[Chris Borge] was doing some fine tapping operations, and wanted a better way to position his workpieces. This was critical to avoid breaking taps or damaging parts. To this end, he whipped up a switchable magnetic vice to do the job.

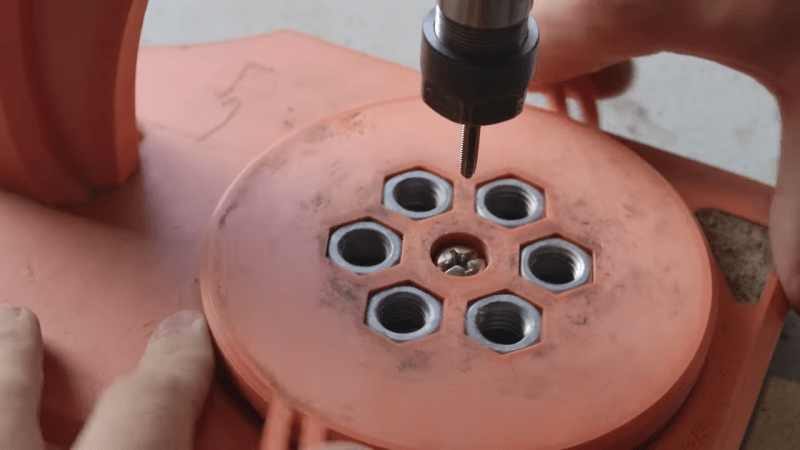

The key to the build is that the magnetic field can be switched on and off mechanically. This is achieved by having two sets of six magnets each. When the poles of both sets of magnets are aligned, the magnetic field is effectively “on.” When the poles are moved to oppose each other, they effectively cancel each other out, turning the field “off.” [Chris] achieved this functionality with 12 bar magnets, 12 M12 nuts, and a pair of 3D-printed rings. Rotating the rings between two alignments serves to switch the set up on or off. The actual switching mechanism is handled with a cam and slider setup which allowed [Chris] to build a convenient vice with a nice large working area. He also took special effort to ensure the device wouldn’t pick up large amounts of ferrous swarf that would eventually clog the mechanism.

It’s a neat build, and one you can easily recreate yourself. [Chris] has supplied the files online for your printing pleasure. We’ve featured some other types of magnetic vise before, too. Video after the break.

That’s a very clever approach to controlling magnets.

It has me imagining a robot with toggling magnets like this as a form of actuator. Less compact but more efficient than electromagnets.

Switchable magnetic base devices have been a thing for at least 25 years, possibly more. They are commonly used in machining to measure runout. If you plastic squirters took a Machining 101 class instead of trying to reinvent the wheel all the time, you would’ve known.

Indeed. Magnetic chucks for, for example surface grinders, as well as mag bases for dial indicators and many other uses have been around for ages. Since Grandpa at least because that is where I got my first one(s).

They “turn off” the magnet otherwise they would just collect chips and be unusable in short order.

Also LOL “you plastic squirters..” I’m gonna steal that, and I’m not even that old (is what I say)

Cad the Mad’s statement is still valid. That’s a very clever approach to controlling magnets.

25 years ago I was 7 years old. I am an electrical engineer, not a machinist.

Everyone has to learn something at some point. I am willing to bet you weren’t born with the knowledge and I wonder if you were ridiculed for not already knowing about this the first time you encountered it. Don’t ridicule others for learning something you already knew, especially when they’re from a different field.

“Plastic squirter”, yes because embedded system development is… plastic squirting?

https://xkcd.com/1053/

I have a big switchable magnetic chuck for my lathe, even in machining land it seems to be semi esoteric knowledge. Because every machinist I’ve ever shown it to has been amazed and never seen one before. They might know about dial indicator bases, but don’t think about it for work holding. And usually argue that they wouldn’t trust it because it would throw the workpiece when the power goes out, and I have to explain that it’s unpowered and works just like a big indicator base.

Just saying, the Plastic Squirter is way ahead of plenty of accomplished machining professionals. There’s nothing wrong with reinventing a wheel, to make a custom wheel that works for your purpose. Machinists do it all the time.

Yup, the first magnetic vice was invented in 1896. I was introduced to it in 1986 in metal work 101.

Looks like a fun project but can’t see using 3D printed anything for precision machine work.

Why not ? Your cast iron machine table was made of molten rocks poured into a mold made of sand before it was machined. Everything was crude at some point.

But once you machine the cast iron it is dimensionally stable, stiff, won’t get droopy with a little heat, massive enough it won’t easily be moved, vibration damping (to some extent), able to take a new tapped mounting hole probably where ever you might need etc – it is just a far better material for the task than plastic, and even most so than 3d printed plastic where the layer adhesion and infill are serious limitations.

Now as we are getting to the point of 3d printing in metals not being ‘impossible’ even for pretty large company and actually almost affordable as a contract service…

If you watch his other videos, you’ll see that he fills his prints with rebar and concrete to get the heft and stability. Most of the time the prints are just shells over a concreate slab.