For those outside the world of education, it can be hard to judge the impact that ChatGPT has had on homework assignments. If you didn’t know, the first challenge of the 2023 Hackaday Prize is focused on improving education. [Devadath P R] decided that the best way to help teachers and teaching culture was to confront them head-on with our new reality by building the homework machine.

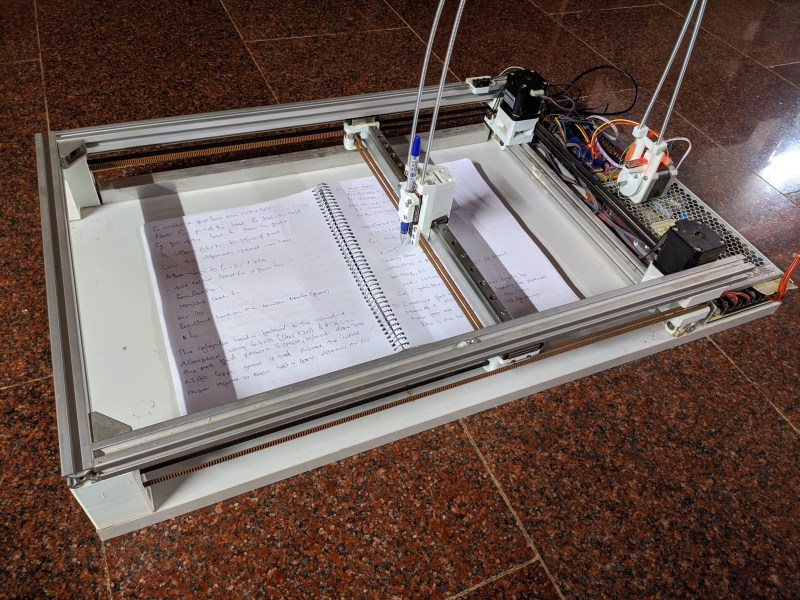

The goal of the machine is to be able to stick in any worksheet or assignment and have it write out the answers in your own handwriting, and so far, the results are pretty impressive. There are already pen holder tools for 3D printers, but they often have a few drawbacks. Existing tools often take quite a while to generate G-Code for long pages of text. Hobby servos to lift the pen up and down take more wear than you’d expect as a single page has thousands of actuations. Vibrations are also a problem as they are a dead giveaway that the text was not human-written. [Devadath] created a small Python GUI to record their particular handwriting style on a graphics tablet and used ChatGPT to generate answers.

Multiple versions of each character are used, though [Devadath] plans on slightly varying the strokes as needed to create variation. A hand-rolled Python script outputs G-Code with page turns include, which makes it easy to dump multi-page content in. The core XY CNC pen plotter glides on linear rails, runs on Klipper firmware with vibration cancellation, and has an actuator driven by a stepper for longevity. To [Devadath]’s credit, they have been using this setup since 2022, and teachers haven’t noticed so far. They say the plan to open-source the code and design for the plotter once they’re finished iterating.

It demonstrates AI’s capabilities and what can be built with parts on hand. Whether it pushes education away from rote memorization remains to be seen.

The following statements in your article are an example of a misguided project that does harm to the student and his education. I fail to see how this helps a teacher. Rather, this project lets a student avoid doing home work and thus deprives him of learning. A better help would be to expose uses of AI by the student and hold them accountable.

… decided that the best way to help teachers and teaching culture was to confront them head-on with our new reality by building the homework machine.

The goal of the machine is to be able to stick in any worksheet or assignment and have it write out the answers in your own handwriting,

I think you may be missing the point they’re making.

How do you help a locksmith? You show them how to pick their lock.

I think you’re missing the point here – the purpose of teaching is not to provide the teacher with homework, but for the student to learn. Sure, this is an issue for exams and assessed coursework, but for most homework this is only cheating the student who skips the studying.

And the purpose of homework is to make sure that the student has at least seen the material. Our courses are built in a way that you have to return enough homework or you don’t get to take the exam. Teachers who don’t do this see people just skip the lectures and homework, study at the last moment and bounce the exam multiple times until they finally get enough points by trial and error to barely pass – and that’s a waste of everyone’s time.

A related problem is that since you need some sort of a degree almost for serving coffee these days, many students just take the path of least resistance. This means people either drop out, or just take the bachelor’s and go do something entirely different with their lives, and we have to lower standards to keep to the quotas to get students and make them pass. This is especially a problem for the first year mass courses that are mandatory for all, where some teachers just choose a “write your name for pass” approach. We still require them to learn, but it’s really beginning to resemble spoon-feeding adult children.

So if the students are allowed to do the homework by automation, and pass the tests by copy/pasting from the textbook in an online exam, we’ve arrived at the Soviet System: the system pretends to educate the people and the people pretend to be studying. Everything works on paper and yet the economy keeps tanking.

“A related problem is that since you need some sort of a degree almost for serving coffee these days, many students just take the path of least resistance.”

Some are getting away from that.

https://www.cio.com/article/472345/the-4-year-debate-do-degree-requirements-still-matter-for-it.html

A big reset.

https://www.hbs.edu/managing-the-future-of-work/Documents/research/emerging_degree_reset_020922.pdf

Yep. One Certification Salad coming right up.

It’s an even bigger scam, because you can buy a bunch of do-nothing certificates that only require you to complete the online course. I have several, all required for legal or insurance reasons at some point. The training instructor tells you the answers to the multiple choice exam, because everyone who paid for the training course has to pass.

In this case, the purpose is exactly to educate the teacher (not the pupil!) about AI, and so the “best way to help teachers and teaching culture was to confront them head-on with our new reality by building the homework machine”

Except the person is trying to get out of copying lab reports without the teacher noticing that they’re machine copies.

I have a feeling that building the machine was a far more valuable learning experience than any worksheet that could be sent home.

Worksheets =/= Learning

Memorizing facts isn’t learning yet, but facts are the foundations of forming ideas in your head.

Suppose you forgot what a nail or a screw is, then someone asks you to design a wooden fence. How would you do it? Glue?

That’s a great question! I’d have to go do some experiments to find out for myself!

Not that it can’t be done, but the solution would be more convoluted, like lashing it together with rope. Point is, it would take you more time to research your options and figure out (again) that nails and screws exist, which makes your task that much harder.

When you have the simple stuff already down to memory, you can skip ahead to the bigger problems rather than re-inventing the wheel every time.

Woe is the kid whose parent complains, “Why are you teaching my son multiplication tables, what a waste of time, he’s got a calculator!”

He will be left with impaired numeracy.

“How would you do it?”

Stick welder.

Actually not impossible:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0k04hjdYuQ

Thanks @dude for finally showing me where that window shutter gif meme came from

Maybe using a lattice or coppicing.

>Suppose you forgot what a nail or a screw is, then someone asks you to design a wooden fence. How would you do it? Glue?

Google. Then screws, probably.

The big problems start when you know so little that you can’t even search for it. You may not even know that entire categories exist, or you remember things entirely wrong and confabulate information. “What’s that thing that puts things together… quickeners?”

If I selectively forgot that screws and nails exist, but I truly understood the concepts, I might invent them by thinking that ramming a dowel into an oversized hole would pin it together, then realizing i could probably even force it to make its own hole if it was thin and hard, or maybe if it had a shape that could drill its way into the wood and even provide clamping force. Of course, without the fact that nails and screws are cheap and easy, I might first think to use wire/rope or to shape the boards to interlock.

I think the number of facts you’ve encountered and thought about matters a lot more than the fraction you memorized. If you memorize 13 fasteners, on a test you score better if you were only exposed to 15 than if you were exposed to 30. But if you were exposed to 30, you might have learned why fine threads work great for steel and poorly for wood, or maybe being exposed to lockwire helps you remember to think about the direction you wrap wires around a screw terminal. If you set up a memorization test you want most people to pass without test prep taking up an undue fraction of their time, you might make the test cover very few fasteners, which seems unhelpful to their future. I’m not sure if I think it would work to just set expectations lower – what do you think?

>If I selectively forgot that screws and nails exist, but I truly understood the concepts

Question is, is it possible to fully understand the concept if you lack some of the most basic examples of it? That to me sounds like a learned party trick, where you can perform something without understanding what you’re doing.

Of course memorizing minor variations of a theme isn’t productive. You don’t need to learn the entire 10×10 multiplication table by rote memory either – it’s more efficient to learn only the ones that are hard or “special” and just solve the easy ones like 3×5 each time.

I think if you’ve never been exposed to the most basic examples, that would make it tough to have learned how they can work. Even then maybe you came from a different background where it’s lashing that’s basic and screws are rare, but you still learned enough to understand a screw when someone shows it to you. It’d definitely be worth learning about screws and nails, but once you have, you don’t necessarily need to continue to remember them at all times if you instead just remember how they work.

… It occurs to me that for many people, whatever prototypical examples they have of screws are probably how they retrieve screw related memories that they don’t have a separate example for. So it’s possible that for those people, forgetting screws would also mean forgetting how they work at the same time. You’ve made me realize that someone might have a hard time accessing their memory of without thinking of screws if they weren’t really familiar with any other screw-like-things e.g. bolts.

Still, for less basic things I tend to repeatedly “invent” things that already exist. Sometimes I knew they existed and forgot, sometimes I never heard of them before. I think there’s room for forgetting most of the examples of anything you’ve heard of, except for the “special” / unique ones like you said, if the ones you do remember give you a good idea of the possibilities.

Students have been looking for ways around homework as long as there has been homework :-)

I think you should consider this, as the developer intended, like a piece of art. It’s asking the observer to think about something. In this case the impact that AI tools are going to have on education.

Probably millions of students aren’t going to go out and replicate this build. But – no doubt – millions of students are already looking at AI as a way to get their schoolwork done faster…

“millions of students are already looking at AI as a way to get their schoolwork done faster…”

I hope that isn’t the case as the student then hasn’t learned anything. Sounds like we are well on the way to idiocracy . Well, maybe we are partially already there with what you see in the news any more. AI (as defined today) could be a real threat to society in general if you look down the road. Time to get out the books, and get down to plain o’ reading, writing, and arithmetic… without a computer in sight.

Yeah, wrong your hands and clutch your pearls, that’s productive.

Wring**

My daughter wrote a movie review for Humanities class a couple of weeks ago.

The instructor thought it was crafted beyond her skill level, and asked if she’d used ChatGPT to write the review instead.

I dunno about misguided…

Education in the US has a lot of problems, with no creative solutions being proposed in the past 50 years that have worked.

As proof-of-concept, this machine might jumpstart people into thinking more deeply about what an education is, what it is we want (for our children) out of an education, and how to conduct the education process.

Well people are certainly doing the asking.

https://www.reddit.com/r/ArtificialInteligence/comments/133c3wh/the_implications_of_advanced_ai_will_we_still/

Maybe at best it will be that assistant we wished for when going through school.

The goal of the project is to make a post-homework world tangible. To take it from a shadowy idea from the news to a physical object you can look at and think about.

For teachers, trying to stay relevant, helpful, and even motivated is a struggle in the current world, and this is meant to help them get a grasp on how to move forward. Put simply, this is art. It does nothing technically new, it arguably is less useful than standard chatgpt, and it isn’t economical or marketable. All it is, is a physical representation of the chinese room.

It’s kinda like sabotaging the economy to make the post-capitalist world tangible… yes, but do you really want it?

in which case im curious to hear your thought about schools that don’t give any homework to start with. also where do you draw the line? how about students who are fast typer but have a bad penmanship?

In my experience, the student with bad penmanship, who takes time to write down the answers, who is concise and to the point because they can’t write long paragraphs, gets better results than the student who can quickly type the answer down and then soon forget it.

Students often use verbosity to mask the lack of detailed understanding.

If anybody is stupid enough to use this, they’ll bounce sooner or later. We already saw that after the lockdown: cheaters got caught with their pants down because they just couldn’t complete the in-person written exams. Passive learning by cramming youtube videos doesn’t work because hardly any of the details actually stick – welcome back next year.

Well having a GOOD example really helps.

https://youtu.be/NlYXqRG7lus

Still, retention of facts takes time and repetition. Watching a video once only gives you the broad strokes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forgetting_curve

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Overlearning

Human brains actively delete information which is deemed “unimportant” because it isn’t repeated often enough.

I’d say the ones who copied from their materials (or AI) were doing rote memorization, but doing it badly – skipping the memorization part using copy-paste instead of reading and then writing. The ones who used AI to write their essay were just cheating.

Multiple choice tests aren’t ideal, but interestingly when they are beyond what someone can cram for, you begin to see a real separation in grades between the people who can reason out an answer and the people who are just good at remembering things and avoiding mistakes in following procedures – both valuable things, but not the most valuable in my opinion.

Short format questions with unambiguous answers tend to help those who can be prompted to recall a procedure rather than just facts, and can implement that procedure even if they do it blindly. That sort of person may be tricked by a similar sounding question to what they memorized, but will get decent grades without full understanding.

Short and long essay questions used to try to make sure someone could speak confidently about a topic, whether they knew what they were talking about or not – but at least when it was just humans, it was harder to write well about things they didn’t understand. Humans can add fluff to an essay to reach the necessary length, but usually they don’t add any more on-topic detail – just more length and maybe some digressions. So you can still establish what someone understands that way, and if they say something incorrect, they probably didn’t understand that thing. AI makes understanding harder to distinguish, because their result will have acceptable grammar and structure, but may or may not show whether someone actually understood it or if their AI was able to find enough similar writing to fake it. I once asked an AI to write about thermionic converters, which are similar to vacuum tubes except they are meant to just convert externally applied heat into electricity. Even after manually correcting it, the AI insisted that they work by using electricity to produce heat to produce electricity. To a human grader, perpetual motion machines clearly indicate complete and total lack of understanding. If the AI had remained vague enough to avoid saying the wrong thing, it might have been able to make a vague answer with enough correct parts to get partial credit for the question.

>Humans can add fluff to an essay to reach the necessary length, but usually they don’t add any more on-topic detail

Students who don’t understand the topic act similarly to ChatGPT by being vague and giving you apparent detail without committing to anything. For example, “A house may be large or small, it may be constructed of various materials including wood or stone, metals, ceramics and plastics. It is usually located close to people in cities or towns…”

Notice how the text can refer to just about anything if you blank out the word “house”. A statue can have the same description, or a swimming pool. What they’re doing is writing a “horoscope” and hoping the recipient is polite enough to interpret it in their favor.

Yeah, agreed. Though students also tend to learn to avoid making strong claims about things they’re not sure about in case it’s false. ChatGPT might include mention of houses made of straw or sticks or bricks due to the childrens’ story. A student might not include straw and would rephrase sticks to wood or something more generic, in order to manage risk. (Since omitting a potential rare material is a minor problem, but adding something incorrect is a major one.)

Humans fail versus ChatGPT when ChatGPT can mimic the way people normally write about a topic, while the students decide to be just as vague but can’t avoid writing with a different pattern. Kind of like if a student wrote a horoscope-type answer describing a creature and the student was picturing a housecat while the actual creature was very different. The line “Some people think they’re cute when they look up at you wanting food” is acceptable for a lot of animals, but it would be out of place in an essay about a sabertooth cat. The AI would probably know that they’re usually mentioned as being scary and not make that mistake, but then it’s luck whether it accidentally claims they have six toes.

So when you see something obviously wrong, you can still take lots of points off for it, but if the AI builds up the same length of horoscope-type answer without chancing to make such a mistake, then the essay question doesn’t show you the difference in students and AI very well.

I think it’s more an indictment of the necessity of after school work. Homework is dumb. Do the assignments in class.

Maybe good when the idea of participatory families still existed.

Classes are often too short to start and finish a topic in one sitting; it takes a certain amount of time to just start and stop. In K12, the “projects” are better than the homework. A daily worksheet with a long series of similar problems brute forces the learning process; if the kids are forced to spend 2 hours a day on the topic of course they’ll remember more than if they only spent 30 effective minutes. But not everything is about practice, and people tend to get into the habit of thinking it’s normal to assign enough work that some kids don’t have time for anything else.

The US primary education system is mostly designed around the least common denominator, because we qualify it by passing rates for standardized testing. Filling out worksheets for rote memorization doesn’t do anything for a fair number of people. It’s just a waste of time if you already know the material / actually pay attention in class. I would place good money on the student that built a machine to do their homework has better scores than many that fill in the worksheet by hand.

>It’s just a waste of time if you already know the material / actually pay attention in class

And how do you do that? Especially for people who aren’t interested or motivated to learn what you have to teach them, because they’re basically stupid kids?

I love hackaday just a hack a day ago yall posted an article about laser triangulation on 3 d prints. you think you could use that to detect the AI forgery? https://hackaday.com/2023/05/06/laser-triangulation-makes-3d-printer-pressure-advance-tuning-easier/

dont have to go that far.

anyone experienced in handwriting analysis or with the slightest understanding of penstroke will identify these as machine produced. The pen maintains perpendicularity with the surface. Needs a few more axis of motion and a lot more training

Well… if you are able to make a homework machine (design and build it yourself) you’ve proven your worthy of a degree.

Or just proven you can follow instructions.

Which can be an asset depending on the career you’re aiming at.

>Whether it pushes education away from rote memorization remains to be seen.

Should it?

Passive learning really doesn’t work. We saw that during the lockdown when people were just consuming youtube videos and answering online questionnaires and puzzles. Once we got back to normal written exams, people did so poorly almost nobody passed – because they only had the vaguest superficial idea and were used to copying all the rest directly from the materials without thinking about it. The simple fact that you have to spend effort to read a text or listen to a lecture and then write it down – by hand, not just copy-typing it – seems to have much better results.

Human behavior arises out of internalized information interacting with the external world. When you remember nothing, there’s not much you can think about, and there won’t be those “a-ha” moments where something clicks in your head to solve a problem.

Also as an interesting aside, people who started before covid retained good results either way, while people who only saw online education completely folded when they had to produce answers on the spot.

And it wasn’t just the failure to come up with an answer – they were producing wrong and nonsensical answers to questions they were previously able to complete correctly.

I think once you pass the low hurdle of being able to do anything at all in a subject is when rote memorization begins to become a problem. Much like the old apprentice/journeyman/master delineations, rote memorization of facts followed by procedures is a starting point. No matter how good you are at that, you don’t understand anything until you’re able to figure out things you don’t already remember, or adapt to things that don’t match what you have seen before. That’s when things start to click. And if you’re someone who’s made it to that stage but you’re tested on rote memorization ability, then you’re being let down by your educators.

I agree that you should spend time reading and writing about a topic if no other means of review presents itself, but posing and answering questions, or thinking through variations on a situation, or other things that go beyond repetition can be crucial. If you’re taught about physics using a car rolling down a slope, and you ask yourself what happens if the wheels are different sizes, then you find out the answer, you might learn something. If you work out the same problem twice? Not as much, but better than plugging numbers into formulas you stole off the internet.

It will re-surface when you’re doing the more advanced stuff that requires mastery of the lower levels. It would be a bummer if you’re doing some mathematical analysis and you find that you’ve forgotten the chain rule of derivation for example.

Well, you’ll master some things as you go. But improving your mastery of other low level things isn’t worth hindering your progress at learning the advanced stuff, yet that’s the choice I was faced with when I was in school. And most of the time, learning what’s possible and how to think about a situation will be more likely to lead you to the right answer than being very good at knowing exactly how to perform any particular operation. You should remember the chain rule by understanding it rather than memorizing it if you need it at all, since it’s unlike a lot of the derivative rules which just say what the derivative of a certain class of functions is. But I wouldn’t necessarily prioritize being good at knowing derivatives without a chart or calculator, if it means giving up e.g. knowing you can go from considering a perimeter to considering the surface it encloses (green’s theorum).

>Whether it pushes education away from rote memorization remains to be seen.

Should it?

Passive learning really doesn’t work. We saw that during the /censored word/ when people were just consuming youtube videos and answering online questionnaires and puzzles. Once we got back to normal written exams, people did so poorly almost nobody passed – because they only had the vaguest superficial idea and were used to copying all the rest directly from the materials without thinking about it. The simple fact that you have to spend effort to read a text or listen to a lecture and then write it down – by hand, not just copy-typing it – seems to have much better results.

Human behavior arises out of internalized information interacting with the external world. When you remember nothing, there’s not much you can think about, and there won’t be those “a-ha” moments where something clicks in your head to solve a problem.

This.

During medical school and pharmacology in particular, everyone was trading their big lists of meds and action and side effects and so on. Then try to memorize that.

I made my own, line by excruciating line and by the time it was done, didn’t actually need the list itself much. Making the list WAS the education.

Same with anatomy- sure look in a book but if you really want to learn it, like 3D relationships and such, drawing them yourself is way better. Mastery.

Separate debate if, say, a dermatologist needs to do this at all but …

In a similar way, it’s interesting to work with project managers in engineering, where you may have to explain the same technical detail (and why it means their idea doesn’t work) multiple times because they keep forgetting the details and going back to “But what if we just…!”

Had a prof who would let anyone bring in a single side of paper “cheat sheet” with anything on it. Same logic — if you write it down, you learn it. And the act of picking what goes on the limited sheet space teaches you what’s important. Etc.

All in all, I thought it was pretty cool.

And it’s realistic in jobs in many fields to refer to at least a cheat sheet worth of material from time to time, so in studying for any of those fields it makes sense to allow a small amount of the same. That way you’re able to focus on understanding instead of remembering equations or irrelevant precise facts.

The reason why you require people to remember is to make them remember that the fact exists even if they can’t remember what it was, so they know to look it up in the cheat sheet.

Looking back on teaching high school in the 2000’s, I recall only a few students who use cursive. I’m sure that producing their typical scratching works the same. I would not mind doing the writing in my notebooks.

Cursive only really works well with fountain pens. For ballpoints and mechanical pencils that need a certain amount of pressure, it’s more difficult to maintain a good continuous line.

True, it was developed for fountain pens and I much prefer them for writing of all sorts for the very low fatigue – if you know how to write with a relaxed hand and arm off the table. But todays kids, and the ones I was teaching in the 2000’s writing is torture. There were never taught to do it well and apparently all developed their own ball-of-knuckles death-grip auto-cramp methods. It was actually painfull to watch.

A good ballpoint is OK and some of the Pentel family have a fiber nib in the shape of a fountain pen nib and they work very well.

My handwriting is terrible and I get the “yips” often where I just randomly draw some extra curve and then have to go back and erase it, but give me a smooth piece of paper and a fine marker, and suddenly it just works.

I like fountain pens, especially as I can just refill them from an ink bottle, but there’s a massive difference in the cheap pens every business seems to buy and something like my 0.25mm pentel slicci, which takes very minimal force and controls its ink somewhat better. It helps a lot in trying to read my writing too, if the lines are suddenly possible to tell apart and I’m not fighting the pen.

The answer is to pay teachers more to teach concrete practical activities evaluated in class time with smaller class numbers. The financial savings model of mass “education ” by handing out creative /reflective writing challenges is what is going to be challenged. Why not now write an AI homework marking machine, and we call sit back and relax.

The current lack of true educational values, ie a strong personal relationship of the teacher and student(s) together, leaves the current model exposed by AI. My first year Physics unit had 3 of 1 hr lectures and a 3hrs practical session each week. Our practical work was designed to be very educational and the work had to be completed and written up within the three hours. Our books never left the lab with us. This must have annoyed the hell off boarding college kids who had a network of wet jelly intelligence support in the form of off campus tutors to make sure the little darlings got through. It was a lot fairer to the poor kids who could not afford such live in advantages. It levelled the playing turf a good bit. The Physics lab was looking for gifted honest students, not cheats or fakes that did not do the hard yards themselves. By comparison Chemistry practicals were written up externally as was rife with “assisted” write ups.

The answer to AI distorting education? Plan better more meaningful education. The rote learning educator and the institutions that make vast sums of money from this brittle facade is what is being exposed here.

I look forward to being able to pass off the onerous task of weeding out the bullshit in Hackaday replies by using AI, especially the replies written by AI. Now that would be handy.

In the US education is entirely in the hands of “Professional Educators” at the teacher’s colleges, and the unions. The last 20 years has been the disaster of “Group Cooperative Activities” and “circular curriculum” in which say a math book sparsely covers a lot of topics and comes full circle maybe later in the year and covers them a little more deeply. Then next year in “Math 2” you start the circle again, and again in “Math 3”. Basically most of the kids never figure out why they did that goofy matrix multiply thing in Math2 that somehow produced the answer to a bugs and frogs and trees question. Or the problem with which bicycle to make in your factory by drawing some lines on paper, or that it was a geometric approach to linear programming. The American student today is very ill served by the public schools.

Maybe this will force a change for the good but I will lay odds against.

Textbooks are a well known scam that’s been around forever; many university professors who don’t write their own or know of a good free reference will just specify something dated that looks useful while being more affordable. At the K12 level, I know the review process sucks and mostly the schools buy whatever’s available from the usual suspects whenever they get the money for a refresh.

The individual teachers are basically herded into doing whatever new thing they are told they have to do if they’re going to keep trying to teach, sometimes. And sometimes, they don’t understand it either. :/

They buy whatever is being bought by the Texas schools. It drives the market. Home schoolers have much better choices, like Saxon for math.

There used to be teachers and researchers separately, but nowadays with the funding cuts there’s teacher-researchers and the teaching is allocated with just 20-30% of the total funds and about 10% of the total time because it’s the research that pulls in money from outside funding sources.

There are still tenure track research positions. They often require teaching one class for one semester a year. But the problem remains of the constant demand to find more grant money and employ more grad students with said grant money. Writing grant applications and papers to submit to publications leaves little time for research. The academic world is rather badly broken.

The problem isn’t new. In 1908 Felix Klein published a series of papers on elementary mathematics from an advanced standpoint. He wrote them for public school teachers. His concern was the extent to which new college students were both unprepared for the mathematics courses and unfamiliar with the notation and methods used by the experts. The teacher’s colleges and “professional educators” had gone off in their own direction using their own theories on how to teach the subject (highly influenced by the American John Dewey, whose ideas are still influential in US education departments). His goal in the ‘Erlangen Programme’ was to bring the teachers in line with the professional research mathematicians. There are excellent English language editions of the three volumes and well worth reading. “Elementary Mathematics from an Advanced Standpoint: Arithmetic, Algebra, Analysis”, “Elementary Mathematics from an Advanced Standpoint: Geometry”, “Elementary Mathematics from a Higher Standpoint: Volume III: Precision Mathematics and Approximation Mathematics”

The engineering industries could stand to teach a few engineering schools and especially the K12 schools the same lesson. And the field of business would love if K12 taught how to use a typical office suite on a desktop computer (at minimum).

im sure pearson is already drooling at the idea of having AI write the problems and answers for their online homework systems. then they will charge more money for the access because “AI powered”.

I remember a short story that focused on a teenager, morose because her father wouldn’t spring for the Latest Greatest Font upgrade for her “writer”, a dictation machine that transcribed her words into written form.

when I can buy it on aliexpress on tinde?

I’m a teacher, and I have taught in both the US and the UK.

I absolutely love and appreciate this as an artful response to the education system. I don’t think it’s likely to be terribly practical for anyone other than the inventor to use, but that’s not the point. This is a piece of mechanical rhetoric and performance art. It would have been way less work to just write the damn homework but this guy would rather do weeks of meaningful creative work than a few hours of rote copying. I love it.

One interesting thing — In the comments above, there seems to be a cultural disconnect happening due to the different approaches to homework between the US and the UK. In US secondary education (AKA high school) a percentage of your grade typically comes directly from completing homework assignments, often weekly. The exact details of this are left up to the teacher. In UK secondary education (GCSEs, A levels), homework pretty much only exists to help you prepare for an exam, and your final grade will be at least 70% from a standardized final exam. So cheating on homework, whether you approve of it or not, means very different things for the student in these different systems. (Don’t know about other countries. I think the UK approach is the more common one around the world?)

Unfortunately, I don’t think that innovations like AI chatbots or this homework writing machine are likely to make the education system in any country see the error of their ways and replace memorisation with authentic tasks and constructivist approaches. What is far more likely is that we will see even more reliance on timed exams under strict conditions. Timed exams are a great way to measure memorized knowledge and a very particular type of writing skill. Their other strength is that you can call them absolutely ‘fair’ in that everyone can be sitting the same exam with the same resources at the same exact time across the whole country. Unfortunately it is absolutely terrible at measuring problem solving, creativity, or research skills.

I don’t care how creative or good at problem solving and research you are if you lack the basic knowledge and even terminology of the subject because you’ve never memorized it. Thou shall not pass.

Re-inventing the wheel creatively is still wasted effort.

Comment glitched, but I think as bad as homework is, even timed exams are better. #345453534 has my full reply.

Even when homework (and quizzes, which are often similar) are a smaller fraction of your grade, things like chegg, tutors, and study groups regularly boost the final grades of those who use them above almost all of those classmates who don’t. The students who use such strategies have effectively seen their assignments completed before they’ve started it, along with a full explanation of the work, except that hopefully the specifics aren’t available and they can’t just copy the answers verbatim. It’s basically like having an older sibling who’s taken every class you take and gave you all their work, but they can’t take your test for you. Even then, if your test depends on a lot of cramming right before, well, if you had help you probably have more free time to study for the test.

Projects (even individual projects) tend to have grades that aren’t as skewed by the use of such strategies, but instead they are skewed by the fact that as a rigidly graded assignment, there are things you can’t do that you’d do if it was a project for a non-academic purpose. So if you can’t approach the end goal the way the instructor intended, you have to go above and beyond to figure out not only the lesson you were supposed to learn, but what it is that they intended you to do to get there, why it doesn’t work, and what to do instead that they will hopefully accept. If they instead set problems for you to try and address in a more-than-sufficient timeframe where everyone’s equally prepared and supplied, the fairness is a relief.

Multiple choice and such has its downsides, but just taking a timed exam is pretty good, and I think well designed questions can actually address creativity and problem solving, if there’s room for that in the topic under test. For example, you can definitely solve a programming puzzle like the ones on codingbat in a creative way. I used to often see how few lines I could use, or I’d use recursion for fun. Of course, it’s hard to test research like this. But you could provide a standard reference book for a few problems and make some of the problems be a short answer where the student says what the first few things they would look for in order to research X would be, or what sort of a question they could ask in order to get the answer. The instructor would have to grade how good of a question the student could formulate, though, using judgement.

Ugh, got the comment glitch again. #345453534