“Did you know you can 3D-print LEGO bricks that can actually be used as regular LEGO?”–me, in 2009

Those magical words made real to me the wonder that was 3D printing. It was a magical time! Everyone was 3D printing everything, though most of it wasn’t very good because the technology wasn’t there. But just as every technology goes through an evolution, the goalposts of coolness move on past what used to be remarkable to the new thing everyone’s talking about.

These days, no one is going to be more than mildly curious about your 3D-printed LEGO brick. Still, when you look at that uneven lump of plastic as being just one step in an evolution, it’s pretty momentous. What I’m saying is that we’re looking at a future that can be described in three words: Freakin’ Huge Bricks.

Re-Creating Those Basic Bricks

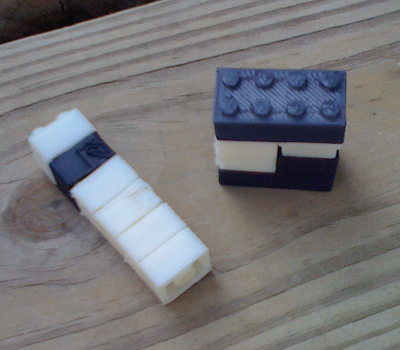

In 2009, LEGO started appearing on Thingiverse. wizard23’s Parametrized Lego Brick is a good example. The beginning definitely involved re-creating existing designs rather than coming up with new ones. No one was making crazy LEGO, because the crazy part was just the making of the brick. The output could be (and often was) the most iconic LEGO element ever, the 2×4 brick. They also tended to be badly printed as the community and the hardware toil to become ever better.

In 2009, LEGO started appearing on Thingiverse. wizard23’s Parametrized Lego Brick is a good example. The beginning definitely involved re-creating existing designs rather than coming up with new ones. No one was making crazy LEGO, because the crazy part was just the making of the brick. The output could be (and often was) the most iconic LEGO element ever, the 2×4 brick. They also tended to be badly printed as the community and the hardware toil to become ever better.

Interestingly, however, digital re-creations of LEGO bricks weren’t anything new even as much as a decade ago. Digitizing LEGO elements started way earlier. In 1995, back when most people’s idea of a 3D printer was “tea, Earl Grey, hot”, a young Australian LEGO nerd named James Jessiman released a DOS LEGO building program with a library of only three bricks: 2×2, 2×3, and 2×4. Tragically, Jessiman died from complications of the flu in 1997 at the age of only 26. However, his estate made LDraw a nonprofit organization in 2002 and it has taken the lead in digitizing every new LEGO release in a thoughtful, peer-reviewed manner. No element is added to the LDraw library unless a committee clears it. It was also made to be platform-neutral, so any independent LEGO building program could draw using LDraw’s designs.

LDraw’s unique CAD architecture was created before Open Source was an everyday concept, and consequently it followed some unusual precepts. Each element’s data file consists exclusively of text instructing some sort of engine to draw certain shapes. Smaller parts of a main design, like studs, are their own file. So, a normal 2×2 brick might actually consist of many sub-files. The basic shape is a rectangular box with a second box inside of it, inverted. Each of these is its own file referenced from within the main part file. The edges of the brick are geometric primitives drawn ad-hoc, but the studs are four instances of a separate file.

The LDraw project was important because for the first time, and thanks to the nascent Internet, überfans were taking control of the product. They had hundreds of legacy sets to digitize, and as each new set came out it was eagerly examined for new parts. The resulting library explores dead product lines and obscure one-off elements. It had been intended for use in virtual building programs, but it had an unintended benefit: yeah, we can print ’em. Just look for an import tool to drop your LDraw file onto Blender, for instance, and from there you can print anything.

The LDraw project was important because for the first time, and thanks to the nascent Internet, überfans were taking control of the product. They had hundreds of legacy sets to digitize, and as each new set came out it was eagerly examined for new parts. The resulting library explores dead product lines and obscure one-off elements. It had been intended for use in virtual building programs, but it had an unintended benefit: yeah, we can print ’em. Just look for an import tool to drop your LDraw file onto Blender, for instance, and from there you can print anything.

(I should point out that LEGO fans aren’t the only ones following this dream. O.G. LEGO hacker and LDraw ninja Philo T. Hurbain created a VEX library for LDraw that allows you to build virtual VEX models exactly the same way as one would with LEGO. Thingiverse has dozens of variants of the classic K’nex connector, as well as VEX-compatible parts galore. Finally, sometimes the building set manufacturers see digitization as a promise and not a threat: robotics building system Actobotics provides STEP files for every part, and these can be dropped into your favorite CAD program.)

Owning the Schema

The early focus in Thingiverse was the novelty factor of “gee, printing LEGO that actually could be attached to ones you bought in the store”. I have photos from the hackerspace of terrible LEGO prints from our Cupcake, but they were insanely cool at the time. Remember learning that you could dye them in RIT?

As designers grew more confident, they created more practical projects. For instance, a GoPro mount with LEGO Technic mounting holes. Adapters and connectors, that sort of thing. Art collective Fat Lab created the now-classic Free Universal Construction Kit in 2012 as a sendup of all those earnest adapters. With this kit, you could connect everything from LEGO to Tiddlywinks to Lincoln Logs.

This is another example of superfans taking ownership of LEGO’s schema as a building standard. Forget branding, here was a standard that could be applied universally. You can’t copyright brick shapes or Lincoln Log shapes or any other kind of building set — only trade dress. There’s a reason why LEGO has their name stamped on every stud. But if you can re-create that brick without the logo on it, it’s yours.

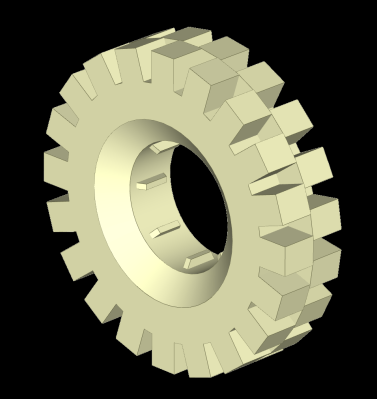

In another example of technology giving users control over the standard, parametric models have proliferated, allowing users to modify brick configurations to create elements that might not even exist. [cfinke]’s Customizable LEGO-Compatible Brick is as close to a single tool you might need to create any hypothetical element. You can create a brick, plate, or other shape with whatever combination of studs, cross-axle holes, and Technic mounts you want, regardless of whether this is something you’d see coming out of the company’s official offerings. You can also specify studs on the top, the bottom, both, or neither. You can make bricks so weird they’d be impossible to mold or print.

In another example of technology giving users control over the standard, parametric models have proliferated, allowing users to modify brick configurations to create elements that might not even exist. [cfinke]’s Customizable LEGO-Compatible Brick is as close to a single tool you might need to create any hypothetical element. You can create a brick, plate, or other shape with whatever combination of studs, cross-axle holes, and Technic mounts you want, regardless of whether this is something you’d see coming out of the company’s official offerings. You can also specify studs on the top, the bottom, both, or neither. You can make bricks so weird they’d be impossible to mold or print.

[Steve Medwin] is another fan who is exploring with parametric LEGO shapes. Some of them are playful: his Customizable Curved Beams as well as his Customizable LEGO Technic Hub allow you to make your own parts that the company never would, but which (ideally) connect to official parts. Creating an all-new element moves the dialog to go beyond copying some Danish engineer’s work and demonstrates that this standard can’t be contained or controlled — it’s out in the wild now.

The Next Evolution: Going Big

So, for years and years people have been digitizing bricks, but only recently has the print quality gotten to the point where LEGO parts can be printed with a quality even approximating that of the company’s ABS castings. Let’s face it, the LEGO Group has an iron-clad reputation for sterling engineering and quality control. It’s a big reason why nerds like it — not branding, not nostalgia, but simply the care put into the design and production of the physical part.

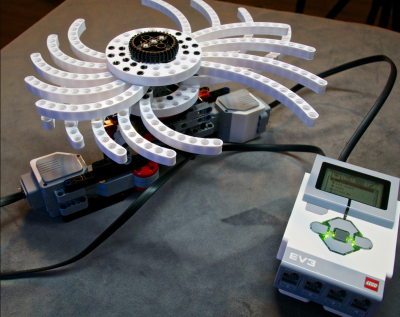

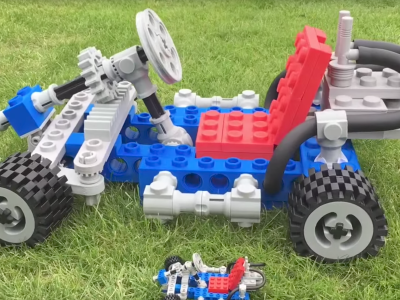

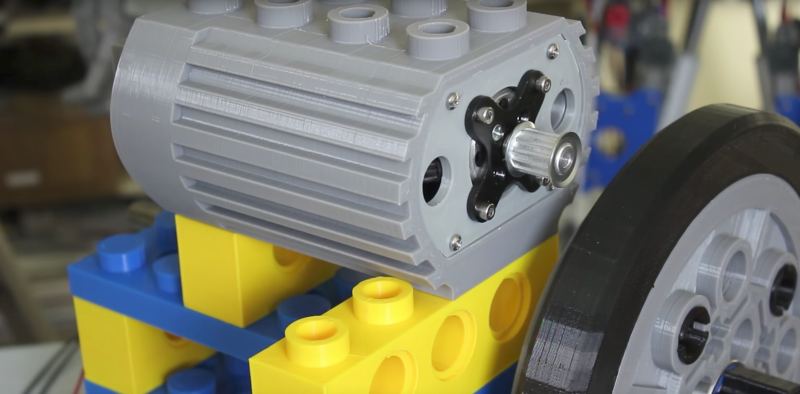

But in the past couple years, technology has started to catch up with the digitization. Only recently have we been able to use hobbyist-quality printers to output with enough precision to do justice to the official product. And you want to know another thing? People are printing BIG. Why make a tiny LEGO thing when you can make a big one? On Hackaday we recently wrote about James Bruton’s oversized LEGO skateboard. It consisted of giant bricks (pictured) that he glued together to make a badass electric skateboard. His friend Matt Denton took it a step further by building a quintuple-sized go-kart that is printed so precisely out of ABS that he was able to assemble and disassemble it without the need for glue and supports. The Ninjaflex tires fit over plastic rims just as easily as the normal-sized versions do. Bushings secure the ends of cross-axles as expected.

These giant models were made possible by improved 3D printers that not only offer vastly improved precision (allowing the larger parts to actually work as a functional building set), but also have larger build platforms, so the parts can be made big. The Taz5 printer employed by both [James] and [Matt] features an 11″x 11″ build platform and was rated the best overall printer in MAKE’s 2016 3D printer roundup.

However, as badass as these projects are, they merely scratch the surface of what’s possible. Both men made projects out of commonplace parts found on Thingiverse. [Matt] built a sized-up version of an existing model. When the Taz5’s quality becomes commonplace, expect to see a lot more parts in weirder configurations.

Also expect to see oversized building set parts — suitably customized through parametric models — becoming elements of high-quality furniture. Who wouldn’t want a set of ABS shelving reinforced with 80/20, or a table lamp that looks like it came out of a toy house but for its internal wiring. It’s all possible, and you have the tools to make it happen. Build something freakin’ huge.

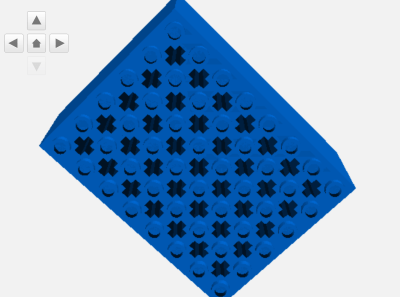

Tinkercad.com recently released a “Brick” feature. With a click of the mouse you can convert a 3D design into a bunch of Lego bricks. There is still some features to add such as a brick list but its cool just the same.

Wow, that is super cool!

Sorry, I just wanted to reply instead of report!!! Forgive it!!

(What I wanted to say is I wish Tinkercad.com -or any similar alternative- could be a self-hosted, free as in freedom service).

I’m hoping that at some point someone creates a modular system, based on fixed measurements that works on multiple materials is easy so one can do a DIY version (ex: in wood ) with just simple tools and gives you the same amount of pleasure as legos. my biggest problems with legos are price, availability and that everything you do looks so lego-ishhh :)

Making regular Lego brick with wood isn’t hard to do at all! Just cut some wood in the proper dimensions for a brick, drill holes in the top and bottom as deep as the stud height, then glue and/or screw in dowel sections that are twice stud height. Done. The trickiest part is the precision needed to make everything line up.

Yet another actual use for my 3D printer that’s been languishing after printing some Raspberry Pi cases

“So, for years and years people have been digitizing bricks, but only recently has the print quality gotten to the point where LEGO parts can be printed with a quality even approximating that of the company’s ABS castings. Let’s face it, the LEGO Group has an iron-clad reputation for sterling engineering and quality control. It’s a big reason why nerds like it — not branding, not nostalgia, but simply the care put into the design and production of the physical part.”

That really should be rendered in bold because not just LEGO will have to deal with any failures in the above (miniatures). LEGO is kind of the “Hello World” in the 3D printing domain because that’s probably what a lot do with their shiny new printer, till one realizes it’s cheaper and better to buy the real deal.

Printing a missing piece is cheaper than going around trying to buy one, because you always have to buy a kit and spend time and money for postage or travel.

Um no https://shop.lego.com/en-US/Pick-A-Brick-11998

Thankyou!

Or https://www.bricklink.com/catalog.asp for shopping from different second hand resellers (and find some parts and/or color Lego doesn’t provide anymore, like “OldGray” color).

Nice to see the parametric software starting to be made and released. A lot of designs are great when at LEGO scale but not so great structurally or mechanically when scaled to “full size” though.

Like making a full sized bridge or a house out of just LEGO. Not a great idea from an engineering perspective.

James May built a house out of LEGO.

He did. Well, sort of. The several hundred volunteers built most all of it, before it was torn down. But in the segment where he was talking to real structural engineers about it, they went over some of their concerns and some of the reasons why LEGO is not a suitable building material for a full sized house. Neat idea and neat video clip.

https://vimeo.com/120572139

“when you look at that uneven lump of plastic as being just one step in an evolution”

Yeah, I suppose we are constantly stepping on those Lego bricks of evolution.. and there are more and more of them.

Unfortunately, LEGO rely on the mechanical properties of the plastic to stick together, and those properties don’t scale up with the geometry, so the geometric stiffness of the blocks are different and they either won’t stay together, or develop cracks where the parts are compressed together.

I’ve seen concrete blocks that ‘click’ together like LEGO though, albeit relying on gravity instead of tension

That would be a completely different thing, since concrete has almost no strength in tension. They’re just stacked.

Maybe they have springy rebar?

Rarely. They’re made to cost.

I’ve 3D printed large Legos (7″) that lock together fine. They scaled up fine.

Not to mention how expensive they are.

I’m still most impressed by using legos to build most of an object, and 3d printing the remaining shape.

https://hackaday.com/2014/01/28/fabrickation-combining-lego-and-3d-printing/

Aren’t these bricks patented? Is it legal to do this?

… also, I would think injection molding would be a much better choice in this case as opposed to 3d printing.

The patent expired long ago. Hence the multitude of LEGO-compatible products being sold.

The patent expired in 2011: https://boingboing.net/2011/10/21/expired-patent-of-the-day-lego.html

How about a giant skeleton? I designed one at 10x scale https://www.myminifactory.com/object/42077

Just an idea here. Instead of building houses out of corrugated metal in some regions, couldn’t we build them out of giant lego like blocks? I am not saying there wouldn’t be challenges….but for temporary housing, or refugee camps….just an idea.

Probably cheaper and easier to just use some form of tenting? Rigid framework with some kind of fabric over.

That might depend on the environment, the weather conditions, and the duration.