What’s your work area like? Perhaps you’re mostly a software person, used to the carpeted land of cubicles or shared workspaces, with their stand-up desks and subdued lighting. Or maybe you’ve got a lab bench somewhere, covered with tools and instruments. You might be more of a workshop person, in a cavernous bay filled with machine tools and racks of raw material. Wherever you work, chances are pretty good that someone is paying good money to keep a roof over your head, keeping the temperature relatively comfortable, and making sure you have access to the tools and materials you need to get the job done. It’s just good business sense.

Now, imagine you’ve lost all that. Your cushy workspace has been stripped away, and you’ve got to figure out how to get your job done despite having access to nothing but a few basic tools and supplies and your own wits. Can you do it? Most of us would answer “Yes,” but how many of us have ever tested ourselves like that? Someone who has tested her engineering chops under difficult conditions — and continues to do so regularly — is Laurel Cummings, who stopped by the 2019 Hackaday Superconference to tell us all about her field-expedient life with a talk aptly titled, “When It Rains, It Pours”.

Trip from Hell

Laurel shared quite a bit of her background in the talk, which really showed how the circumstances of her life prepared her for her current gig. Right after finishing her EE degree she decided to take a little break from the action by helping her dad move his boat down the east coast of the United States. The short, relaxing jaunt she expected evaporated soon after setting sail when the boat broke down in about as many ways as a boat can. She soon found herself hanging upside down in the engine compartment trying to solder the regulator from a truck alternator into place with a butane torch, sewing a torn sail back together in the dark, and being towed back into port by the Coast Guard.

After that experience, a nice, safe office job would seem to be the logical choice, but instead Laurel went to work for Building Momentum, a technology development and education outfit based in Virginia. The company’s major clients are active-duty military units and disaster-response NGOs, leading Laurel to places like Kuwait during historic floods, or to a Marine Corps base after Hurricane Florence drenched North Carolina in 2018.

Watney Your Troubles Away

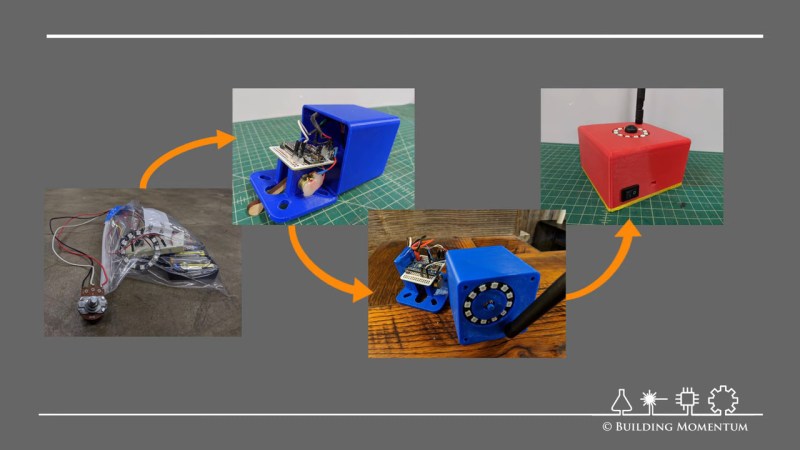

There she learned the importance of delivering something — anything — within 24 hours of arriving, which she stressed is important for establishing your bona fides as someone who can help rather than hinder. For the Marines, her team rapidly identified a problem — the base’s many emergency generators all had to be checked manually for fuel use — and built a version 0.1 solution, which ended up looking like a breadboard project in a plastic bag. But it was enough to get a toe in the door, giving her team the cachet needed to improve the design and pitch in elsewhere.

In her talk, Laurel outlined a simple but sensible process for attacking problems quickly. It’s designed for austere conditions, but it applies to everyday engineering just as well. Her approach to identifying the problems and deciding which ones to attack stuck out the most to me; to accomplish this, she suggests listing all the problems that the clients relate and then organizing them into a sort of “tag cloud” of similar issues. That helps find the real root issues and identifies which ones to attack first to deliver the most bang for the buck.

It sounds like Laurel has found a challenging and exciting work environment that’s a bit out of the ordinary. But when you think about it, a lot of engineers end up in similar situations. A lot of engineering gets done on remote mountaintops, at dams and in jungles, and in the bowels of ships far from shore. In those situations, one rapidly learns that if you didn’t bring it with you, it might as well not exist, and you have to make do with what you’ve got. Chance favors the prepared mind in those situations, and it sounds like Laurel has a leg up on her desk-bound colleagues in that regard.

[Main image via @BrucePerens]

Engineering and imagination go hand-in-hand.

1. Some people can do.

2. Some people can think.

3. Some people can imagine.

4. Some people can do all of these.

5. Some people can do none of these.

6. …and some people can build anything from two paperclips and and duct-tape.

Almost hacking your own foot off with an ax also counts?

Almost everything I do, I do while being in difficult situation. I don’t have a workbench for example. While working on electronics, I must be very careful, because my 3,5yo daughter will interfere. And I have only one, semi-working eye. All my tools are the cheapest money can buy. My scope doubles as exercise machine because it was made by Soviets and is built (abd weights almost as much as) T34 tank. Fully analog with big and long o-tube, but I converted it to DSO. The most expensive tool I have for electronics is genuine PICKit3 programmer. The most expensive tool I have is a 3020 CNC I’ve got for free from a very good man, who didn’t need it. I have 2 different end mills, few engraving bits and one drill for it. These things are a bit pricey, even if I buy cheapest ones on the market…

Soo you went on a typical fishing trip and did a talk on it?

Glad all made it home safe but cmon.thereifixedit has some more compelling fixes.

Great to put maker talents to good use for the benefit of people in need. I hope reaching out to the community of makers and hackers gets results. I’d be interested.

What’s my workplace like?

Generally I enjoy the job.. but there are moments when I start to wonder:

Last week I watched a co-worker attempt to drill a hole in a piece of aluminum channel with an impact drill and masonry bit..

if that is all you have it beats doing it by hand

But that’s what I don’t get.. we DO have more. All the right tools actually.. and a we share the building with another company with a full manufacturing center. So yeah..

Ah… friction drilling?

The best kind of drilling! For all your long-life drill bit needs! (extreme sarcasm)

You can do friction drilling with any bit, by reversing the rotation of the drill chuck!

Or observing someone destroy (burn up) a corded drill by drilling a 3/8″ (8mm) hole in a piece of 1/4″ (6mm) steel because they have the drill in reverse. We were busy and not watching too closely…we wondered why it was taking him so long….

“you’ve got to figure out how to get your job done despite having access to nothing but a few basic tools and supplies”

So, my life growing up on a (not very affluent) farm….

I enjoyed the talk. It’s always nice to hear stories about making the most of limited resources, or thinking outside the box.

That’s one of the biggest things I wish we could somehow teach better – basic problem solving. Having taught a university level class, it’s amazing how many of the TAs (who were Masters students) were incapable of figuring out some seemingly simple problems. It’s fine to say “I don’t know”, but it’s not fine to forget the rest of that sentence ” – but I can try to figure it out.”

Very neat talk, reminds me of my time in Haiti. I have very very little medical training, so most of my multiple years there I was fixing things, since, in Haiti “everything breaks, all the time”.

I would like to do more of that (meaning fixng under time pressure with little to no resources), but with my family and other commitments, I’m averse to travelling due to the tie away from them.

In Haiti I once did an alignment on a vehicle with a tape measure and some trash from the parking lot that I re-purposed. When it was challenging, it was very challenging (but sometimes fun). When it was difficult, it was very difficult.

I don’t regret spending those years of my life there and may do it again if the opportunity arises.