Making a truly flat surface is a modern engineering feat, and not a small one. Even making something straight without reference tools that are already straight is a challenge. However, the ancient Egyptians apparently made very straight, very flat stone work. How did they do it? Probably not alien-supplied CNC machines. [IntoTheMap] explains why it is important and how they may have done it in a recent video you can see below.

The first step is to define flatness, and modern mechanical engineers have taken care of that. If you use 3D printers, you know how hard it is to even get your bed and nozzle “flat” with respect to each other. You’ll almost always have at least a 100 micron variation in the bed distances. The video shows how different levels of flatness require different measurement techniques.

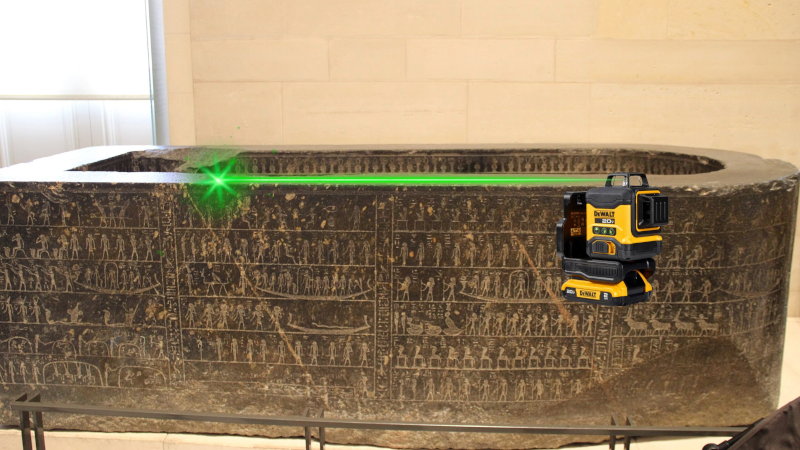

The Great Pyramid’s casing stones have joints measuring 0.5 mm, which is incredible to achieve on such large stones with no modern tools. A stone box in the Pyramid of Seostris II is especially well done and extremely flat, although we can make things flatter today.

The main problem with creating a flat surface is that to do a good job, you need some flat things to start with. However, there is a method from the 19th century that uses three plates and multiple lapping steps to create three very flat plates. In modern times, we use a blue material to indicate raised areas, much as a dentist makes you chomp on a piece of paper to place a crown. There are traces of red ochre on Egyptian stonework that probably served the same purpose.

Lapping large pieces is still a challenge, but moving giant stones at scale appears to have been a solved problem for the Egyptians. Was this the method they used? We don’t know, of course. But it certainly makes sense.

It would be a long time before modern people could make things as flat. While we can do even better now, we also have better measuring tools.

I’m not saying it was aliens.

…but it was aliens.

Oh come on, someone had to say it.

That blue stuff is called Prussian blue. The tricky part there, and maybe someone more machine shop oriented than me can correct me is, you still need a reference flat.

It’s hard to think about ancient processes that could afford a flat surface being honest. All I can think of is a large vat of water or oil

Assuming the meniscus was flat enough. half the challenge there would be ensuring whatever was dropped on it was dropped true.

Fun to think about.

That blue stuff is indeed called a lot of things, including Prussian Blue, as it was at one point made with actual Prussian Blue (the chemical/dye) suspended in oil. But the modern formulations, even if they’re called “prussian blue”, are usually made with other dyes or pigments (most commonly gentian violet, I believe, just to be confusing).

In the circles I know, it’s usually referred to as “dykem”, which is a brand that essentially became the kleenex of blue marking dyes.

Okay I had an idea. If you had a fat and a big pool of water. You could make one side flat by letting it solidify on top of a tub of water if you were very careful

“All I can think of is a large vat of water or oil” Ice.

Am I the only one who associates Prussian Blue and cyanide?

Are you thinking of Paris Green and arsenic?

No, but I did see that episode of Doc Martin. Typically, iron(II) sulfate is added to a solution suspected of containing cyanide, such as the filtrate from the sodium fusion test. The resulting mixture is acidified with mineral acid. The formation of Prussian blue is a positive result for cyanide.

You don’t need a flat to begin the process, but you need three surfaces.

It’s called the Whitworth three plates method, and with 2 plates you can get the surfaces to match, but they might be concave or convex (but the same, to a high degree of accuracy). When you go to three plates you can get optically flat surfaces.

https://ericweinhoffer.com/blog/2017/7/30/the-whitworth-three-plates-method