990s, and analysed the Dolby Digital sound information from it.

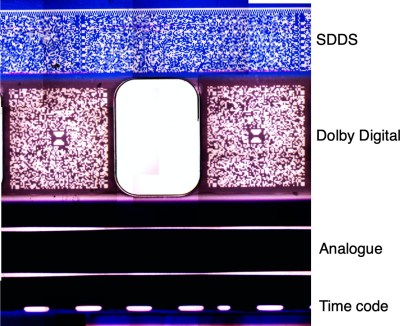

The film is an interesting exercise in backward compatibility, with every part of it outside the picture used to encode information. There is the analogue sound track and two digital formats, but what we’re interested in are the Dolby Digital packets. These are encoded as patterns superficially similar to a QR code in the space between the sprocket holes.

The film is an interesting exercise in backward compatibility, with every part of it outside the picture used to encode information. There is the analogue sound track and two digital formats, but what we’re interested in are the Dolby Digital packets. These are encoded as patterns superficially similar to a QR code in the space between the sprocket holes.

Looking at the patent he found that they were using Reed-Solomon error correction, making it relatively easy to decode. The patent makes for fascinating reading, as it details how the data was read using early-1990s technology with each line being scanned by a linear CCD, before detailing the signal processing steps followed to retrieve the audio data. If you remember your first experience of Dolby cinema sound three decades ago, now you know how the system worked.

The film featured also had an analogue soundtrack, and if you’d like to know how they worked, we’ve got you covered!

Dolby lobby.

Where’s the open source?

Open source != free /l ibre FLOSS software

Also where it is? I see AV1 being very alive and healthy as a royalty free video encoding scheme, opposing stuff like HEVC and h266.

Just propose a better audio codec and rallye the industrie for your goals. The features a movie theater requires might be much more than your average 5.1 or 7.1 home cinema.

AVS, is probably worth mentioning. I still find it hard to believe that it has its own patent pool. And the AVS3 blurb is totalitarian not creepy at all “… more efficient coding tools for performance improvement and especial for surveillance videos and screen content videos are being developed in the second phase of AVS3”

“Just propose a better audio codec”

AC3’s been unencumbered by patents for over 5 years now (which… I’m pretty certain this is) and of course buckets of AC3 decoders are out there. I think the only thing that’s not commonly available is a decode of the actual matrix, but patents for that should have expired as well.

It amazes me that stuff like this ever worked.

“Some hacked-together things never leave the house/workshop/basement, and others travel the world.”–[EGO]

Wonder what the processing delay was? There had to be a few frames of difference between the audio that Dolby needed to send out and the picture in the frame.

No doubt the alignment of the sound track was shifted slightly in relation to the picture so by the time the sound came out, it was in perfect sync or close enough.

You could configure the frame delay for the audio. An auditorium on my college campus (which still in 2022 occasionally does show movies on film!) has 2 beautiful Norelco DP-70 projectors from the 1960s, which were retrofitted with Dolby Digital sound readers. In the documentation for the rack mount Dolby processor (Which received SDI video from the camera sensors mounted in the reader heads) it described how to calculate and set this offset.

Basically no processing delay. But there was another delay: the picture is not next to its corresponding sound. The digital sound pickup was placed after the image projecting. So for the image and the sound to line up, the sound must be a number of frames (10-20? Can’t remember) ahead of the image.

You’ll be surprised to see there are still delays in very large theatres. Because of the physics. Sound travels at 343m/s in air. In a large room, the time it takes for the sound to travel from the screen to the back of the room is about 1 or 2 frames (at 24 fps). At 343m/s and 24fps, 1 frame is 14.29 meters ! :D

The analog-only projectors had the same “frame shift”, where the optical reader for the analog audio was in a separate assembly from the gate (underneath). The print needed to move smoothly through that assembly, unlike the gate, where it advanced one frame at a time. If your “loops” were too tight the audio would warble. Stereo prints worked perfectly in projectors with a mono audio reader, since it just averaged the two tracks. Those commercial cinema projectors were amazing machines… nearly bulletproof. I was a projectionist back in the ’80’s for a drive-in, and our equipment was really old. The only failure I ever saw was a blown rectifier for the lamp housing (ours still used carbon arc rods at the time).

Good thought, but the processing delay is less significant then accounting for where the optical scanner (“reader”) is located, relative to the picture. The digital audio blocks are placed early enough that the reader can even be placed *below* the picture gate, at the bottom of the film projector.

There is an adjustable delay setting in the Cinema Processor to allow for the reader to be placed anywhere, including on top of the projector (requiring a loooong delay).

Thanks for the insight.

Hah, would have been surprised if you hadn’t been here Del ! Anyway, the alignment marks in the corners are a cross-multiplied Barker-code. This has a high enough correlation peak that pixel (fixel) centres can be located at around 0.1 feature size. The DD in the centre was included as a safety precaution – there were concerns that this would be a high-wear part of the film because of the shape of the sprocket-drive system. The original matrix was 76×76, not sure if it morphed to 78×78, possibly covered by the patents (which make interesting reading) including US Patent 5,757,465. I trust the statute of limitations is up on this one :) -Mark

There’s actually a third digital format there, not just two. The “timecode” track is the DTS metadata stream. For DTS, the audio recordings for the movie were shipped on one or two CDs (or DVDs, I can’t remember … the 90s were a while ago), and the timecode contained the data needed to find and sync the audio.

It was CD’s. We had a rack mounted ‘player’ that had 3 CD drives that you’d put the discs in. We still have all of our old film equipment sitting around collecting dust.

Film is pretty cool. If you keep it long enough, it’ll become vintage again!

I was kinda sad when my university’s film house got rid of their film projectors. I understand why, i can only imagine the cost of a film print these days…

I know a guy who has a full size 35mm movie projector (and a handful of films) in his living room. But that’s a bit too committed to film to my tastes!

Semi-relevant aside:

I had the distinct pleasure of internet-knowing Mr. Seagrave who featured prominently in the development of the system (as evidenced by the linked patent). He was equally brilliant, kind and humble. I got to test out a later product that he was developing (outside of Dolby Labs). Unfortunately, he’s no longer with us.

How do you know Charles ? He was a lovely guy to work with…

I became acquainted with him through a website (essentially an offbeat discussion forum) where he was known as “csea”. I once made a website themed trinket and traded with other members for whatever they wanted to trade. I got a FWI CD from him in exchange. (Since you knew him, you’ll undoubtedly know of FWI.)

I enjoyed several email conversations over the course of, I guess, a few years. One memorable discussion revolved around whether it was ironic, or appropriate, or foreshadowing for a sailor with a sea-faring lineage to have the surname “Seagrave”.

He once shipped me a system to try out that he was developing. It visualized sound nodes in a space to optimize home theater setup.

He seemed like an interesting man. I wish I’d known him in real life.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGU3ZzXTxmc that pulls some heart-strings seeing him again; he was just a lovely, generous person, and talented engineer. My last memory of him was the look of shock on his face when I resigned from the firm, and handed him a pile of master-keys for the building that we worked in – I had no right to have them (and never abused the privilege). I think we share five patents; all are referenced from my resume/CV on my ‘website’ below.

Yes, LASSIE was the system. I looked once to see if it carried on after him, but didn’t find any evidence. It was really interesting to actually see the behavior of sound in my living room.

Some of my website compatriots met him at a gathering and confirmed that the person did indeed match the impression I had formed.

Good times.

A smart technology indeed. The only sad part was that the encoded audio, although containing 6 channels (5.1), was about the quality of an mp3, requiring to filter out sub frequencies and anything above 10kHz before the Dolby digital encoding (to avoid horrific parasites from the encoding process). It was very frustrating after months of work on a soundtrack. The passage to DCP finally allowed the use of full 24bit 48kHz AES audio channels, for which there was no available space on film. On certain mixes the backup audio on film (the actual analog track, which was only Dolby SR -ie 4.1 the back channel being mono, so Left Right Center Back-) actually sounded better than the « mp3 » encoded Dolby digital packets…

I’m new to all this! I just learned that Dolby Digital sound is physically printed between the sprockets of film. I understand how DD sound is synchronized with the image frame. Do you know why the sprocket gap doesn’t create an audible silence?

In other words, I’d like to know how the physical gap of the sprocket is compensated for in terms of elapsed time it takes for the gap in sound information to travel in the projector. Does information from the previous DD code cover the sprocket gap distance to meet the next DD code? Do the DD codes on either side of the sprocket gap meet virtually in the middle of the gap when the digital sound bits are assembled?

Maybe the answer is obvious, but my brain can’t understand the practical aspect of synchronizing analog and digital.

If you know the answer, I appreciate it.

You understand correctly.

Each block of DD data contains enough audio information that it takes 1/(24*4) = ~10.4 milliseconds to “play” the audio in that block. By the time the audio in that block has been “played” the next block has been decoded, creating another 10.4 mSec of audio.

Another way to illustrate continuance of audio is to imagine a series of blocks of data dumping into memory, while a steady stream flows out the other end. In other words, enough data was buffered ahead, to allow the steady output stream.