If you came of age in the 1990s, you’ll remember the unmistakable auditory handshake of an analog modem negotiating its connection via the plain old telephone system. That cacophony of screeches and hisses was the result of careful engineering. They allowed digital data to travel down phone lines that were only ever built to carry audio—and pretty crummy audio, at that.

Speeds crept up over the years, eventually reaching 33.6 kbps—thought to be the practical limit for audio modems running over the telephone network. Yet, hindsight tells us that 56k modems eventually became the norm! It was all thanks to some lateral thinking which made the most of the what the 1990s phone network had to offer.

Breaking the Sound Barrier

When traditional dial-up modems communicate, they encode digital bits as screechy analog tones that would then be carried over phone lines originally designed for human voices. It’s an imperfect way of doing things, but it was the most practical way of networking computers in the olden days. There was already a telephone line in just about every house and business, so it made sense to use them as a conduit to get computers online.

For years, speeds ticked up as modem manufacturers ratified new, faster modulation schemes. Speeds eventually reached 33.6 kbps which was believed to be near the theoretical maximum speed possible over standard telephone lines. This largely came down to the Shannon limit of typical phone lines—basically, with the amount of noise on a given line, and viable error correcting methods, there was a maximum speed at which data could reliably be transferred.

In the late 1990s, though, everything changed. 56 kbps modems started flooding the market as rival manufacturers vied to have the fastest, most capable product on offer. The speed limits had been smashed. The answer lay not in breaking Shannon’s Law, but in exploiting a fundamental change that had quietly transformed the telephone network without the public ever noticing.

Multiplexing Madness

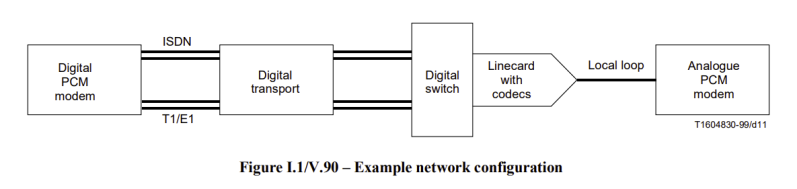

In the late 1990s, most home users still connected to the telephone network through analog phone lines that used simple copper wires running to their houses, serving as the critical “last mile” connection. However, by this time, the rest of the telephone network had undergone a massive digital transformation. Telephone companies had replaced most of their long-distance trunks and switching equipment with digital technology. Once a home user’s phone line hit a central office, it was usually immediately turned into a digital signal for easier handling and long-distance transmission. Using the Digital Signal 0 (DS0) encoding, phone calls became digital with an 8 kHz sample rate using 8-bit pulse code modulation, working out to a maximum data rate of 64 kbps per phone line.

Traditionally, your ISP would communicate over the phone network much like you. Their modems would turn digital signals into analog audio, and pipe them into a regular phone line. That analog audio would then get converted to a DS0 digital signal again as it moved around the back-end of the phone network, and then back to analog for the last mile to the customer. Finally, the customer’s modem would take the analog signal and turn it back into digital data for the attached computer.

This fell apart at higher speeds. Modem manufacturers couldn’t find a way to modulate digital data into audio at 56 kbps in a way that would survive the DS0 encoding. It had largely been designed to transmit human voices successfully, and relied on non-linear encoding schemes that weren’t friendly to digital signals.

The breakthrough came when modem manufacturers realized that ISPs could operate differently from end users. By virtue of their position, they could work with telephone companies to directly access the phone network in a digital manner. Thus, the ISP would simply pipe a digital data directly into the phone network, rather than modulating it into audio first. The signal remained digital all the way until it reached the local exchange, where it would be converted into audio and sent down the phone line into the customer’s home. This eliminated a whole set of digital-to-analog and analog-to-digital conversions which were capping speeds, and let ISPs shoot data straight at customers at up to 56 kbps.

This technique only worked in one direction, however. End users still had to use regular modems, which would have their analog audio output converted through DS0 at some point on its way back to the ISP. This kept upload speeds limited to 33.6 kbps.

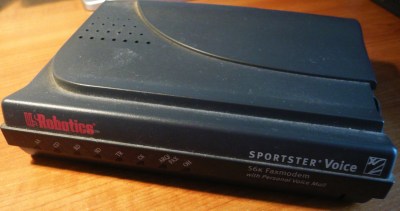

The race to exploit this insight led to a minor format war. US Robotics developed its x2 standard, so named for being double the speed of 28k modems. Rival manufacturer Rockwell soon dropped the K56Flex standard, which levied the same trick to up speeds. ISPs quickly began upgrading to work with the faster modems, but consumers were confused with the competing standards.

The standoff ended in 1998 when the International Telecommnication Union (ITU) stepped in to create the V.90 standard. It was incompatible with both x2 and K56Flex, but soon became the industry norm.. This standardization finally allowed for interoperable 56K communications across vendors and ISPs. It was soon supplanted by the updated V.92 standard in 2000, which increased upload speeds to 48 kbps with some special upstream encoding tricks, while also adding new call-waiting and quick-connect features.

Final Hurrah

Despite the theoretical 56 kbps limit, actual connection speeds rarely reached such heights. Line quality and a user’s distance from the central office could degrade performance, and power limits mandated by government regulations made 53 kbps a more realistic peak speed in practice. The connection negotiation process users experienced – that distinctive modem “handshake” – often involved the modems testing line conditions and stepping down to the highest reliable speed. Despite the limitations, 56k modems soon became the norm as customers hoped to achieve a healthy speed boost over the older 33.6k and 28k modems of years past.

The 56K modem represents an elegant solution for a brief period in telecommunications history, when analog modems still ruled and broadband was still obscure and expensive. It was a technology born when modem manufacturers realized the phone network they were now working with was not the one they started with so many decades before. The average consumer may never have appreciated the nifty tricks that made the 56k modem work, but it was a smart piece of engineering that made the Internet ever so slightly more usable in those final years before DSL and cable began to dominate all.

Thank you! I have wondered how a 56k modem work with a 64k digital system without any way to synchronize the samples.

What about 115 kbps HIS by Ericsson?

HIS was purely digital … Similar to ISDN. Very popular in Poland in 90’s , known as SDI – Szybki Dostęp do Internetu

That’s also why nowadays if you talk on a landline you may not be able to talk at the same time, you won’t hear the person on the other end while you talk as a result of the digital compression, makes it cheaper for the phone company

Cell phone to cell phone may not have that issue

Back in the realtek ac’97 days, needed a catch a call dongle attached in series with the computer and phone Line

Because either of someone called while you’re on the Internet either you got disconnected, or the phone won’t ring, they hear this ear rape screeching of the modem, or possibly a busy signal

Are you sure that’s true? I don’t use a cell phone, only a landline, and the irritation you speak of only happened when I was talking to someone who was on a cell phone. (The cell phone also had the irritating delay.)

Many, MANY “land lines” these days are actually provisioned as VOIP service running over the packet data network (including any land-line service delivered by a cable company or other non-telco network provider), so yeah in those cases you have all of the same digital-communication hazards as cell phone users.

Per my limited understanding, VOIP shouldn’t be subject to the delays I think are caused by the cell system’s TDMA (time division, multiple access) though, where the cell site rotates, although very quickly, which customer it is serving, which cannot be done without delays.

i used the heck out of my 14.4kbps modem, and by enlarge it always connected at 14.4. there was some variety whether it would use v32 or v42bis, which i think had more to do with the modem on the other end. and i certainly got to know the handshake sounds and what kind of speeds they foretold. but mostly, it was consistent. and man! it was a big step up over the 2400bps that came with our 286!

i used a 56k modem only briefly, and that thing was different every time. sometimes it would be fast, sometimes it would be slow. sometimes it wouldn’t connect at all. so in my mind, 14.4k is still the max…anything above that is flying too close to the sun for our actual existing POTS system, apparently. by the time 56k modems proliferated, hardly anyone was using them. a last gasp of a technological dead end

Distance and line quality is all, I was 3.1 miles from the exchange according to the TDR the tech used, I got reliable connects at full speed on most of the ‘real’ V34 modems I had (some of the crappy Winmodems were really poor) and when I got 56K modems, I almost always got connects over 50K.

They were fairly quickly outpaced by ADSL but in the UK at least, 56K modems were around for a good few years and most ISPs offered 56K service for quite a while after ADSL became available because it wasn’t cheap.

I was in Serbia at that time (in the early 2000s) and usually had a reliable connection at 53.3 kbps, though sometimes, due to weather or bad luck, it dropped to 33.6 kbps. I’m not sure, but I think I even saw 56 kbps few times. However, that was a long time ago, so maybe I just imagined it.

I think you mean by and large

Obviously, and that particular flub reeks of a voice-to-text transcription error.

Computers will EVENTUALLY get just as good or better at listening to us talk and figuring out what we /really/ said as picky, pedantic humans like (presumably) the both of us already are… but probably not in my lifetime.

One thing that lots, and lots, and lots of people did not know or realize, is that you needed to ground your computer system properly, if you were using an internal modem. I had lots of problems like you too, when I had a 56K modem. For a while I just thought it was bad luck, too far from the exchange or something. Until one day I had ran out of sockets and took an extension cord and plugged my computer into one of the kitchen wall sockets. And lo and behold, I got 55K the first time. No disconnects, no retrains, nothing, just worked.

So I investigated. It turned out the the socket under my desk and the socket in the kitchen were in the same group (they were both in the kitchen divider wall). In the kitchen, ground was properly connected in the socket (mandatory for a “wet space” as we call it). But in the socket under my desk, on the other side of the divider wall had no ground wire.

As both sockets were connected to the same group, I just ran a ground wire from the kitchen socket to the socket under my desk (about 1 meter, I don’t understand why it wasn’t done in the first place).

And after that, I had such a good connection that I actually learned how to properly kick butt in Quake 2. :P

Many people suffered from this grounding issue. I ‘fixed’ this problem for many of my friends, just by telling them to run an extension cord from their kitchen. ;)

It was only a problem when you were using an internal modem. I think the noise/ground issue happened because most PC power supplies had the bare minimum of line noise filtering (single line single phase I think it’s called). Without a ground connection, the line filter could not properly do its work. Or maybe it was causing ground buzz, I don;t know. I didn’t have the knowledge or even an oscilloscope to properly figure it out at the time.

If you used an external modem, you had no issues. They were self-powered. Only, you should make sure to plug the modem into the same socket/group as the computer, otherwise you could have issues again.

Soon after, I switched to ISDN though. Fully digital, and it didn’t suffer the same ground problem as the 56K modems. And my ISP (XS4All) supported channel bundling for free too. So I had 128KBps to kick ass with!

Man i remember XS4ALL from playing counterstrike 1.6 – they hosted a lot of public servers

Interesting. I insisted that my modem be external, because I had heard of too many problems with the internal ones; but now I don’t remember what those problems were, or even whether or not I had any idea at the time. I never had any trouble with my external modems. From my old email records, it looks like I didn’t have DSL until 2007. During the 2nd Gulf War, I was able to watch video on what I think was a 14.4kbps modem. I definitely did not have 56K yet, and I don’t think it was even 28.8. It was a very small frame, and only 16 colors, but it was kind of exciting that I could get actual video of the war almost as it was happening.

I don’t remember how long I might have had 56K before I had DSL. Some people think of DSL as being super slow; but two or three of us could be watching video at the same time, in 360p, with no slowing. When Verizon started their FiOS campaign off with “This is big!” and was pushing it so hard, they came to the door countless times trying to get us to switch, and they said things like “The copper is costing us too much to maintain,” and my response was, “Then why are you trying to move me to something more expensive?!” They’d also say, “With fiber-optic, you can download a feature-length movie in six seconds,” to which I would reply, “What in the world use do I have for that?!” We had DSL until my wife had to teach on Zoom during the COVID political pandemic and apparently every little frame, one for each student, required as much bandwidth as it would if they were the only one, and then the DSL couldn’t keep up, so we had to go with the fiber-optic, and spend more per month.

Most likely, the main problems you were trying to avoid with internal modems were: (a) overheating issues; and (b) RFI noise on the line. (Think about what speakers connected to an analog soundcard typically sound like, if it’s either built into the motherboard or attached in the form of an unshielded PCI/PCIe card… and now remember that every data modem IS an analog audio interface!)

External modems just tended to be more robust. The serial cable was, in no small part, acting as an isolator from the pervasive EM fields buzzing all through the rest of the system. Ditto having an external power source. My USR modems were beasts, in all the best ways.

Er, every *dialup data modem. Your cable- or fiber-modem does plenty of modulating and demodulating, but it is not in fact squealing audio waveforms down electrical wires the way telco modems do. And therefore enjoys a level of immunity to RFI that dialup modems, internal OR external, could only dream about.

As dial-up became popular PC manufacturers began offering “soft” modems that relied on software and the system CPU for signals processing, while hardware/external modems usually provided dedicated hardware for those workloads. This meant the quality of your connection could vary based on your system’s load in addition to the quality of the line. Worked at a ISP in the 90s where we offered 56k dial-up and I remember a plague of customers unhappy that they would never connect at the advertised speeds.

It was long enough ago that I don’t remember details; but I think it was software-related. Also, my PC back then had ISA, not PCI, and I was always bringing up the rear as far as speeds go, always being a couple of generations behind most people.

now you tell me!

i always assumed the transformer on the modem was supposed to take care of that but i didn’t give it much thought.

When I had my hot-rod 286 with 4MB RAM, sound card, CD drive and Windows 3.1,

the 2400 Baud modems were already in the museum. Like acoustic couplers and C64s were.

The slowest modems that could be bought used were 14k4 data/fax modems.

I had such a modem, I think. Or was it an 28k8 model?

Anyway, it was okay for visiting mailboxes or T-Online or CompuServe.

Other users had special BTX modems running at 1200/75 Baud or 1200/1200 Baud depending on model.

But these were single-purpose modems, not usable for anything else other than T-Online Classic (BTX).

Users with brains (not me) had opted for an Fritz! ISDN card for ISA bus.

Browsing data banks and mailboxes that way must have been a breeze.

ISDN was incredible reliable. Slow as as a digital connection in retrospect, maybe, but way more reliable than DSL!

i came the same conclusion too by listening to handshakes all over the country obsessively…

i feel like i saw 19.2kbit disproportionally with my hardware :-) in CA bay area. Back in the war driving days.

funnily enough I went through this very situation in the late 1990s/early 2000s.

our home computer shipped with one of those awful 56K softmodems which could never get a stable connection.

we ended up going back to our 33.6k modem which was rock solid by comparison. took us all the way through until we got cable.

All these decades later I still have the dialup sound burned into my head with with perfect clarity.

It’s my ringtone haha

This was the time when ISDN with 64 KBit/s sold very well in my country.

Some users used channel combining and had 128 KBit/s,

at the expense off loosing the second telephone line while surfing.

Is it really an “expense”, when nobody can interrupt you with a phone call while you’re playing CounterStrike? :P

Well… in the days before pervasive cellphone hip-grafting, when the only way anyone could reach you while your line was tied up was to either drive over to your home, or hope that you gave them your pager number?

…Holy shit, 30 years ago was a crazy place to live. Sometimes I forget just how preposterous our lives really were.

Back in the day, one played a lot of Day of Defeat and Action Quake, the nifty isdn cost me over 1k € per month thanks to the per minute charge. Naturally, having only one provider meant they were really dragging their feet with introducing ADSL. Ditched them the second there was a stable 4G network.

The 53k limit only applies to USR’s x2 protocol. K56Flex and V.90 didn’t run awry of power (dB) limits and therefore could eke out slightly higher speeds.

Check out magviz.ca. I had a ddial running back in the 1980’s. 7 modems, 7 phone lines.

300 baud of pure text chat. I did have Zoom 28.8k modem, but the chat system was a marvel for its time.

Met my first love on that thing. The modems were SSM Modemcards for the //e.

working with a Credit Card Processing Company they had a way to connect at a lower baud rate (say 1200), perform less hand shaking and deliver their data payload in less then the 6 second time slot that was a billable unit. This meant they cut their phone bills in half compared to connecting at a higher baud rate. The higher baud rate connection took longer to get connected and then deliver data. This company had a 50% advantage in their costing structure.

I’ve seen this firsthand. Back in 1997 when I was first accepting credit cards, my processor did support high speed modems but the 28.8k handshake took 10-15 seconds, just to process a few hundred bytes of CC data. Dusted off my old 2400 bps modem, it would call, handshake, send the batch and be done in the same amount of time.

Oh, no question if you didn’t NEED every last kbps of bandwidth, performing the entirety of a v.90 handshake sequence was a massive time-sink. Bodegas and supermarkets in NYC still often have dial-out card processing terminals, and yeah… starting from dial tone, they can perform an Entire card transaction quicker than it takes a 56k dialup handshake to finish the v.8 frequency sweeps.

(That:s the pair of distinctive “boing” sounds in the middle of the handshake, when the modems quickly ramp through basically their entire available frequency range to determine which ones can be “heard” on the other end. The resulting frequency “constellation” ultimately decides where in the 33.6kbps 56kbps range your actual connection speed will land.)

Brief, yes, but the window between v.90 and DSL and DOCSIS that ISDN inhabited was shorter still.

There was also shotgun connections that people did from baud all the way till the last v92 56k service; they broke 100kbps using cross-modulation with two-lines. AT&T still has a POTS service in 2025; it’s copper all the way to the local switch. You still see splicing pedestals and trunk boxes in rural parts of the US..

Fond memories of working for a regional ISP. We only supported K56Flex. Most people couldn’t get much beyond about 44k, but once you’d done it for a while you could recognise what speed it would connect at by listening to the rise and fall of the negotiation hissing.

We all developed a bunch of strings to do things like change flow control, maximum speed and error checking and to this day I remember the one that worked on about 80% of modems, assuming you wanted to throttle them to 44K

AT&F&C1&D2&K3%C0+MS=,,,44000

I used to know what each part did but that has been lost to age, coffee and alcohol.

The previous residence had POTS. No mobile phones, so we asked the LEC for a 2nd line, said it was for a fax machine, so we could use voice and data simultaneously. Rather than run an additional copper pair to the house, they installed a PairGain unit. It worked, but we never got faster than 28.8 Kb/s.

When we moved here 25 years ago, we were part of the LEC’s 250-home trial rollout of that new-fangled ADSL service. Some years later, when the remnants of Hurricane Ike came through, the mains power went off (and stayed off for days, as it turned out). We couldn’t power the DSL modem, but the dialtone was still there. My wife’s laptop had a modem, so we used that to connect via dialup and scope out the situation. Our 14-year-old heard the modem negotiation, and asked “what’s that?” — she had never heard the song of the modem before.

The LEC discontinued service over copper a couple of weeks ago, so no more DSL and POTS; it’s fiber to the house now. Faster connection, but one more thing I have to worry about battery backup for.

I remember downloading 94MB file using NetZero (they ran a banner ad, and played a tiny commercial video while you were dialing in). I remember them limiting soon after, claiming a few users were taking 94% of their bandwidth.

I had heard that it was digital downstream, cool to hear a bit more of that side of the story.

Coming soon: NetZero TV

One of the selling points of many of the 56k modems was that they had “Upgradable ROMs”.

Did anyone EVER upgrade a modem? I don’t believe I ever saw any kind of upgrade actualy offered for these “furure proofed” modems.

Yes – had a Courier that started as 33.6, then went to x2 then later to V90. That modem also saw multiple lighting strikes and survived, only to be murdered by water when it went into the cleaners bucket.

So… it basically it used the digital part of the phone network directly as a form of network and moved the modem from the ISP to wherever the phone company’s transition from digital to analog occurred. Right?

Does that mean that with a good connection via an old-school analog phone switching system, if home computers and ‘fast’ modems had co-existed with those in time then people could have had 56k via plain old analog modems?

Basically old-fashioned phone lines used frequency multiplexing so only 4000Hz bandwith slots existed, with some filtering I think 3200Hz was available – this differred per county and even technology, which works out to about 36kbps.

When everything up to the last mile became digital, there was no need to limit a bandwith slot. Theoretically near-infinite bandwith was now available – shown by those same twisted pair now supporting ADSL with hundreds of megabits per second. But in the analog world bandpass filtering (not necessary intended as such) still existed – as well as the 64kbps bandwith of the digital signal, so that was what limited the actual data to about 56kbps.

I still have my US Robotics 28.8 and another 56k that I used for a few years. I listened to many hours of a podcast along with downloading stuff since that’s all I had. Now the last couple years I finally got TMobile wireless in my semi-rural area.

The actual technology leap was FSK or Frequebcy Shift Keying. FSK is what pushed copper pairs up to 56K, and no matter how “digital” the technology became in the background that last mile was still a twisted copper pair.

No mention of robbed bit signalling? That’s why it’s 56kbps instead of the theoretical 64kbps that 8×8000 works out to.

If I recall, the telecom would pare off the least significant bit for a low bit-rate, in-band signalling channel. Analog voice would never notice, but it allowed for inter-switch communication via trunk calls that did not rely on out-of-band control like SS7.

The Hayes AT command set is alive and well in GSM mobiles and IoT devices

A DS0 chrome extension for VoIP?