There’s a fairly good chance you’ve never tried to embed electronics into a chunk of concrete. Truth be told, before this one arrived to us via the tip line, the thought had never even occurred to us. After all, the conditions electronic components would have to endure during the pouring and curing process sound like a perfect storm of terrible: wet, alkaline, and with a bunch of pulverized minerals thrown in for good measure.

But as it turns out, the biggest issue with embedding electronics into concrete is something that most people aren’t even aware of: concrete is conductive. Not very conductive, mind you, but enough to cause problems. This is exactly where [Adam Kumpf] of Makefast Workshop found himself while working on a concrete enclosure for a color-changing barometer called LightNudge.

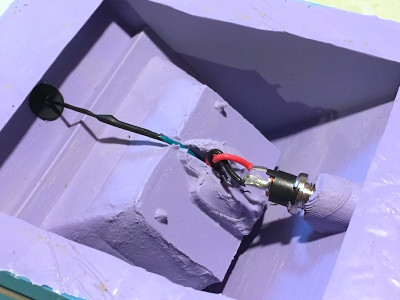

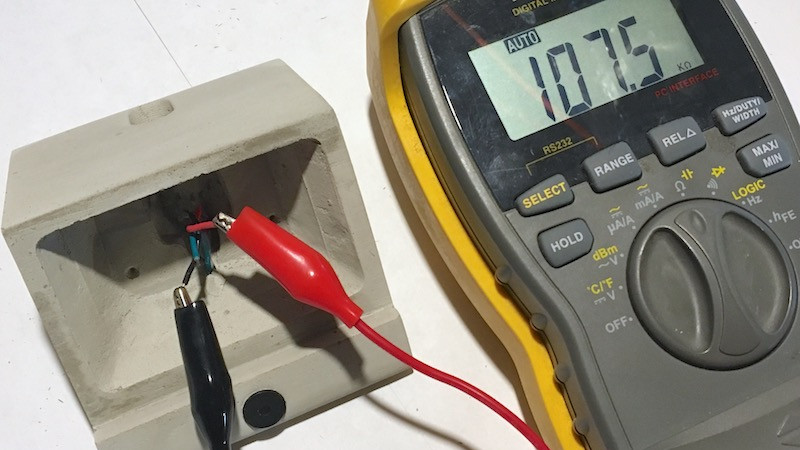

While putting a printed circuit board in the concrete was clearly not workable, [Adam] was hoping to simplify manufacturing of the device by embedding the DC power jack and capacitive touch sensor into the concrete itself. Unfortunately, [Adam] found that there was a resistance of about 200k Ohm between the touch sensor and the power jack; more than enough to mess with the sensitive measurements required for the touch sensor to function.

While putting a printed circuit board in the concrete was clearly not workable, [Adam] was hoping to simplify manufacturing of the device by embedding the DC power jack and capacitive touch sensor into the concrete itself. Unfortunately, [Adam] found that there was a resistance of about 200k Ohm between the touch sensor and the power jack; more than enough to mess with the sensitive measurements required for the touch sensor to function.

Even worse, the resistance of the concrete was found to change over time as the curing process continued, which can stretch out for weeks. With no reliable way to calibrate out the concrete’s internal conductivity, [Adam] needed a way to isolate his electronic components from the concrete itself.

Through trial and error, [Adam] eventually found a cheap method: dipping his sensor pad and wire into an acrylic enamel coating from the hardware store. It takes 24 hours to fully cure, and two coats to be sure no metal is exposed, but at least it’s an easy fix.

While the tip about concrete’s latent conductivity is interesting enough on its own, [Adam] also gives plenty of information about casting concrete parts which may be a useful bit of knowledge to store away for later. We have to admit, the final result is certainly much slicker than we would have expected.

This is the first one we’ve come across that’s embedded in concrete, but we’ve got no shortage of other capacitive touch projects if you’d like to get inspired.

I would expect moisture permeability of “regular” concrete (& plaster of paris)to cause problems with this use.

Is Hydraulic Cement any better of an option?

Or is it the actual composition of the concrete that is conductive?

Concrete is conductive in large part due to excess (free) water not used for hydration. IIRC, hydraulic cement will generally be conductive, though possibly less so than standard concrete.

The conductivity is often considered a feature, as concrete encasement is required for earth ground rods in many circumstances, and steel structures on concrete often have simplified earth grounding since the concrete, in particular bar or wire screen reinforced concrete, can do much of the job.

On the other side, this is one of the reasons for the special protections required for swimming pools and the like, though not the only one. (even if it was insulating, there could still be a fault to ground for other reasons, but the conductivity of concrete pretty much insures it from the start.)

Curing of concrete continues for decades.

Once cured Concrete also tends to take on the moisture content of the environment.

Very nasty environment for electronics.

It is possible to tie earth straps from a lighting rod to the concrete supports of a structure rather than a separate earth. This practice though is frowned apon in other circles as the current flowing through the concrete can superheat the moisture and causevit to blow the concrete apart!

“It is possible to tie earth straps from a lighting rod to the concrete supports of a structure ”

Only an insane person would do that.

Embedding an earth grounding conductor in the footing of a building is called a “concrete encased electrode” and is in the National Electrical Code as an effective alternative to an electrode (ground rod). In fact, it works well for lightning since the conductive concrete has a lot of surface area contact with soil. Using rebar to conduct a path to ground is not allowed unless the rebar path is electrically bonded, not just incidentally bonded by proximity or concrete. So that concrete encased electrode must have a continuous conductor path up out of the ground where it can be wired to the building main ground bar or electrical panel.

In Canada, I don’t see many poured concrete buildings with lightning protection systems (lightning rods) on the roof. They do get hit by lightning. But you would be challenged to find the attachment point. Seems lightning finds it’s own incidental dispersion through concrete and rebar without causing damage.

Your comment doesn’t change my view.

You view it however you wish…

The rest of us will stick with the relevant building regulations as the law requires us to.

..in our respective countries, assuming we don’t become victimized by mistakes from our respective governments.

P.S. Grenfell was up to code wasn’t it? Great; great.

Look up “Ufer Ground”.

Done all the time.

Originally for ordnance storage bunkers.

Yup, to my knowledge, most radio sites with a halo ground also tie it into a Ufer ground in the structure’s footing.

Maybe it helps to spray the whole circuit with a protective spray such as “Plastik 70” or “Urethan 71”.

Seems like a perfect job for conformal coating.

Concrete is also acidic as it cures.

This is also one of the reasons why cell phone and wifi signals does not play well with concrete buildings: it is conductive and lossy. Not a good dielectric at all. It even reflects better than it transmits RF signals. Another reason is the steel in reinforced concrete.

Hmm, I wonder how concrete changes based on enviornmental factors? Could one build thermometer or some kind of humidity sensor? Or construct RF circuits from different mixes of concrete and re-bar?

Could you make a touch sensor that detects when you touch the concrete?

And do NOT dismiss that concrete structures themselves display electrokinetic properties when stressed. This can be a useful thing but difficult to put in to practice in an absolute sense; easier in a differential sense.

Keep in-mind there are conductive effects within the concrete structure itself due to the likes of moisture and/or rebar, and then there are the effects of pre-stressing of the structure. Of-course all this changes over time as the concrete based structure ages.

Start by doing a Web search for the likes of:

piezoelectric effect concrete

electrokinetic effect concrete

Returns will likely be sparse (this is a specialized subject), and most papers will be behind greedy-corrupt paywalls (even though most papers are taxpayer funded). But by now, you should know how to work around this with reasonable results.

As for the work cited in this HaD post… When it comes to embedded vs. bolt-on – go for bolt-on (almost) every time. Embedded is a one-way-trip. Just my opinion.

Speaking of “embedding electronics in concrete” – Previously, on Hackaday:

https://hackaday.com/2016/12/03/thwomp-drops-brick-on-retro-gaming/

This fact is widely-known by all electricians. Concrete wall can be a handy Earth reference, especially when you are working on a ladder for a home improvement project. Turn on your DMM to measure voltage, plug one tip to the “hot’ wire of the mains, and another to the concrete wall, it’s likely that you would see the correct voltage.