It was January 25th of 1979, at an unassuming Michigan Ford Motor Company factory. Productivity over the past years had been skyrocketing due to increased automation, courtesy of Litton Industry’s industrial robots that among other things helped to pick parts from shelves. Unfortunately, on that day there was an issue with the automated inventory system, so Robert Williams was asked to retrieve parts manually.

As he climbed into the third level of the storage rack, he was crushed from behind by the arm of one of the still active one-ton transfer vehicles, killing him instantly. It would take half an hour before his body was discovered, and many years before the manufacturer would be forced to pay damages to his estate in a settlement. He only lived to be twenty-five years old.

Since Robert’s gruesome death, industrial robots have become much safer, with keep-out zones, sensors, and other safety measures. However this didn’t happen overnight; it’s worth going over some of the robot tragedies to see how we got here.

Just Following Orders

Perhaps the the most terrifying aspect about most industrial robots is that they are fairly simple machines, often just an arm containing a series of stepper motors and the electronics that strictly execute the tasks programmed into it when the manufacturing line was designed and assembled. This means a large metal arm, possibly weighing more than an adult human, that can swing and move around rapidly, with no regard for what might be in between its starting and end position unless designed with safeties in place.

This is what led to the death in 1981 of another factory worker, Kenji Urada, a maintenance worker, who was trying to fix a robotic arm. Although a safety fence had been installed at this Japanese plant that would disconnect the power supply of the robot when this fence was unhooked, for some reason Kenji decided to bypass this safety feature and hop over the fence. Moments later he would be dead, crushed by the robotic arm as it accidentally was activated by Kenji while in manual mode.

During the following investigation it was found that Kenji’s colleagues were unfamiliar with the robot’s controls and did not know how to turn it off by simply opening the fence. Subsequently they were unable to render him any aid and were forced to look on in horror until someone was able to power down the robot.

A similar accident occurred in the US in 1984, when a 34-year old operator of an automated die-cast system decided to cross the safety rail around the robot’s operating envelope to clean up some scrap metal on the floor, bypassing the interlocked access in the safety rail. In this case it wasn’t the arm that crushed the worker, but the back end, which the worker apparently had deemed to be ‘safe’. He had received a one-week training course in robotics three weeks prior.

Protecting Squishy Humans

When it comes to industrial robot safety rules, we have to consider a number of factors beyond the straightforward fact that getting crushed by one is a scenario that a reasonable person would want to avoid. The first is that industrial robots are quite expensive, which makes adding major fencing and other safety measures not much of a financial issue in comparison.

The second factor is that while humans are really quite versatile, they tend to have the annoying habit of bypassing safeties despite endless briefings and drills that are designed for their own protection. Let’s call this factor “human nature”. Kenji Urada’s gruesome death is an example of this, but other industries are rife with examples too, giving agencies like the US Chemical Safety Board a seemingly endless collection of safety rule violations to investigate and condense into popular YouTube videos of disaster sequences.

The final, third factor that ties all of this together is that we no longer live in the early decades of the Industrial Revolution, where having a human worker getting caught with an arm between some gears, or crushed by a mechanism would only lead to some clerk rolling their eyes, crossing out a name and sending out an errand boy to post a fresh ‘help wanted’ note.

Ergo, we needed to find ways to human-proof industrial robots against humans and protect us against ourselves.

ISO 10218

Although some nations have their own standards, the overarching international standard is found in ISO 10218, currently in its 2025 update. This standard comes in two parts, ISO 10218-1, which concerns itself with the robot’s individual parts and targets robot manufacturers, as well as ISO 10218-2, which looks at complete systems and the integration of robots.

There are a number of distinct types of hazards when it comes to working around industrial robots, the most obvious of which is the crushing hazard. To prevent this and similar hazards, we can install plentiful of safety fencing to ensure that the squishy human cannot get within the range of the unsuspecting robot.

In the case of an especially persistent human, or potentially a legitimate human maintainer or operator, it’s crucial to ensure that the robot is powered down or rendered harmless in some other way. For example, the safety fence that should have prevented Kenji Urada from losing his life was designed for this, but unfortunately could be bypassed.

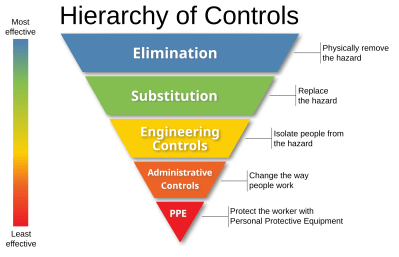

Similarly, in the case of Robert Williams there was a tag in/tag out system in place for the robotics, but Robert had not been instructed in this and apparently unaware of the dangers. Being able to bypass such safeties gets us firmly sliding down the rabbit hole of the hierarchy of controls.

Similarly, in the case of Robert Williams there was a tag in/tag out system in place for the robotics, but Robert had not been instructed in this and apparently unaware of the dangers. Being able to bypass such safeties gets us firmly sliding down the rabbit hole of the hierarchy of controls.

The most effective hazard elimination is basically that, but since the robots are rather needed, and we got no replacement for them other than forcing the humans to do all the work again, this step is no real option here.

Next we can try to make robots safer, by adding intrusion detection sensors to the robot’s hazard zone, or as Amazon trialed in 2019 by making the squishy humans in its warehouses wear a device that alerts the robots around them on the warehouse floor of their presence without relying on either machine vision or obstacle recognition.

The placing of physical barriers is next, as part of engineering controls. This effectively tries to prevent humans from wandering into the danger zone like a particularly big fly around a brightly lit up bug zapper. Theoretically by putting a sufficiently daunting barrier between the hazard and the worker will said worker not end up facing their doom.

In an ideal world this would be all that it’d take to guarantee a completely safe work floor, even in the case of some distracted wandering. Of course, this doesn’t help much if said robots are sharing a warehouse floor with humans. To patch up the remaining gaps we got safety training courses as part of the administrative controls, but if these were very effective then the USCSB would already be mostly out of a job.,

The final item in the hierarchy of PPE can easily be skipped in the case of industrial robots, other than perhaps steel-tipped boots, a hard-hat and safety glasses in case of dropped items and flying debris. If an industrial robot’s arm is headed your way, there’s no PPE that will save your skin.

The Future

At this point in time industrial robots are fairly safe from humans, though in the US alone between 1992 and 2015 at least 61 people died due to sharing the same physical space with such a robot or a similar unfortunate event. As the number of robots increases in industry, but also in construction and health care, the topic of safety becomes ever more important.

In the case of a stationary industrial robot it’s fairly easy to just put a big, tall fence around it, lock the only gate and force anyone who absolutely needs access to beg an audience with the maintenance chief. In the case of the thousands of robots rolling around in warehouses like Amazon’s, situational awareness on the part of the robots can help them detect and avoid obstacles.

As long as humans are more fragile and weaker than the robots that they find themselves working around, it’s probably reasonable to expect said humans to pay a modicum of respect to the Death Machine, as the engineers who built them can only add so many technological solutions to what ultimately ends up being a game of idiot-proofing. Because absolutely nobody would ever do these exact things to willingly endanger themselves and/or others.

And yet, you still see people doing stupid stuff in factories. A while ago, I worked in the summers as a student worker in a metal factory, putting pieces in a machine that would cut them or solder them with a laser etc While I was working there, people would tell me about accidents that happened in that factory, one, a metal sheet drum fell while it was being loaded by an automated system on top of the legs of a worker. He died. The thing is he shouldn’t have been near it

Another story I was told, is that some guy had to do some maintenance inside the machine, and activated the manual mode of the laser robot. He didn’t notice that the speed was set to high, and crushed his own skull.

One could think, no way this happened, but while I was working there I saw my chief going into a machine that was giving problems, and hold a metal plate on front of the laser while putting the other hand over his eyes to cover them from laser radiation and ordered the line worked to press start

There where safety systems in place in these machines. The machines where quite modern. It was just that the wrong people had access to the keys that would disable the safety systems

Ah, yeah, I almost forgot. These machines have a system that sucks the air and filters it, to suck all the fine metal dust. This dust is extremely dangerous for humans, it can burn, it is really bad for your lungs and it icks and burns like hell in the skin. Workers need a special training and special PPE to clean the filters and empty the bucket where the metal dust goes. Well, I, just a normal student that was working for just 10 weeks a year there with no special training, was ordered to clean those filters and empty the bucket while the supervisor was watching from 5 meters away…

I worked there not even 10 years ago

I forgot to say, that while other workers did the cleaning with the special PPE, that was like a suit and a mask with positive airflow, I was asked to do it with just a pair of latex gloves and a normal mas that you can buy for 5 € in a homedepot

Idiot proofing only works until the system is tested by a more clever idiot.

Amen to that. It applies to computer users also.

It’s a common expression, but systems build for functional safety should not just fail safely and redundant, it is also required to make it very difficult to use unsafely. This goes for gate sensors with encrypted links, optical fences, lock-out-tag-out locks, etc.

Safety culture is site specific.

I worked at a couple industrial labs and several academic labs.

On the one, great, end there was only one entrance to the labs right by the secretary desk. If you walked in with anything bless than perfect PPE it would be treated as if you shoes up to work with no pants. Like- confusion. The safety culture was very strong and non judgmental. Lapses happen and everyone would be like “hey bob you shouldn’t be doing that” and bob would say “oh shoot thanks!”

Other end of the spectrum different lab (academic) if you pointed out dumb stuff they treated you like a Narc. I saw the summer intern lock himself in the liquid N2 filling room in shorts and flip flops, no face protection, and one oven mitt. Fortunately they weren’t jerks when poi ted it out hit the level of cluelessness was astounding.

Many, many more examples over the last 30 years or so of lab work but you get the idea.

There’s a great story about workspace safety issues in each episode of a podcast ‘Well, There’s Your Problem’. It really makes you wonder how creative and reckless some humans are.