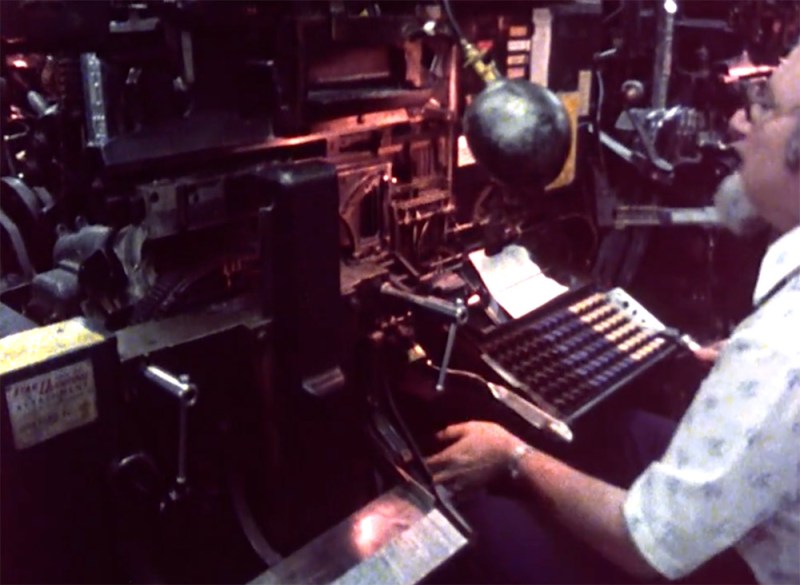

The short film, Farewell — ETAOIN SHRDLU, produced in 1978 covers the very last day the New York Times was set for printing in the old way, using hot metal typesetting.

We’ve covered the magic of linotype machines before, but to see them used as they were in their prime is something else. They saw nearly a hundred years of complete industry dominance. Linotype machines had entire guilds dedicated to their use. Tradesmen built their lives around them. For some of us we see the rise and fall of technology as an expected thing. Something that happens normally, sometimes within spans that cover only a few short years. Yet it’s still a strange thing to see a technology so widely used shut down so completely and relatively rapidly.

To make it even stranger, the computer that replaced the linotype machines is so alien to the technology used today that even it is an oddity. In the end only the shadow of the ‘new’ technologies — showcased as state of the art in this video — are still in use. Nonetheless it’s important to see where we came from and to understand what it means to innovate. Plus, you never know when you see an old idea that’s ready for a bit of refurbishment. Who knows, maybe part of the linotype’s spirit is ready to be reborn, and all it takes is a clever hacker to see it.

Oh, and that title — ‘etaoin shrdlu‘ — is the linotype equivalent of ‘qwerty’. The first two columns of keys on the linotype machine make up those two words.

[via Colossal]

And have you seen one at work? I have…..

I’ve *used* one. As our local daily papers (they shared a production facility) moved to phototypesetting in the 70’s some of the old ones were given to my school districts and ended up in our printing shop class.

Seen one, heck I used to operate one. My family owned a small town newspaper and I got to run the linotype on occasion. These monsters were middlin’ dangerous – if a spaceband hung up, you would get a squirt of hot lead to the face when the line was sent up. Later on, I managed to start my career in computers when a graphucs house in Houston converted to cold type – using the Mergenthaler VIP photo typesetter, an incredible electromechanical gadget, nad a DEC PDP11/70.

I operated one of these too, at a small label and form-making shop that was my first job out of high school. And yep – I got one of those squirts in the face with hot lead.

I love seeing theses “old reportages”

me too, this was a good one. Showed the technology, showed the people, and showed the future… that is already the past.

It is sad to see it go, but I’m sure some hackers will make a clock using the technique.

P.S.: Some weird tags on this article; crt and laser scanner? I still use an ‘old’ tube for the main room and laser scanners aren’t going away anytime soon.

Op, I see the reasons for the tags now. :D

heh all that lead,.. nothing to worry about

lol, didn’t occur to them to also edit the layout on a computer

‘hey bob should we also use the computer to change the layout around?’

‘nah let’s do that by hand and cut and paste everything up the way we want it and then put it through this huge scanner’

‘yeah that sounds easier, let’s do that’

i’m more impressed by the huge scanner than the computer…how did that even work, is it analog and just sent the image electrically to be burned on to the plates,.. there’s no way that was digitally done back then right

Their computers at the time COUDN’T do the layout…GUI’s and laser printers were just being invented in Palo Alto and Rochester. The scanner was a modification of xerography.

You’re expecting WSIWYG in 1978? Remember, the IBM PC and Xerox Star weren’t introduced until 1981, the Apple Lisa not until 1983 and the Macintosh not until 1984. Graphics terminals were expensive and slow. At that time the best you could hope for at the industrial scale needed by the N.Y. Times were character-based terminals connected to the mainframe with symbols to represent layout. I wouldn’t be surprised if those terminals were block-mode and not interactive.

As for the scanner, I’d guess it acted like an analog fax machine. A laser scanner sent an analog stream to a synchronized device that exposed the light-sensitive plastic plates (another scanning laser or CRT.)

WYSIWYG for typesetting existed commercially in 1978, the system I was involved with used 2 terminals per user – a standard text one for data entry, and a secondary Tektronix vector terminal with a longer-persistence phosphor to show the resulting output. It wasn’t as good as came later, of course, but was more useful than raw text.

The whole thing – with multiple users timesharing – was driven by a Data General minicomputer, and output data via mag tape for an RCA Vidcomp phototypesetter (driven by another DG mini, IIRC).

A few years later, even small printing houses had single-user z-80 based workstations with similar capabilities, though the output for those was WYSIWYG on paper strips, which at the shop I saw them at were still laid out on pages by hand.

Mhhhhh….

And what software would you use for the layout?

On what type of terminal?

I’m pretty sure nothing existed at that time. At least for daily edition.

Latex and postscript werent’ really around until the 80’s.

About the linotype, I never realised how hard it was to edit, and print a newspaper.

That’s impressive.

Did any machines use different alloys?

Such as these here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wood%27s_metal#Related_alloys

I can’t seem to find much more info than already mentioned.

Information on type metal composition:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type_metal

According to that page, the slugcasting alloy used in Linotype was 3% tin, 11% antimony, and 86% lead.

I’ve had the privilege of seeing a garage-kept Linotype in operation, and briefly operating it myself. “The mad machine that Mergenthaler made” has something like 3,000 moving parts; the sound is unforgettable.

Oh yes. And the pots were available with three methods…..

comes to mind:

http://rense.com/general72/TWILIGHT_ZONE_VOL32-13.jpg

(GOML) ;)

I was a little disappointed that they glossed over how the scanned image becomes a plastic plate. I’m curious what the technology was that accomplished that.

I suspect the method of turning the scanned image into a printing plate (which would have been state of the art at the time) would have been a proprietary secret back them.

Likely photolithography. The page would be printed onto a clear sheet, then etched onto the plastic sheet very much like printing a PCB board. I think this is much how it’s done today except that they skip the clear sheet and image directly to the plates.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_to_plate

I pretty much grew up in a hot-lead print shop. The most fascinating thing was to watch the Linotype machine operate. I had my first “aha” moment when I realized that the long array of oddly-shaped wheels on the left back corner controlled almost all of the actions of the machine. This set of cams and levers rotated under the command of the operator to control the most wonderful mechanical dance of arms, levers, shafts, and wheels. This opened the eyes of this young boy to the glories of technology – to my later great benefit.

And now the paper newspaper is in decline too as people move to the web and digital screens for reading, but there still remains in production the work of human hands and minds, well actually not even that given voice dictation and how mindless half the commentary in the new media is today, HAD excepted of course. :-)

My dad was a journalism professor back in the day and he used to have the university press print out a slug of type with the name of the top students in class and give it to them as an award.

When they shut down the machines he grabbed a drawer of the slugs, brought them home and had a friend make a coffee table from them – which I still have.

Rework one of them into a voxel-based dieselpunk 3d printer, with the casting system upgraded to accomadate a higher temperature, higher performance alloy such as Zamak?

After about two thirds of the movie they show what happens with these plates assembled from lines: unless I’m mistaken, they press a piece of cardboard with them, then the plates are done.

Surprise, surprise! One could certainly think of less complex ways to get a cardboard with all the pictures and types of a newspaper page punched in.

Do share your ideas-

I cannot think of a way more reliable, or editable up to the moment of final pressing than the operation they have set up.

Ideas? Well, two of them.

Instead of assembling casting matrices one could assemble positive characters directly, then put them into the plate. Needs a lot more prefabricated characters, of course, but they can be re-used. I think this is what was done before the Linotype, so I wonder a bit what the big advantage of this machine is.

Another one is to create not castings on the line assembly machine, but snippets of cardboard. Kind of a heavy impact typewriter, punching one line at a time. A snippet could make up several lines. Then these snippets get assembled to a page. Also editable, one can cut out and replace a line after assembly.

It’s a bit moot to develop such ideas in 2016, of course, the Linotype is gone for good anyways.

You realize that you need to make multiple plates to print the newspaper in parallel?

Making one negative and casting multiple positives out of that allows you to print much faster with more actual printers.

The Linotype is not gone for good. We are using a Linotype to set type for the purpose of printing poetry. I have been in the printing trade for over 70 years. Our poetry and some prose is set on a Linotype then printed on a handfed press. The press was built around 1910. There is Linotype slugs supplied to many of the greeting card companies and stationary printers. Sometimes we use a Hiedelberg windmill to print.

My high school, Lane Tech in Chicago, was teaching linotype in print shop along with computer typesetting. We made our own yearbooks, including making our own slugs. Went on til at least 1990, when I graduated. Good to move around and work with our hands instead of sitting down so much at a computer these days.

I used to work for a guy who had converted a Linotype to be a high speed bullet caster. He modified it to replace all the brass type molds with bullet molds.

Linotype is a great bullet casting alloy. What made it great for excellent detail on the type made beautiful looking bullets. Difficult to find Linotype alloy for casting anymore. Too bad.

All that lead and not a single pair of gloves. (c:

But Nanny, I can’t type with my gloves on. I can’t bend my fingers properly and they’re too big for the keyboard.

That’s quite enough of that young man!

Put your gloves on at once and don’t let me catch you without them again!

I swear I have this conversation at work once a month; can’t stand thick gloves.

https://www.amazon.com/Ansell-Edmont-11-501-10-Nitrile-Stretch/dp/B005QQC3T4/ These gloves are absolutely amazing. After a few hour’s adjustment I’m just as dextrous with them on as without. They don’t get hot or sweaty. They give really good feedback through the glove. They grip well. They don’t slide around. On top of that they’re cut proof. Won’t really help with lead, but for everything else. Last forever.

We just started using a similar type at my job but I may look at those ones. If they actually stay relatively dry they are a win. Difficult to find a pair that fit my strange fingers. Thanks! ;)

It was even worse back then. In the UK ‘Work Gloves’ bore an astonishing similarity to ‘Welder’s Gloves’ and were stiff as a board when new. It made holding small tools an absolute nightmare.

Saw this Vimeo at thisiscolossal.com — very cool site.

” Oh, and that title — ‘etaoin shrdlu‘ — is the linotype equivalent of ‘qwerty’. ”

I’m really surprised that at least three people didn’t jump on this and point out that “etaoinshrdlu” represents, in decreasing order of normal frequency of usage, the letters of the alphabet. The ‘qwerty’ keyboard was designed, by most historical accounts, to slow the typist down.

The “slow the typist down” is probably a myth. Probably.

The QWERTY keyboard is an effort at keeping the keys that were pressed most often in sequence, apart from each other. Because if you pressed two nearby keys too quick, the lever mechanism would get jammed. So QWERTY spreads them out.

Because to everyone here, who by the age of 8 did a frequency analysis of a Caesar ciphered text to determine the substitutions used, and decode it, it’s freaking obvious.

By the way, did you know that binary is based on the base 2 number system?

not a hack..

There’s probably a dozen hacks in those 3,000 mechanical parts.

T never get over the good feeling I have about my many years as a linotype operator. I was wise enough tyo learn this good skill before the war draft. I gave up a real nice income when I served four years in the military. Today many go in the military as a job and all the free government benefits AND peacetime service. My how things have changed.

I still use my Linotype Model 31 as part of my production of fine press books along with a large collection of foundry type. I also maintain a collection of 400 fonts for the machine. Everything here at Deep Wood Press is produced via letterpress or intaglio printing and is also hand bound into book forms.

While the computer can certainly do the job of typesetting, and in some cases a better job, the effect of type impressed onto quality paper in the form the person who designed the typeface intended cannot be improved upon for blackness of the page and many other aesthetic properties.