Digital electronics are all well and good, but it’s hard to ignore the organic, living qualities of the analog realm. It’s these circuits that Kelly Heaton spends her time with, building artistic creations that meld the fine arts with classic analog hardware to speak to the relationship between electronics and nature. During her talk at the 2019 Hackaday Superconference, Kelly shared the story of her journey toward what she calls Electronic Naturalism, and what the future might bring.

Kelly got her start like many in the maker scene. Hers was a journey that began by taking things apart, with the original Furby being a particular inspiration. After understanding the makeup of the device, she began to experiment, leading to the creation of the Reflection Loop sculpture in 2001, with the engineering assistance of Steven Grey. Featuring 400 reprogrammed Furbys, the device was just the beginning of Kelly’s artistic experimentation. With an interest in electronics that mimicked life, Kelly then moved on to the Tickle Me Elmo. Live Pelt (2003) put 64 of the shaking Muppets into a wearable coat, that no doubt became unnerving to wear for extended periods.

Analog electronics parallel living organisms while programmable logic merely simulates life.

—Forrest Mims

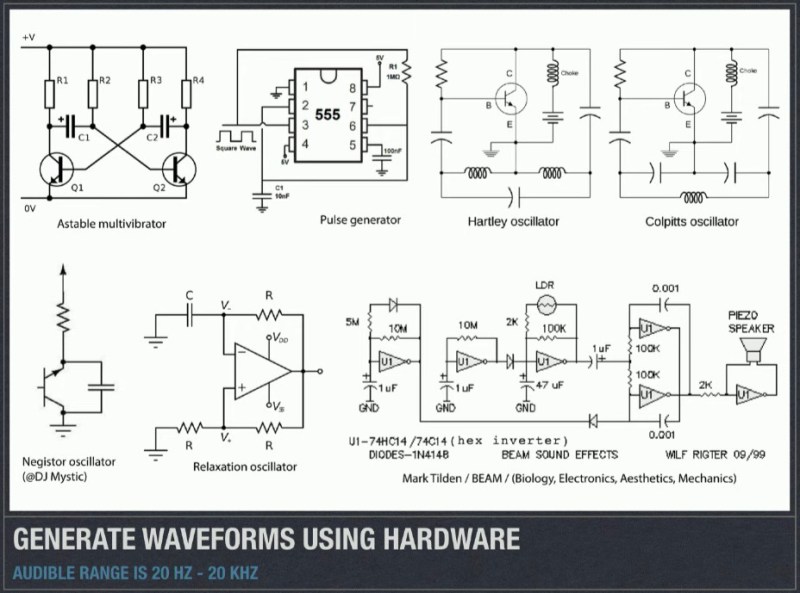

Wanting to create art with a strong relationship to organic processes, Kelly focused on working with discrete components and analog circuitry. Basic building blocks such as the astable multivibrator became key tools that were used in different combinations to produce the desired effects. Through chaining several oscillators together, along with analog sequencers, circuits could be created that mimicked the sound of crickets in a backyard, or a Carolina wren singing in a tree.

The work didn’t stop at a few sound effects, however. These circuits were woven into paintings, with individual components playing both a functional role and a visual role in the piece itself. What followed was a series of paintings featuring circuits to create the sounds of the animal depicted. Other projects were more sculptural, such as the transparent mylar constructions of Birds At My Feeder (2019), or the noisemaking worker bees of Pollination (2015). The electronics itself, from the oscillators to the analog sequencers used to drive them, becomes part of the artwork itself. Kelly refers to the hardware as beautiful, and it’s a feeling recognised by many who can recall their first time peering inside the mysterious innards of a disassembled radio or television set.

Coming from a fine arts background, rather than an electronic one, there was plenty of learning to be done along the way. Kelly spent plenty of time in the MIT Media Lab, picking up things at a fast pace as you’d expect at one of the world’s premier hacker universities. During the production of The Parallel Series (2012), Kelly realised she was struggling to keep track of how her experiments worked, leading to a note scrawled in the corner of one piece: “I need to document these circuits for my own sanity”. Any maker that’s come back to a mess of wires on a breadboard after a few weeks away can relate to this experience. Kelly’s process also developed over the years, becoming more analytical. The sounds of various creatures were analysed for pitch, timbre, and tempo, to help guide the work to recreate them in analog hardware.

Kelly’s work goes beyond simple analog oscillators. Through years of tinkering, she’s learned many tips and tricks to creating a pleasing and thought-provoking artwork. Repetitive sounds can be annoying, even if they are a decent facsimile of one of Mother Nature’s creations. To temper this, and add in a little realism, randomness is introduced into trigger circuits to make them sound more natural. Often achieved with something as simple as the base of a transistor left unconnected, when filtered, this can act as a great way to organically recreate the sound of a field of crickets chirping at each other in the night.

Much of the work is done on breadboards, making experimentation easy. As the components used are cheap and readily available, there’s little harm to be done, with the worst mistakes causing at maximum, a few dollars in damage. The stacking and reconfiguration of various analog oscillators in this work draws parallels to the world of modular synthesizers, a world we’re sure Kelly would also enjoy exploring.

Overall, it’s a great talk that covers the journey of creating artworks that blend the traditional and the electronic. Kelly’s art has been celebrated and displayed in a wide variety of locations, and it’s inspiring to get a look at the process behind the creations.

Super cool! I love how the animal sounds are broken down into their fundamental parts then reproduced in a fairly straightforward way… I went in expecting something far more complex. But even when a problem seemingly so large as animal noises being replicated we analog electronics is broken down to bite sized chunks it becomes manageable. Really cool. This is going to be a lot of fun to play with.

Awesome! Hundreds of disembodied furby faces is a sort of horror that I’ve never contemplated, so it must count as good art.

I wonder how much prior work there is in the whole, “nature noises from minimal components” area. These days I guess you’d just drive a DAC from a microcontroller, but you gotta wonder how much thought went into that sort of thing with old electronic toys. You know, the ones where it sounded like they used a cheese grater instead of a speaker.

Anyways, trying to recreate a specific birdsong or animal call from passives, transistors, and 555s would be a fun project. Busy, busy, busy…

“you may live to see man-made horrors beyond your comprehension.”

— Nikola Tesla, 1898

IMHO the artwork would be improved if this quote was engraved on a small brass plaque in the midst of the sea of Furby faces.

Some of what you might think of as electronic toys from the 60s, 70s and 80s were more electro-mechanical with a battery driven motor turning a small gramophone type disk, for one or one of a few recorded sounds, which could include spoken voice. Their immediate ancestor was driven by a string pull and spring recoil (Still around among the battery versions) and their original progenitor being Edisons Phonograph Doll, which used a wax cylinder.

They tended to sound like the popular experiment of a needle in a paper cone or cup demonstration of sound reproduction of an LP, because that’s about as sophisticated as the playback mechanism was.

The internet provides: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYLBjScgb7o

THE FURBY ORGAN, A MUSICAL INSTRUMENT MADE FROM FURBIES

She should try evolving circuits in a simulator then seeing if they can be implemented in real life. Feed recorded sounds into the training function.

interesting stuff but somebody please fix the audio track. To some that white noise blast is loosely equivalent to fingernail scratching on chalkboard and Speaker should be dominant. Furby pond uniquely disturbing. I’ll Look for vid on Elmo coat later. Im sure its also perfectly strange.