AVO meters — literally amp, volt, ohm meters — are not very common in North America but were staples in the UK. [TheHWcave] found an AVO 8 that is probably from the 1950s or 1960s and wanted to get it working. You can see the project in the video below.

These are very different from the standard analog meters many of us grew up with. [TheHWcave] shows how the dual range knobs work together to set the measurement. There are three separate ohm settings, and each one has its own zero pot. We were surprised that the meter didn’t have a parallax-correcting mirror.

Other than dirty switch contacts, the voltage measurements still worked. After cleaning the contacts, most of the ranges worked well, although there were still some issues. Some of the resistor ranges were not working, either. Inside the case were an old D cell and a square battery, a B121 15 V battery. Replacing the 15 V battery with a bench supply made things better.

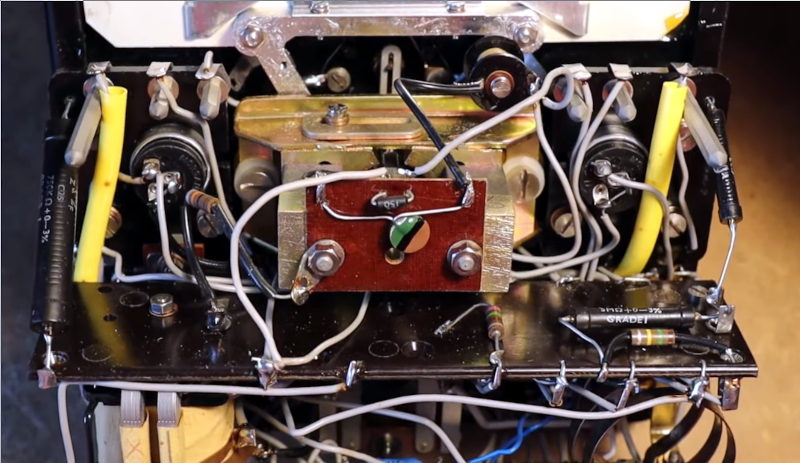

Some plugins are available to allow the meter to read low resistance or high currents. We thought using the soldering gun as a current source was clever. Once he gets it working, he opens the box around the 14:30 mark.

The inside was all hand-wiring and power resistors. Of course, there are also a ton of contacts for the switches. So it isn’t just an electrical design, but a mechanical one, too. The electrical design is also interesting, and an analysis of it winds the video down.

[Jenny List] has a soft spot for these meters, too. Why use an old meter? If you have to ask…

“We were surprised that the meter didn’t have a parallax-correcting mirror.”

I think it does, right at the bottom of the scale. In later models they moved it further up the scale because the curve of the scale does not match the curve of the case cutout. I don’t know why they did that, always jarred with me, I prefer the older models.

I love the overload cutout on these: no fancy over-voltage circuitry, just if you do something, anything, that sends the needle flying beyond the end of the scale, or backwards before 0, the needle itself trips a mechanical cutout and a button pops up. So 1950s simple!

Indeed. At the overview @00:40 you can see the mirror scales of the different models more clearly. And by this model it’s at the bottom side, and it’s also a bit dirty.

My father has one of these; it’s a lovely thing, and still works perfectly. Unfortunately it’s not so useful in the modern world because the voltmeter resistance is quite low, so connecting it across a component causes noticeable current flow and will disturb the circuit you’re working on. It’s be really interested to know if they can be modified to work around this.

Low input impedance is still quite useful for isolating current-sensitive faults in wiring like hairline cracks or corrosion. Even expensive meters often have a low-Z mode for isolating specific faults. I keep a few old VOMs with 2k, 10k, and 50k input impedance around for that purpose. Even with logic and low-power circuits, a low-Z move can help diagnose shorts, bad traces, weak outputs, bad capacitors, and other places where a few uA or mA make all the difference. Sure, it’s not suited to all measurements, but low-Z has always been useful.

Consider it a slightly more sophisticated version of one of those continuity lamp thingies which looks like a screwdriver with a battery and a bulb inside the handle

I can’t see any justification for the first sentence. Just because you call “wrenches” , “spanners” doesn’t mean we don’t use them.

Ampere-Volt-Ohm = Volt-Ohm-Milliammeter

That’s also technically more accurate. An Ampere meter movement would be rather useless for most electronics work.

I think you misunderstood. The sentence is in reference to the brand of the meter, AVO. Yes this type of meter is known as a VOM here in North America. The Simpson 260 is a fairly ubiquitous example in the USA.