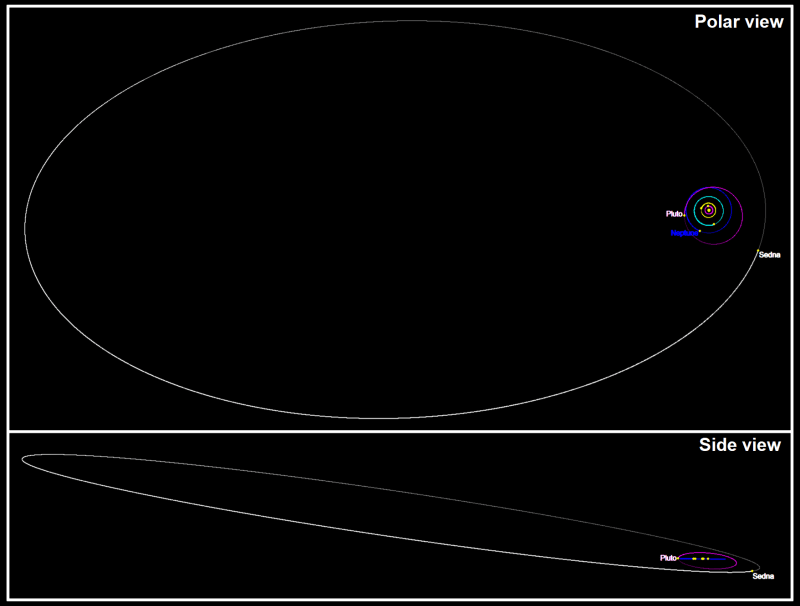

While for most people Pluto is the most distant planet in the Solar System, things get a lot more fuzzy once you pass Neptune and enter the realm of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). Pluto is probably the most well-known of these, but there are at least a dozen more of such dwarf planets among the TNOs, including 90377 Sedna.

This obviously invites the notion of sending an exploration mission to Sedna, much as was done with Pluto and a range of other TNOs through the New Horizons spacecraft. How practical this would be is investigated in a recent study by [Elena Ancona] and colleagues.

The focus is here on advanced propulsion methods, including nuclear propulsion and solar sails. Although it’s definitely possible to use a similar mission profile as with the New Horizons mission, this would make it another long-duration mission. Rather than a decades-long mission, using a minimally-equipped solar sail spacecraft could knock this down to about seven years, whereas the proposed Direct Fusion Drive (DFD) could do this in ten, but with a much larger payload and the ability do an orbital insertion which would obviously get much more science done.

As for the motivation for a mission to Sedna, its highly eccentric orbit that takes it past the heliopause means that it spends relatively little time being exposed to the Sun’s rays, which should have left much of the surface material intact that was present during the early formation of the Solar System. With our explorations of the Solar System taking us ever further beyond the means of traditional means of space travel, a mission to Sedna might not only expand our horizons, but also provide a tantalizing way to bring much more of the Solar System including the Kuiper belt within easy reach.

Funny thing is that Neptune was the most distant planet from the Sun until 1999: Pluto was closer. Then Pluto became the farthest planet until 2006, and after that Neptune became the farthest planet again.

Sorry Jerry but: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aIVOIaYxaTo

The line between science and science fiction tends to get quite blurry with proposed propulsion methods.

Good science fiction is a form of science, I’d say. :)

The main difference is that it is being excercised in the minds of people.

In a psychical environment, rather than a physical environment.

Right then. I’ll just get to work on the Infinite Improbability Drive.

Watch for incoming whales!

Not again!

+1

The “classic” Sci-Fi authors were usually terrible writers and storytellers. They weren’t interested in writing good prose, they wanted to speculate and develop “neat ideas” and the fiction was simply a platform or an excuse for that. They were so captured by that one idea that they didn’t even care what the rest of it looks like, and some even argued that the writing should be bad in order to not get in the way. Good Sci-Fi in this sense is very similar if not overlapping with the typical writings of some people “on the spectrum” who are writing compulsively about their narrow special subjects of interest, whatever that might be.

So there’s a fine line between scientific speculation and simply obsessing about a concept and forcing the conclusions into writing, and neither of them are particularly interesting or enjoyable to read unless you happen to share the same passion.

Meanwhile, good Sci-Fi in the technical artistic sense that is actually readable and watchable, containing compelling storylines, characters, comedy and drama, is typically lacking in the speculative science part entirely and hand-waves it away as storytelling magic because it would detract from the rest of it. It’s not science fiction anymore, it’s science fantasy.

Any sort of controlled rocket was science fiction when proposed.

A rocket reaching the Moon was science fiction when proposed.

A rocket reaching Pluto was science fiction when proposed.

A rocket using ions instead of fire was science fiction when proposed.

Two things are universal in science: Every proposal is science fiction until someone makes it work, and people who can’t do anything useful with their lives discount proposals as science fiction.

I agree with you 100%. Think about something we see as a simple device or technology in the house like a TV. This was thought to be nothing more than a far fetched theory at one time. Most didn’t even attempt to make it come to life because they were too close minded. If you can think it then one day there is a chance for it to become reality. I have great admiration for those who test the limits in something that is conceived as science fiction because these are the individuals that change the world.

I think this is projecting modern ideas backwards and thinking that someone was fantasizing about an actual television without any idea how one would work. That’s a witch’s magic mirror you’re describing there, straight from myth and tales, and of course it could be dismissed with just as much reason as was needed to create the idea.

For the actual invention, you have to look at the ideas leading up to it: the first long distance facsimile machines used swinging pendulums to scan a page. That gave people an idea, but you couldn’t hope to make a pendulum swing fast enough to draw a live moving picture so they tried spinning discs and mirrors and drums – and it didn’t work. They could not make it work. The naysayers were right until vacuum tubes came out of the left field and solved the problem – but nobody could predict that and argue that it had to come.

That’s the major flaw of speculation and extrapolation. No amount of “open-mindedness” is going to make magic happen, and if “magic” actually does happen in some form and things turn out your way, you still can’t take credit for something you actually didn’t predict because your hypothesis was wrong or entirely missing. In other words, you were predicting the witch’s magic mirror and you got an LCD flat-screen instead.

That’s reading the history backwards.

People discovered rockets first before they had the idea they could fly to the moon with them.

In fact, outside of completely fantastical ideas like getting carried to the moon by a gondola pulled by trained birds, the most plausible early Sci-Fi idea for moon travel was probably Jules Verne’s moon shot cannon (1865). His story was made into a movie in 1902. Today we know that while you could in theory build such a cannon and hit the moon, the acceleration would not be survivable.

It was the astronomer William Leitch who first proposed the possibility of using rockets to travel in the vacuum of space (1861) followed by the rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky who calculated how much fuel would be required to reach space and showed that liquid fuel rockets could have the required energy density in 1903.

While the science fiction was barking up the wrong tree, Robert Goddard and others showed that liquid fuel rockets were actually possible (1914 – 1926) and then the idea of traveling to the moon by rockets was seriously picked up by science fiction writers, with books like The Rocket to the Moon (Thea von Harbou, 1928) or The Conquest of Space (David Lasser, 1931). At that point it was already a scientific fact that you could – it was just not tried yet.

The science fiction writers are always one step behind the actual science, because guess where they get their inspiration from?

Not really. It was proposed in the late 19th century when people discovered that high voltage electricity can move significant amounts of air. Electrostatic attraction was a well known phenomena by then. They first tried to make airplanes fly using the effect, but then quickly realized that it is too feeble and would only really be useful in the vacuum of space.

Ion thrusters were known to work for at least 50 years before the space race. It was science fact to begin with, and then the popular fiction picked the ball and ran with it, inventing all sorts of fantasy versions that had nothing to do with science.

Yeah. They 1000% need to invest in and develop that direct fusion drive.

My only disappointment is that these craft blow past their targets giving a rather limited window of observation time. Such extreme speeds would mean even shorter windows.

From a budgetary perspective it shortens the mission operations from over a decade to a manner of years. These qualities give any proposed mission a much better chance at approval.

An orbital craft seems to offer more data. We could have a weather service for Pluto much like Jupiter and Saturn missions. Tradeoffs are tough, I waited a very long time for data from New Horizons, and as revolutionary as it was the window for photography was very short.

Not the fusion concept. It actually has the ability to do an orbital insertion, which is absolutely NUTS if you know anything about how difficult that is.

I must have just assumed its velocity wouldnt allow such a thing. That is bonkers really, I am assuming you reverse the engine orientation and apply equal thrust to brake?

That’s how you brake in space.

A space probe with an ion thruster and a solar array has about 1-10 kW of power when it’s close to the sun. The fusion drive has a power budget of 1-10 MW or a thousand times more regardless of the distance to the sun, which gives it the ability to make some moves.

Wait, Neptune was further away than Pluto I’m 1999? Hmmm… I don’t remember that… I have to check that out. Unless of course if you mean because the demotion of Pluto as a planet then the promotion back to planet again, the okay yeah that makes sense. That’s probably what you mean, got it!

No it is meant literally. Plutos elliptical orbit brings it closer to Earth than Neptune for about a fifth of its orbit.

Oops I mean “IN 1999” darn autocorrect.

I am not an astronomer, so whatever. But to my simple little mind, if the orbit is so eccentric that the major axis is outside the heliopause, then how can we assume that the object was from the original accretion disk that formed the solar system, and was not captured?

A larger object outside Sedna which orbits the Sun could also explain orbital perbutations. A satellite mission could help answer these questions.

By spectroscopic evidence that it’s made of the same materials as other trans-neptunian objects.