It is said that the first casualty of war is the truth, and few wars have demonstrated that more than World War II. One scientist, whose insights would make the atomic age possible, would learn a harsh lesson at the outset of the war about how scientific truth can easily be trumped by politics and bigotry.

Lise Meitner was born into a prosperous Jewish family in Vienna in 1878. Her father, a lawyer and chess master, took the unusual step of encouraging his daughter’s education. In a time when women were not allowed to attend institutions of higher learning, Lise was able to pursue her interest in physics with a private education funded by her father. His continued support, both emotional and financial, would prove important throughout Lise’s early career.

In 1905, at the dawn of a century that would become dominated by total war, Lise became only the second woman to take a doctorate degree from the University of Vienna. She began to realize the degree to which her pursuit of the truth was going to be complicated by her gender. Traveling to Berlin, she sought to attend Max Planck’s theoretical physics lectures. Initially hostile to having a woman in his lectures, Planck eventually relented, and by 1912 he was such an enthusiastic supporter of Lise that he appointed her his assistant, which led her first paid job in physics.

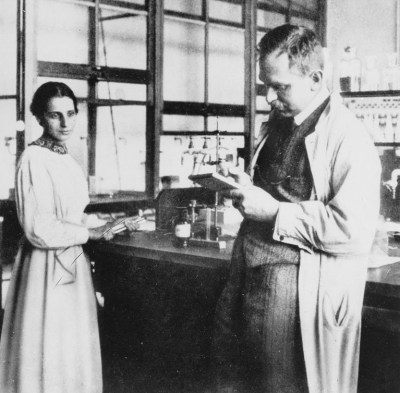

In Planck’s lab, Lise met Otto Hahn, a German chemist with whom she would partner to explore the relatively new field of nuclear chemistry. Still an outsider, she and Otto were forced to work in a basement shop with orders that she not show her face above ground, so as not to scandalize the men.

Despite this handicap, the team of Meitner and Hahn was very productive. Her physics complemented his chemistry well, and by the time World War I broke out in 1914 they had already discovered several new radioisotopes. The war hindered their efforts but did not stop them. Otto had been assigned to a German gas warfare division; Lise was volunteering with an army X-ray unit. Whenever they could get leave at the same time they would get together to work on experiments.

A Ring and a Prayer

In a period of changing attitudes between the wars, Lise was finally allowed out of her basement labs and eventually became the first woman in Germany’s history to be named a full professor. She also became a department head by 1935, but by then war was again brewing. Adolf Hitler had come to power in 1933 and began his purge of Jews from academia. Lise, with her Jewish heritage, knew she was at risk, but as an Austrian citizen was protected from Nazi racial laws, and ignored the warning signs.

By 1938 and Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria, it became clear that Lise was in danger, and plans were hastily assembled to get her to safety. Otto helped her pack for what would be a perilous trip to Holland without a valid passport, giving her a diamond ring that she could use as bribery at the border. Luckily it wasn’t needed – she made it safely into Holland and eventually to Sweden, never to return to Germany. She got a post in Stockholm and restarted her life’s work in exile.

The 1930s were an exciting time in nuclear chemistry. The neutron had only just been discovered, and researchers were eagerly using it to probe the structure of the nucleus. It was once thought that bombarding heavy elements with neutrons could only produce new, heavier elements, and radiochemistry labs around the world were gleefully shooting neutrons at whatever targets they could find. But experiment after experiment with heavy elements yielded a puzzling result: lighter elements were appearing rather than yet heavier elements. Nobody could make sense of this: how could adding massive neutrons result in light products instead of heavier ones?

Back in Berlin, Otto Hahn and his new partner, Fritz Strassman, had uranium in the target block of their radium-salt and beryllium powder neutron source, and they undertook careful chemical separations of the products. At first, Hahn was convinced that they had produced radium, but after continued and increasingly purer chemical separations it was clear that barium was being produced. Radium could be explained – the loss of two alpha particles from uranium, atomic number 92, could result in radium, atomic number 88. But barium, at atomic number 56, was only a little over half uranium’s size. What could possibly be going on?

A Walk in the Woods

Nothing in Hahn’s chemical background could explain what he was seeing. He needed a physicist’s take on his data, so he posted a letter to Lise Meitner in Stockholm with his puzzling results. It was December of 1938, and Lise ruminated on Hahn’s results during her Christmas vacation with her nephew, the physicist Otto Frisch, also forced to emigrate from Germany. They excitedly discussed Hahn’s letter during a walk, trying to come up with an explanation for the barium.

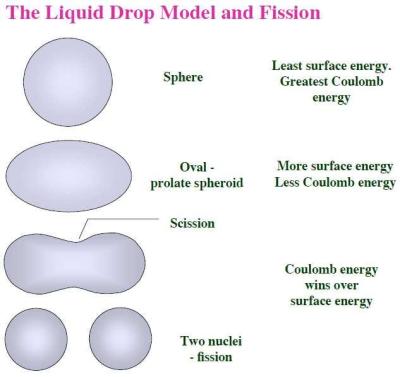

Lise and her nephew sat on a log and sketched out mechanisms, imagining the uranium nucleus as a wobbly, barely stable sphere. A neutron striking such a target would add energy that would start an oscillation and randomly elongate the nucleus. Eventually, the strong nuclear force, which acts only at short distances and holds the nucleus together, would be overcome by electric repulsion of the two ends of the lengthening nucleus. A waist would form in the nucleus, which would now take on a dumbbell shape. The strong nuclear force would again become dominant in each end, and two new, stable nuclei would pinch off.

Lise immediately realized that the two nuclear fragments, barium and krypton, would be forced apart with tremendous energy by mutual repulsion – a quick calculation showed it would be 200 mega electron volts from a single uranium nucleus – enough to visibly moved a grain of sand! In the course of their walk in the woods, aunt and nephew not only provided the theoretical underpinnings of what Hahn had observed but also explained why no elements past uranium could exist naturally.

Publish and Perish Anyway

With observations and explanation in hand, a flurry of papers was published in early 1939. Hahn and Strassman published their barium results and quickly followed up with an explanation based on Lise’s insights, which she had discussed with him after her walk with Frisch. Shortly thereafter Meitner and Frisch published their results, which Frisch had just confirmed experimentally. The three papers electrified the radiochemistry community and became the basis for all that was to follow in the turbulent 1940s, starting with Einstein’s famous letter to FDR that kicked off the Manhattan Project and ending with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Of the authors of those papers, only Otto Frisch, who had coined the term “fission” after discussions with a microbiologist, would go on to work directly on the bomb; Lise Meitner was offered a job at Los Alamos but refused, saying that she’d have nothing to do with building a bomb.

In 1945, Otto Hahn was notified that he alone would receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of nuclear fission. No mention was made of Meitner and Frisch’s contribution, nor Strassman’s for that matter. Much has been made of the snub, with understandable assumptions of sexism and politicization behind the decision to honor only Hahn. But once the Nobel committee records were unsealed in the 1990s, it became apparent that the chemists reviewing the nominations were ill-equipped to evaluate interdisciplinary work, and just didn’t see the importance of Meitner’s key insights. It’s true that Hahn himself never gave a lot of credit to Lise; in his defense things might have been difficult with his employers had he made it publicly known that he was collaborating with an exiled Jew.

When the political climate was a little more favorable, Hahn tried putting things to right. He himself submitted Lise’s work to the Nobel committee ten times, but she was continually overlooked. Lise Meitner was eventually awarded the Enrico Fermi Prize in 1966 along with Strassman and Hahn. She was also named Woman of the Year in 1946, received dozens of scientific honors, and held many high-ranking posts in the science community. And in perhaps the ultimate honor for a nuclear physicist, element 109 was named “meitnerium” in 1997. It is the only element named after a non-mythological woman.

Despite all that had transpired between them, including some harsh letters from Lise taking Otto to task for continuing to work with the Nazis, they remained close friends for the rest of their lives. Lise died in 1968, shortly after Otto passed. Her tombstone in Cambridge, England simply reads, “Lise Meitner: A physicist who never lost her humanity.”

Dan – You see this is why I love HaD!!! Always a well written article on something interesting. Lise was arguably the FIRST one to actually to pioneer nuclear weapons. She had help but it was mainly her. Even Albert Einstein gave her the respect she deserved. It was lucky Adolph Hitler never got her as he only got Dr. Hiesenburg. But we got lucky in that he stonewalled Hitler with a bogus 1945 roll out date for the first Nazi A-bomb. I guess that would be a better view of the Hiesenburg Uncertainty. (Just kidding!)

A physicist who never lost her humanity. Because, of course, most of them do….

It ain’t easy memorializing someone in a few words. And it’s better than “I’d rather be fission”.

That’s just… beautiful.

So she is the one!

Oh-nine

@Trevor

Did you read the article or are you just responding to the headline? The article specifically discusses one colleague working for the Nazis, and another helping to develop the atomic bomb. The epitaph is a statement–as alluded to in the first goddamn paragraph–about war hijacking physical and intellectual resources of civilizations and turning them towards killing.

Someone reading her epitaph could easily conclude that most physicists lose their humanity. It could have read : “Lise Meitner: A physicist and humanitarian.”

They meant it to read that way.

HAD has a headline writing style that Enquirer style rags would be proud of.

Benchofisms, much as I actually appreciate them in this context, are also spread liberally through the text.

It could have started ‘The best nuclear physicist in the world, of all time, was shunned for being a woman’

> They meant it to read that way.

Who, the people that carved her headstone? It’s her *epitaph*. It’s the text upon her gravestone.

> HAD has a headline writing style that Enquirer style rags would be proud of.

This isn’t HAD title-play, it’s the words that her family chose to remember her.

Oppenheimer never lost his humanity either, since he was able to quote verse 32 from chapter 11 of the Bhagavad Gita (Hindu scriptures): “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”. Just because you are charred on the inside, does not mean you’ve lost your humanity.

I will never forget that, the look in his eyes, the quaver in his voice, and what he must have been feeling.

Thank you for this, I didn’t knew about. Just watched the video and it’s really strong. Seeing him crying is really touching.

“During a meeting at the White House in October 1945, [Robert] Oppenheimer tried to convey his deep moral crisis. ‘Mr. President, I have blood on my hands,’ he remarked. ‘Never mind,’ Truman replied, ‘it’ll all come out in the wash.’ (According to some accounts he offered Oppenheimer a hankerchief.) ‘Don’t you bring that crybaby in here again,’ Truman later told an aide. ‘After all, all he did was make the bomb. I’m the guy who fired it off.’”

Excerpted from The Bomb: A Life (Gerard J. DeGroot, Harvard University Press, 2004, p. 111)

@Truth

I like Bainbridge’s line, “Now we are all sons of bitches.”

Lise Meitner: most definitely NOT a hack.

You are on the wrong site, you should be on hacksaday.com

Whoosh. :)

Tesla’s work was a sham!!! (Thought I’d be the first with that, given the Hedy Lamar comments).

Like my kids say – don’t touch the poop.

You touched the poop, Kent.

They scampered off to Curie land instead.

Ops. Your fridge, washing machine, and air-conditioner motors just died.

Editor: This is my correct email address, not autocorrected…

Okay, I’ll try the original comment again. “Tesla’s work is a sham!!!” Thought I’d be the first given the Hedy Lamarr’s article comments. I got Steve Harveyed by autocorrect before.

“It is the only element named after a non-mythological woman.”

Except for Curium.

Have you ever actually seen her?

I didn’t think so. She’s a myth.

She wasn’t a myth, she was a mythis

They probably say that Curium is named for both of the Curies. Pierre also won a Nobel prize but for some reason he is often forgotten. Since they worked together it only makes sense that Curium would be named in their honor.

Fact is that Curie is the name of Pierre. The name of Marie was Skłodowska. But at that time woman were taken the name of their husband when getting married.

The majority of women in many nations still do.

The element of Curium is named after both Pierre and Marie Curie.

Marie Curie had advocated the activity unit of Curie be a large unit in honor of her late husband, Pierre Curie. As a member of the Radium Standards Committee, Marie used her skills and some bureaucratic tactics in 1921, so that the Committee recommended to the next session of the International Congress of Radiology and Electricity that the curie be defined as the activity of one gram of radium. Whether the Radium Standards Committee (M. Curie, F. Soddy, S. Meyer, O. Hahn, H. Geitel, E. Schweidler, A. Debierne, and A.S. Eve) proposed the Curie unit be dedicated to Pierre, Marie, or both Curies has been debated for many years.

Many say it is both, but no one really knows for sure which Curie it was named after thanks to a bizarre twist of politics way back when:

http://www.orau.org/ptp/articlesstories/thecurie.htm

The whole thing is very Curie-us.

This.

I’ve also been

trying to figure outtoo lazy to look up the mythological woman element. I think it would be cerium, after Ceres, Roman goddess of the harvest.Although she was born into a Jewish family, in 1908 during a visit to home in Vienna, Lise Meitner converted to Christianity, was baptized, and became a Lutheran. She remained a Lutheran the rest of her life. At the time Vienna was primarily Roman Catholic, with restrictions on non-Roman churches (they were not allowed to have steeples or face the main streets). In 1908 Lise’s sisters, Lola and Gisela, were also baptized, but into the Roman Catholic Church.

It’s not clear why Lise became Lutheran, although her mentors in Berlin, Max Planck and Otto Hahn, were Lutheran. And this was all before the rise of Nazism. Of course, even though she had been Lutheran for three decades, Lise’s Jewish ancestry forced her to leave Nazi Germany in 1938.

The National Socialism began before 1900. An intellectual movement away from the churches and to solstice celebrations and “harmless” naturism was combined with ideas from the new philosophers. “Runic” alphabets were invented or meaning assigned to ancient symbols. The swastika was the most popular good luck talisman among German soldiers in WWI, or as their opponents called it, the Great War for Civilization. The NAZI’s leveraged off this movement and swept up the minds of the youth. The rest, as they say, is repeating itself.

Lise Meitner definitely did not make these decision before the rise of Nazism, just a while before NAZI’s gained control.

The Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, commonly referred to in English as the Nazi Party, didn’t become an active political party, and adopt the swastika symbol until 1920. After Hitler was released from prison, the Nazis started to gain political power in 1925, and Hitler became Chancellor in 1933.

It is very unlikely Nazism would have been a factor in Lise’s decision in 1908 to become a Christian and remain one until her death in 1968. In Nazi Germany Meitner was still considered a Jew.

s/Adolph/Adolf/g

No he wasn’t a scientist. Just a mad man.

He was also a shitty artist and mustache aficionado!

Never spit in a man’s face…unless his moustache is on fire!

Yes. It is curious how madmen can sway such a large portion of the population … It’s not like it happened before, or after. Oh wait …

FTFY. Thanks.

Thank you for this article, it’s a pleasure to discover yet another important figure in science in the last century!

I love the first image! Who created that?

That is the work of our art director, Joe Kim.