Last week, I wrote about cargo culting in a much more general context, so this week I’m going to come clean. The file that had me thinking about the topic was the worst case you’ve probably ever seen: I have a .emacs file kicking around that I haven’t really understood since I copied it from someone else – probably Ben Scarlet whose name is enshrined therein – in the computer lab in 1994! Yes, my .emacs file is nearly 30, and I still don’t really understand it, not exactly.

Now in my defence, I switched up to vim as my main editor a few years ago, but this one file has seen duty on Pentiums running pre-1.0 versions of Linux, on IBM RS/6000 machines in the aforementioned computer lab, and on a series of laptops and desktops that I’ve owned over the years. It got me through undergrad, grad school, and a decade of work. It has served me well. And if I fired up emacs right now, it would still be here.

For those of you out there who don’t use emacs, the .emacs file is a configuration file. It says how to interpret different files based on their extensions, defines some special key combos, and perhaps most importantly, defines how code syntax highlighting works. It’s basically all of the idiosyncratic look-and-feel stuff in emacs, and it’s what makes my emacs mine. But I don’t understand it.

Why? Because it’s written in LISP, for GNU’s sake, and because it references all manner of cryptic internal variables that emacs uses under the hood. I’m absolutely not saying that I haven’t tweaked some of the colors around, or monkey-patched something in here or there, but the extent is always limited to whatever I can get away with, without having to really learn LISP.

This ancient fossil of a file is testament to two things. The emacs codebase has been stable enough that it still works after all this time, but also that emacs is so damn complicated and written in an obscure enough language that I have never put the time in to really grok it – the barriers are too high and the payoff for the effort too low. I have no doubt that I could figure it out for real, but I just haven’t.

So I just schlep this file around, from computer to computer, without understanding it and without particularly wanting to. Except now that I write this. Damnit.

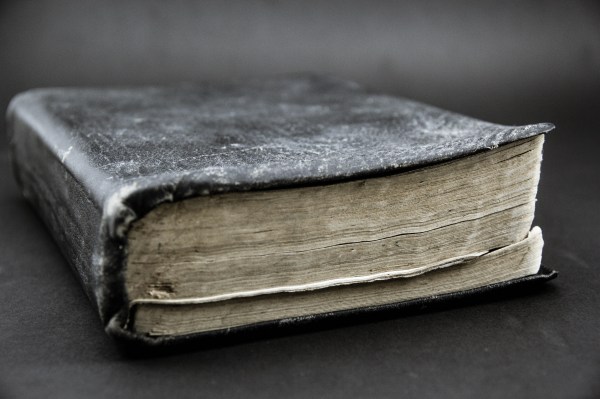

Featured image: “A Dusty Old Book” by Marco Verch Professional.