Although the components of wood – cellulose and lignin – are exceedingly cheap and plentiful, combining these into a wood-like structure is not straightforward, despite many attempts to make these components somehow self-assemble. A recent attempt by [MD Shajedul Hoque Thakur] and colleagues as published in Science Advances now may have come closest to 3D printing literal wood using cellulose and lignin ink, using direct ink writing (DIW) as additive manufacturing method.

This water-based ink was created by mixing TOCN (tempo-oxidized cellulose nanofiber), a 10.6 wt % aqueous CNC (cellulose nanocrystals) and lignin in a 15:142:10 ratio, giving it roughly the viscosity of clay. The purpose of having both TOCNs and CNCs is to replicate the crystalline and amorphous cellulose elements of wood-based cellulose.

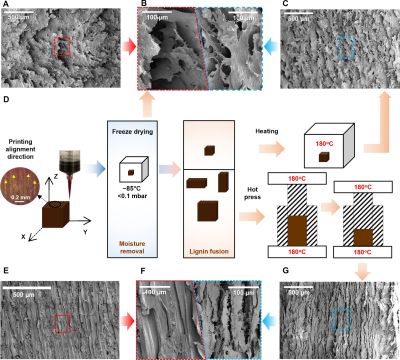

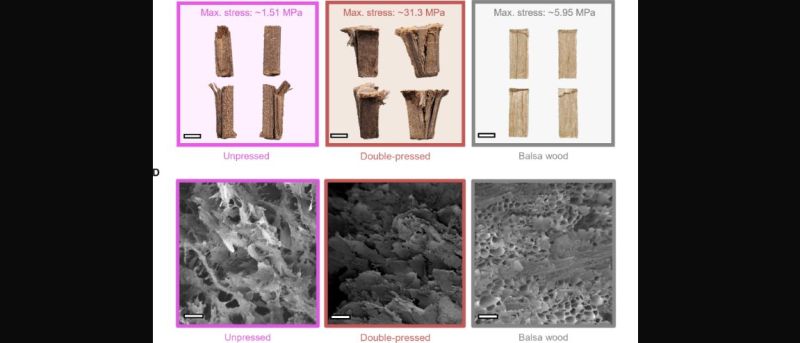

This ink was printed from a syringe head (SDS-60) installed in a Hyrel 3D Engine HR 3D printer. This printer is much like your average FDM printer, just targeting bioprinting and a wide range of heads to print and handle various attachments in a laboratory setting. The ink was extruded into specific shapes that were either freeze dried to get rid of the liquid component, or additionally also heated (at 180°C), with a third set of samples put into a hot press. These additional steps seem to promote the binding of the lignin and create a more durable result.

The produced samples were compared against the natural hardwood (balsa wood) which its ingredients were derived from. Not unlike with FDM printing, the heating and pressure seems to promote the annealing between the different layers, which themselves are somewhat similar to the growth patterns found in natural wood. Effectively, the more the samples were pressed in more directions, the better their properties, yet missing from the printed wood are the long fibers that naturally occur during the growth process.

Although promising, the researchers note that the involved steps of freeze drying and hot-press are energy intensive, not to mention cumbersome. These findings do raise the prospect of further developments of this basic ink formulation and post-processing methods which could making it more accessible and efficient. Perhaps one day DIW wood printing will become as much as a stable of hobby rooms and manufacturing facilities as FDM, SLS and SLA printing today.

… I am not sure I understand… Trees, do it all on their own (and much more efficently). Why on Earth would you want to *print* wood ?

Tried carving a small intricate statue?

Wood is also much easier to dispose of than plastic (multiple failed wood carving attempts!)

It just strikes me they have put in much too much research for such a use case– And, otherwise, if one lacks the requisite artesian skills N-axis CNC still seems way more resource efficient. Yet I have no idea what they have in mind.

excuse me scientists, i believe you have done too much science here. kindly tone it down

I had that reaction at first, but on second thought learning to turn biomass that would never have been turned into lumber (or was left over from cutting lumber) into a finished product still seems reasonable. We have paper and cardboard and various other products in the same vein.

I still don’t know if I would stop with a fake version of raw lumber, if for a similar effort I could instead try to mimic finished wood products. EG make it waterproof or at least rot resistant, flame resistant, insect resistant, dye/stain it, etc – many of the things we currently do with treatments and coatings applied after the fact. Just guessing, but maybe partial mineralization such as with silica, maybe just mixing in some lime and boron or an oil of some kind, such as one that polymerizes.

Redwood is already very rot-resistant by itself, and is sustainably farmed (for the most part). Teak is amazingly weather resistant and has a lot of silica already in it which makes it hard on cutting tools, but meh. It is also expensive but long term very cost effective and, I promise, way cheaper than this “energy intensive” 3d printed wood fiasco.

Cedar is bug resistant.

Purple woods exist. Lots of other colors too.

And you can definitely just put some lime or boron or oil *on* whatever wood you happen to have, this is called “finishing” and has been done since forever.

Wood is a mature technology. This project is silly. Grant money funding grab, yet another clickbait, whatever. Silly.

I thought it was pretty obvious that I was intentionally naming things that are already done to regular lumber. I even used the words “finished”, “coating”, “stain”, etc. Would it help if I had also called lime whitewash and said boiled linseed oil instead of a generic drying oil?

The point was, this field of research seems like it is taking ideas from cardboard and particle board, but trying to make a better product out of the same material. You’d only use the material that’s not a board and never was, because if you already have a good board you don’t need to destroy it to make a new artificial one. Oh, and kiln drying lumber can be energy intensive too, so there’s room for some energy consumption if they can get it down to a reasonable amount.

Because a piece of a tree is very useless as a speaker. It’s missing the holes, the design is all wrong.

There is an entire industry around modifying wood into something usable, as trees by themselves, are pretty useless if you don’t modify them into something else, such as lumber.

Or into furniture.

https://www.thisiscolossal.com/2016/12/full-grown-trees-grown-into-furniture-and-art-objects/

I see it the other way around. With a better understanding of industrializing cellulose and lignin, we may be able to do away with more plastics by using biodegradable materials in the same or similar processes. So, developing a usable cellulose+lignin FDM solution would be a very big deal; it’s not everything but it’s a start.

Imagine for a moment that lignin and cellulose can be grown in yeast or algae or e-coli (that double, or more every 24 hours ) and later printed into lumber or chairs or houses. This is why you would want to print wood

Maybe to form a specific woodgrain pattern for their project? Tree can’t be asked for form grain in a specific pattern but 3D printing lets you control the details to make for a more beautiful design

Some of us consider the natural grain of the wood that the tree or nature or whatever has come up with to be beautiful in and of itself.

Try carving sawdust without using phenol resins.

The linked article states in the first few paragraphs that demolition waste and other waste wood is a possible source. Lignin is a low value byproduct of paper production.

As an engineer at a forest products lab, lignin constitutes around 50% of the wood entering the paper mill and is typically burned to recover as heat, while also recovering the chemicals to feed back into the process. FInding value-added uses for lignin, especially as structural polymers, would be an excellent development.

While the knee-jerk question is, why not let trees do the assembly, many forests have large quantities of small diameter material that is costly to cut, transport and process. FInding economical processes to turn crooked, curved, bug-infested, or standing dead trees into products for which people will pay money would provide a “market pull” that pays for reducing the fire hazard, as well as locking up the CO2 in a persistent product. Big trees have low costs to harvest and transport. Little stuff, not so much. And unlike the eastern forests, rot can’t be counted on to turn scrap into CO2 for the next generation of trees.

coal is still a cheap AF method of generating power but is in no way the “best” other than an economics argument. Believe me, I worked as a fuels chemist I know how the whole “turn cheap useless byproducts into something useful” works.

.

Sadly, Recycling in general (except aluminum and other specific cases) is often more energy intensive and hazardous chemical producing than producing the virgin materials. Plastics I’m looking at you.

Attempting to repurpose useless sawdust, itself an extremely benign byproduct, will certainly fall into the same trap, there is massive historical precedent for this.

.

IMHO the proper move forward is to do the tough expensive R&D to remove the waste and byproducts on the front end while simultaneously moving toward nuclear power (the “greenest”) or investing heavily in actual renewable energy, probably not semiconductor based stuff (toxic materials etc) but large scale wind etc that mostly uses steel and copper- renewable but still long lasting materials. All of this is expensive by design- no more short changing the future for near term profits. Cost should be a tertiary concern at best. this will prompt serious consideration of the longer (more importan) term. But i’m just an internet moron so take that for what it is worth.

As a wood turner, I would like to get wood blanks that have the right moisture content in them. Wood is not just cellulose and lignin even though they are major components. There is sugar and other stuff in wood that makes it unique. The cell structure of growth rings, knots, etc can not be duplicated easily in 3D-printed wood. Having said that, there might be uses for structural beams, etc where a uniform wood structure like that from 3D printing may be preferred over natural wood.

If you can get cellulose and lignin (or Lignin-like compunds) from other sources like kelp, then you could grow kelp farms and stop cutting down trees. There is much more ocean area on the planet than land and Kelp grows much faster than trees.

against the natural hardwood (balsa wood)

is balsa considered hard?

If the tree is deciduous (i.e. loses it’s leaves each year) it is classed as a hardwood).

Doug Fir used in framing is a harder wood then balsa but it is classed as a softwood, because it is a evergreen.

Yes, balsa is ‘hardwood’.

It’s also very fast growing.

However you want the stuff that grew slowly in the shade. Much tighter grain. Hard to find.

Like old oak vs. newly cut.

So, can you print an Eames chair with it? Or a cedar strip canoe? Or any other bentwood product?

“I printed a wooden tobacco pipe with built-in cooling channels like the Merlin rocket engine.”

Or, eventually, straight grained, large format structural beams?