We just wrapped up the Power Harvesting challenge in the Hackaday Prize, and with that comes some solutions to getting power in some very remote places. [Vijay]’s project is one of the best, because his project is getting power in Antarctica. This is a difficult environment: you don’t have the sun for a significant part of the year, it’s cold, and you need to actually get your equipment down to the continent. [Vijay]’s solution was to use one of Antarctica’s greatest resources — wind — in an ingenious flat pack wind turbine.

There are a few problems to harvesting wind power in a barren environment. The first idea was to take a standard, off-the-shelf motor and attach some blades, but [Vijay] found there was too much detent torque, and the motor would be too big anyway.

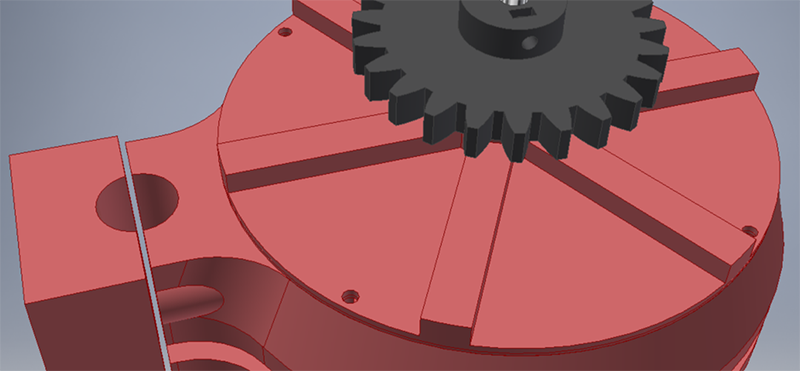

The solution to this problem was to wind his own motor that didn’t have the problems of off-the-shelf brushless motors. The design that [Vijay] settled on is a dual axial flux generator, or a motor with a fixed stator with magnets and two rotors loaded up with copper windings. Think of it as a flattened, inverted version of the motor on your drone.

One interesting aspect of this design is that it takes up significantly less space than a traditional motor, while still being able to output about 100 Watts with the wind blowing. Add in some gearing to get the speed of the rotor right, and you have a simple wind generator that can be set up in minutes and carried anywhere. It’s a great project, and we’re glad to see this make it into the finals of The Hackaday Prize.

Is there a chart of windspeed vs. power somewhere? I wasn’t able to easily find any results of the testing on the project page.

I don’t think the Hackaday prize requires test results at this time (maybe only for the final round?). Also due to logistics (place hard to got to) I think this guy may have done this project as a “quick side thing” while working on more important (funded) science down there.. so he may not really have usable results at all!

Helical vertical turbines get at best 35% efficiency.

Wind power = 0.5 * density * cross section * V^3

So just plug that in for your local weather conditions.

That’s the embedded power. The actual power you get out must be corrected with the turbine efficiency which maxes out at 59% in the ideal case. The turbine efficiency changes with the wind speed, with the general rule of thumb being, the more blades you have the earlier it saturates and drops off.

People think it’s better to have many blades, and then they calculate the power they would get at say 30 ft/s winds without considering that the turbine is acting like a barn door against the flow because it would have to spin ridiculously fast to pass the air through.

The picture gets slightly complicated because you have to calculate the tip speed ratio, which depends on the load you place on the turbine because a generator obviously slows it down.

The motor description above is entirely wrong. The motor has a fixed set of stator coils that are compressed like a pancake. On either side is a set of rotating magnets. It’s very much like the PCB motor, except with magnets on both sides.

“It’s like the motor on your drone”, except that the motors on my drones are either brushed DC or radial flux ICBMs. It’s like them in that it has coils of wire and moving magnets, I guess.

I’m submitting a flat pack solar panel :P

CityZen, is correct Benchoff’s write up doesn’t match what’s seen at hackaday.io. The Hugh Piggott alternator design used here, can’t be seen as revolutionary anymore, although construction techniques can be come evolutionary. This possibly evolutionary, but until details are easily visible I can’t get to excited over it. All see at the project page are photos. Given the operational speeds and load metal bearing are probably a given, so I’d be curious as to how they would be lubricated in the Antarctic environment.

Great way to burn a hole in one’s shirt… and what’s with the glove?

I designed an alternator a lot like this only I am not fond of winding coils (note that the 3D printer to flat coil winder project you published a while back might change that for me.. If I ever build one…) My deign was a wee bit different in that I used PCB’s with the coils etched on them sandwiched together. I think this has more loss but results in a much stronger part and is a lot easier to manufacture. Also, and I have not tried this, but I was pondering encapsulating the magnets in the 3D print. Encapsulating metal parts in a 3D print is one thing that I can not say that I have recalled seeing here that I have been wanting to play with.

Not much motivation to move on this….

… unless you have been there.

Ahem….