One reason Forth remains popular is that it is very simple to create, but also very powerful. But there’s an even older language that can make the same claim: LISP. Sure, some people think that’s an acronym for “lots of irritating spurious parenthesis,” but if you can get past the strange syntax, the language is elegant and deceptively simple, at least at its core. Now, [Daniel Holden] challenges you to build your own Lisp as a way to learn C programming.

It shouldn’t be surprising that LISP is fairly simple. It was the second-oldest language, showing up in the late 1950s with implementations in the early 1960s. The old hardware couldn’t do much by today’s standards, so it is reasonable that LISP has to be somewhat economical.

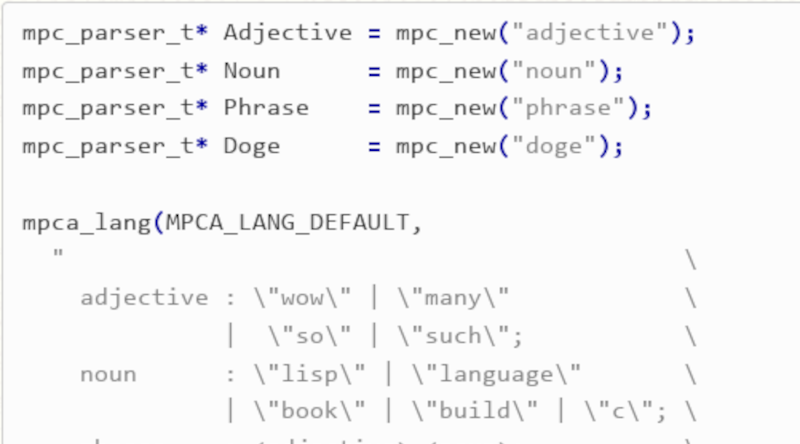

With LISP, everything is a list, which means you can freely treat code as data and manipulate it. Lists can contain items like symbols, numbers, and other lists. This is somewhat annoying to C, which likes things to have particular types, so that’s one challenge to writing the code.

While we know a little LISP, we aren’t completely sold that building your own is a good way to learn C. But if you like LISP, it might be good motivation. We might be more inclined to suggest Jones on Forth as a good language project, but, then again, it is good to have choices. Of course, you could choose not to choose and try Forsp.

Neat! I am always grateful when authors make their book freely available. This may be the thing that finally lets me understand C.

This book will also join the Make-a-lisp project (https://github.com/kanaka/mal) on my TODO list. Make-a-lisp also takes you through building a lisp interpreter but lets you pick the language. There are examples from 95 languages (so far!).

“LISP has been jokingly described as “the most intelligent way to misuse a computer”. I think that description a great compliment because it transmits the full flavor of liberation: it has assisted a number of our most gifted fellow humans in thinking previously impossible thoughts.”—

Edsger W. Dijkstra, 1972 Turing Award Lecture, CACM (Communications of the ACM) 15 (10), October 1972.

As I recall, in the 1980s, LISP became a language for programming artificial intelligence, partly it allowed self-modifying programs.

Might be PROLOG.

My favorite LISP-like has always been TCL, though everyone keeps thinking it’s C when they see the syntax.

SCHEME comes to mind.

Sheme is just a dialect of Lisp. Try writing C code into a TCL interpreter and you will be sorely disappointed.

LISP came up when I looked into Nyquist in Audacity. It’s nice to have a code prompt to work on audio. I read a LISP tutorial every coding session, I seem to forget the syntax every time

cheat sheet:

()

“code is [or can be] data and data is [or can bbe] code” is an important thing to remember in any system. Not because it’s true in any given language or hardware (it’s not), but because in most hardware it’s possible for a program to be able to treat any given block of memory as writeable data (“read+write”), muck with it, then treat it as code (“read+execute”). If that program is hostile and the memory block is something that the rest of the system assumes is only data or only code, bad things can happen.

To demonstrate the concept (without delving into maleware): When talking to novices, I ask them “is that [insert interpreted language here] program you wrote code or data?” If they are running it through the interpreter, it might as well be considered code. If they have it loaded up in their text editor, it’s data. For compiled code, if you load it up in your hex editor, it’s data, if you ask your processor to run it, for all practical purposes, it’s code.

heh that’s not what i think when i think that code and data are interchangeable. my mind goes straight to the stunning and delightful fact that compilers exist and are in fact quite straightforward

Is that byte NOP or is it just a data value of 0x90?

Best way to learn – do a project, solve a real problem etc. Good to have such tutorials.

I’ve come up with a more useful acronym to remind me of one of the reasons why LISP (all caps for the old style when referring to the language and when defining an acronym, or in this case a backronym) is so expressive: LISP = Links Inside Surrounding Parentheses.

Links are just another way of saying Pointers.

Not everything inside LISP parentheses are “lists” (ex: cons cells like (A . B), binary trees, associative lists, etc.), so Links (aka Pointers) cover both “cons cells” (ex: (cons ‘A ‘B)) and the other data structures supported by LISP that are built on top of cons cells like lists.

I don’t know if AutoCAD still allows users to employ LISP to program custom actions in the drawing environment, but AutoCAD 13/14 (mid 90s iirc) would let you make your own menus and procedures, etc. I was self-taught in BASIC (C64, ZX81, Atari and generic) and LISP was similarly easy for what I needed it for. I never got really into the guts of it but now I would like to explore it more

AutoLISP is one of the many scripting languages supported by AutoCAD, and in some ways the best supported because it’s been around the longest. I’ve even had a bit of luck vibe coding simple scripts with ChatGPT

Old:

‘If you’ve had luck doing stupid things, you are stupid and lucky so far.’

Also, wouldn’t C with a LISP be pronounced, “Thee?”

why does hackaday use the royal we. it weirds me out acting like all authors have the same opinion, we are the hackaday, resistance is futile, you will be assimilated.