It is a good bet that if you look around you, you’ll be able to find at least one smoke detector in sight. If not, there’s probably one not too far away. Why not? Fires happen and you’d like to know about a fire even if you are sleeping or alert others if you are away. During the cold war, there were other things that people didn’t want to sleep through. [Msylvain59] tears down two examples: a Soviet GSP-11 nerve agent detector and a Polish RS-70 radiation alarm. You can see both videos, below.

In all fairness, the GSP-11 is clearly not meant for consumer use. It actually uses a test strip that changes colors and monitors the color change. Presumably, the people operating it were wearing breathing gear because the machine could take quite a while to provide a positive output. Inside reminded us of a film processing machine, which isn’t too far off.

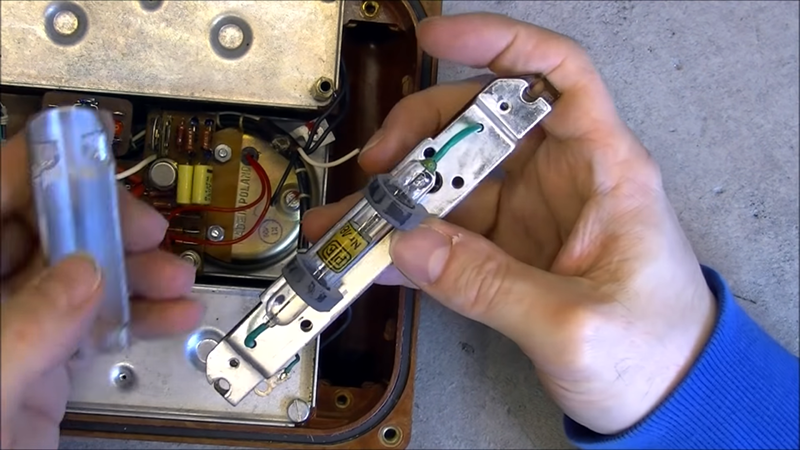

The radiation monitor looks more like a miniature version of an old floor-standing radio. The case design, the thick-traced, single-sided, hand-drawn printed wiring board, and the –by today’s standards — huge parts within all contribute to making this look like a piece of radio gear from the 1970s or even earlier.

If your Russian is any good, you might like the filmstrip about the GSP-11, although [Msylvain59] translates part of it for you. While the GSP-11 is like a little chemistry lab, the radiation alarm works just like you think it would: a Geiger tube (or a Geiger-Müller tube, if you want to be pedantic).

As you watch the videos, it is interesting to contemplate how different these would look today with solid-state sensors and microprocessors controlling everything. It is also sobering to remember the time when these seemed likely to be used for their intended purposes.

Lol, googled the device name for information, found out that I can buy one in place nearby for less than 100$.

If you want to check out a soviet dosimeter used in tanks and armored transporters, here are some photos of internals:

https://www.elektroda.pl/rtvforum/topic2727644.html

The funny part is, even so many years later, the common US military detector for nerve/blister/blood/choking agents is still a chemical reactive piece of treated paper tape.

I see that there were some digital detectors ordered in 2016, but I never heard anything about them while I was in the military.

It’s only recently starting to drive for major adoption, based on the news articles that I’m seeing now, bring up articles about the Joint Chemical Agent Detector (JCAD).

Why complicate things? If the paper strip does an effective job, sounds like the perfect solution. It would be cheap and easy to put into a chem warfare auto injector set, no batteries, and I would assume a pretty good shelf life when sealed up. The digital units are probably better for highly mobile units that need a real time alarm capability on the battlefield but not something that every person might have on them.

He means that the monitoring devices still use disposable paper on a reel, that needs to be changed regularly, stored properly, and has a shelf life. A digital upgrade would VASTLY reduce both the maintenance requirements, and the logistical support required to keep units in service.

But yes. For doing casual tests, paper wipes are used by hand in suspected areas of contamination. But there really isn’t a need to have a sample kit on every soldier. You either have a reason to expect contamination, and can call for a test, or you don’t.

Does it work with Novichok?

I have some geiger counters at home, old ones with high-voltage vibrators and “newer” units from late 20th century. They all rely on gas filled tubes and high voltages, so no fancy semiconductors as detector.

These semiconductors are available now, I even remember a trick using masking tape on your phone’s lens so it gets dark and you can see particles coming through as a white dot. Don’t know how that is going on nowadays. But there is some fancy stuff for sale but at high prices. The old ones work just as fine.

Relevant technology if you are an Israeli trying to survive while surrounded by enemies.