Despite the best efforts of modern medicine, Huntington’s disease is a condition that still comes with a tragic prognosis. Primarily an inherited disease, its main symptoms concern degeneration of the brain, leading to issues with motor control, mood disturbance, with continued degradation eventually proving fatal.

Researchers have recently made progress in finding a potential treatment for the disease. A new study has indicated that an innovative genetic therapy could hold promise for slowing the progression of the disease, greatly improving patient outcomes.

Treatment

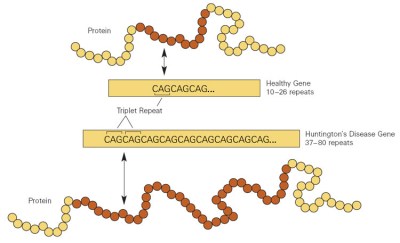

Huntington’s disease stems from a mutation in the huntingtin gene, which is responsible for coding for the huntingtin protein. This gene contains a repeated sequence referred to as a trinucleotide repeat, where the same three DNA bases repeat multiple times. The repeat count varies between individuals, and can change from generation to generation due to genetic mutation. If the number of repeats becomes too long, the gene no longer codes for huntingtin protein, and produces mutant huntingtin protein instead. The mutated protein eventually leads to neural degeneration. This genetic basis is key to the heritability of Huntington’s disease. If one parent carries a faulty gene, their children have a fifty percent chance of inheriting it and eventually developing the disease themselves. Over generations, the number of repeats can increase and lead to symptoms appearing at an earlier age.

The new treatment relies on advanced genetic techniques to slow the disease in its tracks. It involves the use of a custom designed virus, which is inserted into the brain itself in specific key areas. It’s a delicate surgical process that takes anywhere from 12 to 18 hours, using real-time scanning to ensure the viral payload is placed exactly where it needs to go. The virus carries a DNA sequence and delivers it to brain cells, which begin processing the DNA to produce small fragments of genetic material called microRNA. These fragments intercept the messenger RNA that is produced from the body’s own DNA instructions, which is responsible for producing the mutant huntingtin protein which causes the degenerative disease. In this way, mutant huntingtin levels are reduced, drastically slowing the progression of the disease.

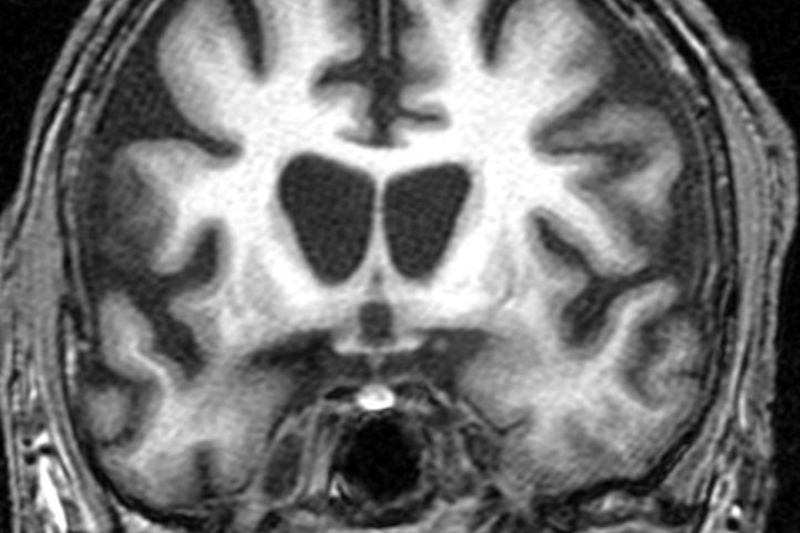

The effects of the treatment are potentially game changing, with progression of the disease slowed by 75% in study patients. Results indicate that with effective treatment, the decline expected over one year would instead take a full four years. In more qualitative areas, some patients in the trial have managed to maintain the ability to walk at a point when they would typically be expected to require wheel chairs. In typical Huntington’s cases, the onset occurs between 30 to 50 years old, with a life expectancy of just 15 to 20 years after diagnosis. The hope is that by delaying the progression of the disease, affected patients could have a greater quality of life for much longer, without suffering the worst impacts of the condition.

The initial trial involved just twenty-nine patients, but results were promising. Data indicated consistent benefit to patients three years after the initial surgery. Crucially, the treatment isn’t just slowing symptoms, but there is also evidence it helped to preserve brain tissue. Markers of neuronal death in spinal fluid, which would typically increase as Huntington’s disease progresses, were actually lower than before treatment in study patients.

The therapy isn’t without complications. Beyond the complicated and highly invasive brain surgery required to get the virus where it needs to go, some patients developed inflammation from the virus causing some side effects like headaches and confusion. There’s also the expense — advanced gene therapies don’t come cheap. However, on the positive side, it’s believed the treatment could potentially be a one-off matter, as the brain cells that produce the critical microRNA fragments are not replaced regularly like other more disposable cells in the body. While it’s a new and radical treatment, pharmaceutical company UniQure has plans to bring it to market as soon as late 2026 in the US, with the European market to follow.

It’s not every day that scientists discover a new viable cure for a disease that has long proven fatal. However, through genetic techniques and a strong understanding of the causative factors of the disease, it appears scientists have made progress in tackling the spectre that is Huntington’s disease. For the many thousands of patients grappling with the disease, and the many descendents who struggle with potentially having inherited the condition, news of a potential treatment is a very good thing indeed.

Featured image: “Huntington” by Frank Gaillard.

I bet this will have the same fate as the 3 or 4 cancer treatments announced this year and then never heard about. Well hidden in a vault.

That isn’t even a GOOD conspiracy theory…

You obviously have no idea how hard it is to keep a secret.

You also apparently have no idea how much researchers care about the cures they are working on.

The reason you aren’t hearing about those cancer treatments, is that they can’t prove they work.

The announcements were likely overzealous researchers that hadn’t had a good look at the data yet, or worse, marketing blurbs.

It’s also possible that they were just scams to drain more project funding.

Having a working treatment that was secreted away is INCREDIBLY unlikely, to the point where it isn’t even worth considering anywhere but fiction.

There are other reasons for what initially looks like a great cancer treatment to drop from the news.

It takes years to get statistically meaningful results.

It has unacceptable side effects.

It takes a long time to get government approval.

It works on only a few types of cancer.

It works on only a few types of people.

The initial trials were on non-human animals and the treatment doesn’t work on people.

The cancer it was tested against was induced by a specific chemical and doesn’t work on naturally developed cancer.

The cancer it was tested against develops only in the presence of a certain genetic defect, not generally.

Initial testing was in vitro, and is impossible/dangerous/ineffective in vivo.

“I can’t keep a secret so other people with immense wealth and power and incentive also can’t keep a secret”

lol. Lmao, even.

Crypto AG comes to mind as an example of a secret very well kept for generations. My money is on Tor being the updated digital version of Crypto AG, with a mathematical backdoor that nobody has really bothered to find yet.

Tor doesn’t need a mathematical backdoor. Tor failed to grow beyond a nation-state’s ability to own a majority of edge nodes. I want to say nearly ten years ago, the monthly cost to own enough machines to control the majority of the edge nodes of Tor was between $1 and $2 million/month. People didn’t think that it had happened yet, but they weren’t sure and it was assumed that the payoff rate was likely to be the only reason it hadn’t been done earlier.

So, as long as the Tor network remains small enough, swamping it with honeypots so all of the traffic either starts or ends some place you control allows you to deanonymize traffic and find sources and destinations.

“announcements were likely overzealous researchers”

overzealous PR departments for universities/companies

The researchers know what stage of development things are at, the PR people don’t.

It’s not going to be hidden in a vault. However, it might not become widespread because right now (as described in TFA) it involves injecting custom DNA strands into the brain of a patient in an operation that takes most of a day. That’s just not a viable treatment for the vast majority of patients.

Hopefully* this is just the first breakthrough, and in the next few years the treatment can be refined to be cheaper, and easier to administer, but we’ll have to wait and see.

The reason you hear about cancer ‘treatments’ that never go anywhere, is because of over-enthusiastic PR departments over-hyping research which is still at a very early stage.

*one of my best friends has recently been diagnosed with Huntingdons, so I care a lot about this.

Less that cures are successful and then hidden in a vault, more that cancer and other tragic diseases are like a magic money printer when it comes to research grants. Nobody wants to be seen as not wanting to help kids with cancer. If you’re working on some new chemistry or medical gizmo that you need a bit more runway on, just mumble something about cancer or Alzheimer’s or a few other limelight diseases and you can pretty much get what you need. But cancer is hard. It basically describes a fundamental fault mode of every single cell of every tissue in your body in a million different ways. There’s no cure for cancer.

The truth is more tragic and banal than the X-Files most of the time.

This right here is why I am fully on the “For Profit” healthcare side. The amount of cost to figure this out, test and bring to the market…. It wouldn’t happen without the chance to profit. No profit = no investors = no research.

Waiting for “But the EU” yea, drugs aren’t developed with the EU in mind they are developed with the for profit US market in mind.

I say this as someone that takes a biologic which is also expensive, complex and wouldn’t exist without profit. Been on one for more than a decade, and its not a problem in the US. 10 min conversation and I leave with a prescription. The place I am in the EU required government approval, despite me having private insurance, and the Dr was concerned my condition “wasn’t bad enough”.

Literal craziness

Acting as if the entire EU has the same process is also literal craziness, as is stating this without acknowledging downsides of for-profit healthcare. I’ll have my takes with a solid portion of nuance, please.

Germany. The richest country in the EU, trying to decide if my crippling pain after not having my meds for 8 months (because Germany) is “bad enough” for a drug that costs them nothing (private insurance) and that I have extensive history with (3 years on this particular one).

Now imagine what a poorer country in the EU would do..

How about Canada tracking “preventable deaths” caused by their own healthcare system?

The downside to for-profit is obviously the costs. Its the classic engineering dilema “Good, Cheap, Fast, pick any two”.

I would rather have stuff like custom viruses implanted in my brain and biologics available and accessible than a “well sucks to be you, go home suffer, and die”.

One of the downsides of national resting scowl face.

Nobody can tell if you’re in actual pain.

Not going to tell them, that would be showing weakness.

Upside, cheap good beer.

A case of Becks (Made in St Louis) costs $30 in the USA?

Need an extra six to equal a German crate.

Robbery.

On the other hand, you can’t find decent Tequila in Germany.

Just Patron.

Also all food incredibly bland…but some really good…mostly pork bits.

Then again, Christmas market bacon cake and awful hot mulled wine…

Worse than Jell-O salad at Mormon picnic, but at least slightly drunk.

Nobodies ever heard of Irish coffee in Germany.

That’s the final decider.

Dual citizenship is academic, can’t live there.

Also relatives…Love them, but better from California.

Agree, beer is good and the food is bland (aside from doner.. Germany tries to claim it but its not really German)

Hadn’t heard of the bacon cake, I’ll have to try it. The Shinken Kase pretzels are pretty good though.

Doner is just a Gyro.

It’s not even Turkish, it’s Greek.

(Ducks and serpentine runs for exit).

The only difference is an electric buzzer vs a sharp knife.

Sometimes pork in the meat.

I’d skip the bacon cake.

I assumed they had fried the bacon first, nope,

Much too much fat.

Also WTF is up with ‘curry wurst’?

Awful.

I’m surprised an Indian person hasn’t nutted up, screaming.

Even Thai restaurants in Berlin are bland.

I don’t know what biologic you are on but if you think ANY drug was developed entirely, or even mostly with private money you are totally off your head. All the basic research is funded by public money, or some large charities, Wellcome and Howard Hughes Medical Institute being by far the biggest. Once the basic science has progressed far enough the private companies pick up the public research, sometimes licensed but mostly not, and move towards a profit when enough of the hard very expensive background slog has been done.

Source, because you are painting with extremely board brush strokes that are highly doubtful.

Note to HaD editors- please include link to announcement, press release, medical

Literature citation etc. without it it’s hard to fact check and also it’s, um, kinda plagiarism, if you don’t cite sources. Sorry if it’s there somewhere and I just missed it. Thx

I don’t think writing about somebody else’s writing quite counts as plagiarism, even if it’s not cited properly.

I’m obviously not an expert but I thought the key thing with CRISPR was its ability to precisely edit DNA.

Why could it be rigged to just chop off the extra repeats in the DNA itself?

I am not a geneticist, but two possible reasons come to mind: CRISPR does not have any kind of logic in it, so there’s no memory to keep a counter in to figure out which repeats are deleterious. CRISPR may have a limit to the number of base-pairs that can be carried and placed correctly. Cutting out the section with extra repeats and replacing it with >26 CAG repeats may not work with natural skulls.

I’m not a geneticist, but my understanding is that (as Bear Naff suggested), that there would be a risk of removing an arbitrary number of CAG repeats, and that the biological roles of huntingtin are poorly understood outside of some aspects of embryonic development and cell survival, you might end up with an equally, or even less functional gene if you go in the other direction. I’d guess the main issue is that you’re introducing a double strand break for which the repair mechanisms have inconsistent outcomes. I can’t remember if neurons have the full range of somatic cell repair mechanisms, but they can do Non-Homologous End-Joining, and that tends to produce quite a lot of point and frameshift mutations.