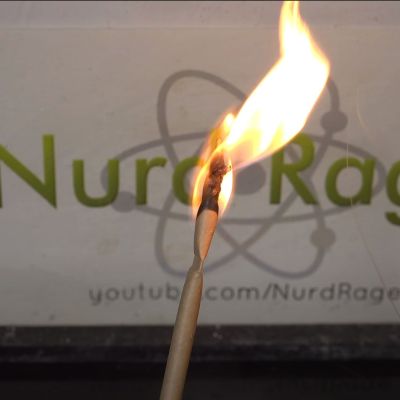

The history of making fire at will is a long and storied one, stretching back to the days when we’d rub wooden sticks together, or use flint and steel to ignite tinder. An easier, albeit vastly more expensive and dangerous alternative came in the 19th century when chemists discovered auto-ignition using a potassium chlorate mixture and sulfuric acid. This method was refined and later patented by Samuel Jones in 1828 as the ‘promethean match’ after the God of Fire, Prometheus, which is the topic of a recent [NurdRage] chemistry video.

Using practically the same recipe of potassium chlorate and sugar as in the 19th century, [NurdRage] uses paper straws to contain this powder. Glue is used to section the paper straw into two compartments and seal in the components, with the smaller compartment used for a glass capsule containing sulfuric acid. This vial was produced from the tip of a glass pipette, using a hot flame to first seal the tip, then detach and seal the other end of the tip, resulting in the sulfuric acid capsule, ready to be added to the second compartment.

The moment this glass capsule is crushed, the sulfuric acid will soak into the paper, reaching the large compartment with the potassium chlorate and sugar mixture, causing a strongly exothermic reaction that ignites the paper. Yet as simple as this sounds, [NurdRage] found the three matches he made to be rather fickle, with one igniting beautifully after crushing the capsule with pliers, while one did nothing and the remaining match decided to violently explode rather than burn.

Considering the immense manual labor involved in making these matches, they never were very popular, and were quickly replaced by strike-anywhere matches, followed by safety matches, none of which require you to carry fragile glass capsules containing sulfuric acid with you. As a chemistry experiment, it is however a total blast that will set any boring chemistry class on fire.

Merry Christmas from PartsUnknown, Kentucky!

Ellern’s “Military and Civilian Pyrotechnics” has fascinating details on the history, chemistry, and current production of matches. Starts on page 64:

https://archive.org/details/Military_And_Civilian_Pyrotechnics_Herbet_Ellern/page/n71/mode/2up

Apparently some users of the promethean match would bite to break the glass vial. Biting a glass vial to release concentrated sulfuric acid…what could possibly go wrong? Seems that sense was about as common then as it is today…

As a retired chem prof I found the discussion of today’s safety match (strike-on-box) enjoyable. Fun fact: The sulfur in the match head is there partially to increase sensitivity to friction, and partly as a deodorant. The animal glue used as a binder burns with a less-than-pleasant odor. Burning sulfur covers that odor. And any pyrotechnician will point out that the fragrance of burning sulfur is both pleasant (in its own way) and addictive: “He who hath once smelt the smoke is ne’er again free” :)

I’ve never worked with potassium chlorate specifically, but I remember some of the cautionary notes regarding that compound and amateur chemists.

Potassium chlorate is highly reactive and will form an explosive mixture with many other chemicals. Some of the cautions in the list include: wear gloves, only make tiny amounts, be extremely clean and careful.

Apparently a tiny amount of contamination from a (for example) poorly cleaned mortar/pestle can cause the mixture to blow up in your face. It can react with the sulfur in your skin/body to form unstable compounds that will spontaneously ignite the rest of the sample, and so on.

Not saying “don’t do that”, but the warnings on potassium chlorate were so stark and forceful that you should take extra precaution here. Such as working with tiny amounts to debug your process and workflow before working with large amounts.

NurdRage is competent, but also note that this is a curated video and we might not see any of the failures he had along the way.

Also note that one of his matches blew up, so there’s that.

Thanks mom.

I’ve “worked” with it. Found a “chemical magic” book in the library as a teen that had a number of pyrotechnic recipes based on potassium chlorate, sulfur, and charcoal (with metal salts as colorants).

I learned THE HARD WAY that mixtures containing chlorate and sulfur tend to deteriorate over time, eventually spontaneously igniting.

Mixing a chlorate with concentrated sulfuric acid cuts out that “over time” part.

It’s no wonder that these matches were displaced from the market by those that used the much safer white phosphorus…

Not-very-fun fact: white phosphorus, taken internally, has about the same LD50 as sodium cyanide. If memory serves it’s slightly *more* toxic than NaCN.

That’s correct. On the match-head the white phosphorous was mixed with lead dioxide. The second half of XIX. century was full of cases with poisoning – especially amongst the workers of a match factory – crying for a much safer solution. Later white phosphorous has been replaced by the red phosphorous, a non-toxic allotrope, applied on the striking surface not on the head.

Look up phossy jaw, the safer matches weren’t safe for everyone.