Although the humble propeller and its derivatives still form the primary propulsion method for ships, this doesn’t mean that alternative methods haven’t been tried. One of the more fascinating ones is the magnetohydrodynamic drive (MHDD), which uses the Lorentz force to propel a watercraft through the water. The somewhat conductive seawater is thus the working medium, with no moving parts required.

Although simple in nature, only the Japanese Yamato-1 full-scale prototype ever carried humans in 1992. As covered in a recent video by [Sails and Salvos], the prototype spent most of its time languishing at the Kobe Maritime Museum, until it was scrapped in 2016.

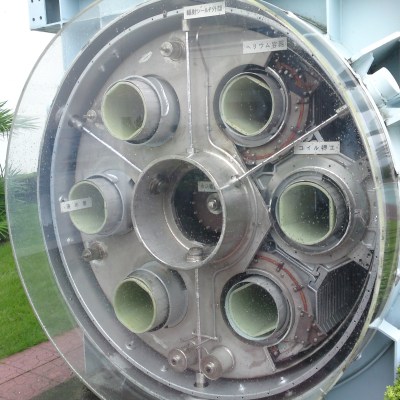

There are two types of MHDD, based around either conduction – involving electrodes – or induction, which uses a magnetic field. The thrusters used by the Yamato-1 used the latter type of MHDD, involving liquid helium-cooled, super-conducting coils. The seawater with its ions from the dissolved salts responds to this field by accelerating according to the well-known right-hand rule, thus providing thrust.

The main flaw with an MHDD as used by the Yamato-1 is that it’s not very efficient, with a working efficiency of about 15%, and a top speed of about 15 km/h (8 knots). Although research in MHDDs hasn’t ceased yet, the elemental problem of seawater not really being that great as the fluid without e.g. adding more ions to it has meant that ships like the Yamato-1 are likely to remain an oddity like the Lun-class ekranoplan ground effect vehicle.

For as futuristic as this technology sounds, it’s suprisingly straightforward to build a magnetohydrodynamic drive of your own in the kitchen sink.

Thanks to [Stephen Walters] for the tip.

What!? No reference to The Hunt for Red October!!

Exactly. The “caterpillar” on the Red October. My first thought too.

This tech is old. We already have efficient MHDD only not for commercial use. Like the “Raxial” motor. Something like that but with more coherent streams.

it’s mentioned in the video.

One ping only, Vasiliy.

“it would sound like whales humping or a seismic anomaly. But speed it up 10 times, that’s gotta be man made”

Aye, Aye, skipper, but why do you speak Russian with a Scottish accent?

Because of the single malt wiskey.

Twice

Mosht thingsh in here don’t react well to bulletsh.

Accent is spot on.

The Red October is purely fictional submarine

Yes, way too big inside for a submarine! It looked like …a sound stage….hmm mm

No reference either to the Oregon in the Clive Custer novels.

That’s exactly what came to mind was the Oregon ship under Clive Custer authorship. the fictional Oregon was around years ago.

I also thought of Hunt for Red October.

So many things from Hollywood are actually just brought about by writers who are staying in touch with the current applications and views of science.

Speaking of which this also should make you think about… USOs

And as far as the thinking man goes.

It’s Watts not amps or volts neither are good all by themselves.

The US has a sub that has this technology. The USS Wyoming. Based in Pearl Harbor. Moves from Norfolk to Pearl December ’24.

The book version wasn’t as fancy as the movie version. It was pump jets pumping water down long tunnels.

Wouldn’t a combination of these plus a standard propeller would give better efficiency than any of those only?

Standard desiel thrusters are also more efficient than these

Why would you think that?

It almost never works that way.

You’d just kill the props efficiency with complications.

Alternatively perhaps the process could be reversed and used to generate power using a tidal current and a conducting loop?

If a standard propeller is much more efficient than MHDD in the forward process, it stands to reason that a standard turbine will be much more efficient than MHDD in the reverse process.

Yeah, was my thought as well.

Today’s young people…absolutely no culture at all… ☺

Was meant as a reply to irox’s ‘The Hunt for Red October’ comment.

I wonder if the efficiency could be improved by adding large amounts of sodium hydroxide to the water ahead of the intake.

How much would you need to carry, how long would it last and what would the environmental effects be? Not saying it’s a bad idea just wondering about down stream (pun intended) effects.

That’s a reasonable point, the drag from carrying it might cause the efficiency gains to get eaten up.

As someone who experiments with MHD, I am heartbroken that this ship was scrapped.

… Or maybe the brine from desalination would be treatable/useful as a “fuel”

Making our water acidic, thereby killing humans because of a ship

Sodium hydroxide is the opposite of an acid.

Efficiency is extremely poor

Heating, electrolysis, and corrosion dominate

Still useless for propulsion or large-scale pumping

Good idea but concentration would need to be at least 1% in seawater to boost conductivity significantly. So a vessel would need to carry a lot of liquid caustic soda (50% NaOH) to run just a short distance. Also as caustic soda mixed with seawater it would leave a white trail of MgO from reaction with high magnesium levels in the ocean.

Damn, thanks for identifying the drawbacks.

They could call it “The Drano Volcano!”

One ping only.

Oh what the hell, give it a pong as well.

Dint worry; I caught the subtle reference – was already thinking back to October… 😁

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jr0JaXfKj68

In the 1970’s there was an anime series with the Space Battleship Yamato with the “wave motion engine”. It seems art meets life.

That was Starblazers. I watched it every day after school.

Thank you! I’ve been trying to remember the name of that cartoon for 20 years. Lol

There’s a third option, since water is slightly diamagnetic. You can squeeze water out of a tube with a traveling magnetic wave, made by switching coils or physically moving strong magnets around the tube, because the water wants to move from an area of high field density to an area of low field density. It is slightly repelled by magnetic fields, so it gets pushed along.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zy8qh_B8AmI

snort

Diamagnetic force in water is a fantastically weak effect, requiring enormous field gradients to provide even miniscule forces (rather, pressures).

In principle you could do it with simple switched short solenoids, but it would burn a terrific amount of power, even if you were to use superconducting coils.

I’d love to see the efficiency figures.

If the effect could produce significant force you wouldn’t be able to push a human bag of mostly-water into a magnetic resonance imaging system: the field gradient at a MRI system bore entry is around 1 T/m. It acts to push water out of it, but very, very weakly.

True, but it would still work. You can levitate a frog because the water in its body is repelling the magnetic field.

It would work better if you had two materials with different magnetic permeability, like water and air, like in the demo video. If you make bubbles in the tube, the bubbles would displace the water much more than the magnetic field itself would.

I’m not convinced it would actually work at all: water exiting the gradient field will need to be replaced by the same volume of water entering the gradient field: The parcel being pushed out of the field (“falling downhill”) is replaced by another of equal volume and mass that needs to be pushed into the gradient “uphill”. I can’t come up with a geometry that will produce a net force.

Think of the frog pinned to levitate in the magnetic field “cone”. If you lift the cone up, the frog would follow along.

You’re right if there’s just water everywhere, the forces would cancel out in the static case and there’s no net push anywhere, but when the magnetic field is moving I think it would drag the whole thing along.

What I think would happen, there would be a very very minute density variation in the water subjected to the magnetic field – so the bit in the strongest magnetic field would have less water than the surrounding volume.

So when the magnetic field moves away, that volume shrinks and draws in more water, but then the adjacent area where the magnetic field now is, expands. So there’s a net flow of water in the opposite direction of where the magnetic field is moving.

So if you have the tube surrounded by solenoids switched on and of in a sequence, and you sweep it from one end to the other rapidly and repeatedly, you get an unidirectional flow going. It’s probably going to be extremely weak and require extreme power, but it seems like it would work.

Hot water expands and cold contracts. Plus bubbles would promote the rise. Could you also use the weight of the ship and displacement? The up and down of the waves to “scoop ” the water uphill??

Nice Star Trek reference

This might be fine for passive electrical generation though if the current constantly supplies enough force. Not really on the scale of municipal power production but maybe enough for amenities in isolation.

Oh so this is how nuclear propulsion systems could work on nuclear subs, which don’t have to worry about power efficiency

I love how actual scientist and engineers worked over a long time to produce this prototype, but the commenters here read the article for 2 minutes and are offering ways to improve it. Do you guys ever consider you have no idea what you’re talking about?

It’s not clear who “you guys” is.

We can improve them, we have the technology. All we need is six million dollars.

They should really have let us take a crack at it before they scrapped it. We’re smart. We know words. We know sciencey stuff.

Classic!

ABSOLUTELY NOT !

Sir, this is HaD.

You must be new here.

There’s the coffee, pot, here’s your 555.

Yesssssssss, I’ve always wanted to build a magnetohydrodynamic drive of my own in the kitchen sink!!!

Be careful with that Bill. I tried doing that with a flux capacitor and now the kitchen is gone.

18 comments removed. Someone got a beef about levitating frogs?

Dammit! I was cleaning the grease filters at the soup kitchen and missed the whole thing!

I DO hate it when that happens !

Relatively simple mechanisms, a ‘coating’ of tiny linear motors in an array on the hull, underwater, pulsating in sequence, will act as a wave, producing thrust to propel the vessel. Adding sophisticated sensors to detect impinging ocean waves to provide feedback to the motor arrays can be used to maximise the net energy transfer.

Obviously, storm conditions, when ocean waves are likely to be more random will introduce a lot of complication, but this is actually where a larger hull can be more consistently energy efficient.

Since the effective hull, the outer surface of a huge array of motors, is fully in the water, the central section along the keel can be used to add a row of motors fore to aft that acts as a centreboard, multiplying the efficiency and stability of the vessel moment to moment.

A possible unexpected benefit might be a reduction in the incidence of barnacles, which is a good thing to study in a test vessel.

Reminds me of Seauquest Dsv vessel!

Bad name for a vessel. The Yamato was the name of Japan’s newest and mightiest battleship in WW2. It went against the American Navy and became the world’s newest and mightiest coral reef.

Where might I find that particular “reef” on Google Earth?..

It’s around 30° 22′ N, 128° 04′ E. It’s under several hundred meters of water, so you won’t see anything on Google Earth.

*NaK alloy

Build it and they will come. My favorite line… take it to Carderock Navel Base. College competitions every year, end up there. Silent propulsion sounds like a great oportunity to expand our knowledge base on the subject. Where there is a need, it will be done.

The Robotics club in my neighborhood has proven that. Simple task built by high-school students. The next gen and their abilities of commanding the next gen of tools is amazing.

Those numbers sound pretty low in the spectrum of efficiency on the Magnetohydrodynamic.

The power of a Whale tail have me impressed, and thinking there are other ways to move silently. As Bruce Lee once said, “move like water”. I cant think of anyone more fluid than he.

My last dive with Whales proved that 20 to 40 foot bounce in the water at 200 feet out from my observance, and a small movement of the Whale tail. Proves that we have not even begun to tap whats possible in fluid dynamics. Those animals are amazing. I say look to nature with what has already been created. I would love to go in that direction for a build. This sound like a valuable fun exploration subject.

Why do we limit thinking about a tiny submersible propulsion, when we can do better. Like building and finding a proper propulsion system for a Dyson sphere built around the entire solar system (we need storage space for when we travel, also Jupiter has some gas for the cars, smaller planetoids got ice/water, etc).

I understand that when it was running it sounded like whales humping