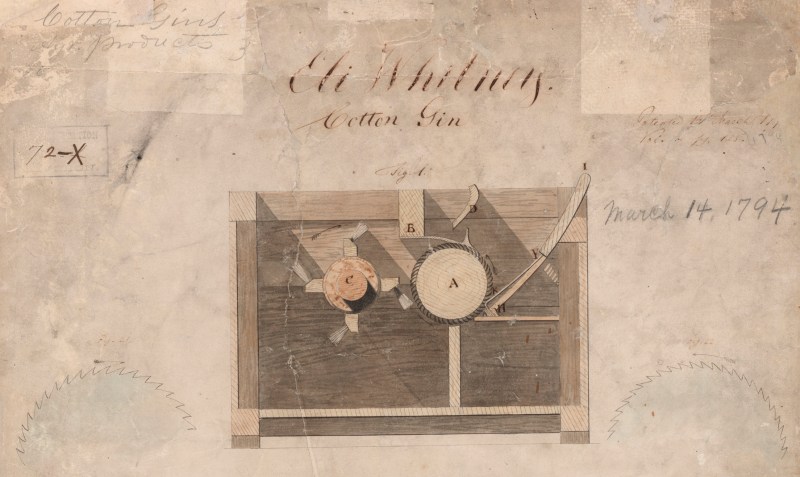

If you went to elementary school in the United States, you no doubt learned about Eli Whitney’s cotton gin as an example of how the industrial revolution took previously manual processes and replaced the low-efficiency of human labor with machines. The development of the cotton gin — patented in 1794 — involves an interesting lesson about solving engineering problems.

Farmers in the southern United States had a big problem. Tobacco was a cash crop, but it eventually left your fields barren and how to solve that problem wasn’t understood yet. Indigo was valuable for dye, but the British were eating away that market with indigo created in its colonies. Rice requires a lot of water and swamp, so it was only suitable for certain areas.

There was one thing that grew very readily in much of the land: cotton. Unfortunately, the cotton had little seeds you had to remove. A single person could clean — maybe — a pound of cotton a day. In the late 1700s, plantation owner Catharine Littlefield Greene introduced Whitney to a group of farmers were trying to decide if there was a way to make cotton a more profitable crop.

Solving the Wrong Problem

Reportedly, Whitney found inspiration in a very strange way. He couldn’t figure out how to remove the little entrenched seeds from the cotton. But one day he saw a cat trying to pull a chicken through a fence. The cat was unsuccessful but managed to get some feathers. That was the key: Don’t try to remove the seeds from the cotton, but remove the cotton from the seeds.

The gin — short for engine — had tiny hooks that would pull cotton fibers or lint through a mesh. The seeds couldn’t make it through. By changing the machine from one that removes seeds to one that removes cotton, the design was very simple.

An 1883 article in the North American Review claimed that Mrs. Greene had made some suggestions about the design of the machine. However, the author didn’t provide any source for the claim and it remains unproven. It wouldn’t be surprising, though. Greene certainly provided financial support as well as encouragement.

Greene’s plantation manager, Phineas Miller, became Whitney’s business partner. Whitney, Miller, and Greene did not intend to sell the gin, instead planning a model where they would own all the machines and take a percentage of the clean cotton as a fee. Cotton as a service, if you will. The gin could do about 55 pounds a day, so one simple machine and one or two people could do the work of at least 55 people.

Aftermath

The gin made cotton profitable which was a boon to the south, but did manage to keep slavery going for another seven decades — that wasn’t Witney’s intent, of course. The service model failed because the device was simple enough, that people copied it — illegally, in light of the new patent laws. In the end, he didn’t make the money he hoped for, although he did make some and became famous for his labor-saving invention. He would go on to pioneer the use of interchangeable parts in manufacturing, but that’s an entirely different story.

How many times are we faced with a problem that we can’t quite solve? It is worth taking a page from Whitney’s book and asking yourself how to flip the problem around to see if that helps. We are just glad the gin shorthand didn’t catch on as we’d hate to have to say we work as gingineers.

[Patent drawing via the National Archives]

I heard in school that the ‘gin’ was from genie or djin/dgin.

More likely it came from a shortening of ‘engine’ as that usage was recorded elsewhere: it seems to be a spontaneous contraction for English speakers.

Try the opposite way is one of the inventive principles of TRIZ. worth to mention that TRIZ itself was created by analizyng thousands of patents to confirm the initial hypothesis that several distinct problems might be modeled to a generic problem and then you iterate through the known generic solutions to such generic problem to figure out an specific solution.

It is a simple, but effective methodology to solve hard problems.

TRIZ is amazing and I don’t know why it isn’t more well known. Most of the 40 even have parallels in software.

so the cotton gin was in fact invented by a cat. curse you propaganda mill posing as elementary school!

Yet after all these years of cats showing us how we still haven’t figured out how to lick our own balls! (Now THAT would be a history changing development!)

Actually marilyn manson got a rib removed to facilitate autofellatio. I assume that means he could do as you suggest too.

Autofellatio? Isn’t that against the Highway Traffic Act?

A commonly-repeated but completely false myth

In actual fact, Marilyn Manson got a rib removed to make a woman. Absolute truth, I wouldn’t lie.

And it took valuable manual labor jobs away from African Americans causing disenfranchisement.

IIRC, a patent prevents someone from selling copies of an invention. It does not prevent someone from creating their own copy of the invention. It would not prevent someone from making a cotton gin of their own and then use that to process cotton.

Correct?

IANAL, so I could be entirely wrong, but a patent only allows non-commercial duplication/use. So even if you made your own copy of a patented gizmo to use in your business, that would still be infringement.

The patent “bargain” is that in return for a monopoly for a limited time, you have to publicly document the invention. The world gets to benefit from your genius, and in return you get to cash in for a while.

That’s the principle, anyway.

Sure but documenting the invention is to prove exactly what you did and didn’t invent. The public access is so your rivals know what they’re not allowed to use in their own inventions. Yes it’s a dead giveaway but back in the days of mechanical inventions, you’d mostly just need to take something apart to make it’s principles obvious, and even if they weren’t, a simple monkey-see copy would often work.

So the publication of the principles isn’t so much a complementary half of a bargain, as a necessary part of the protection. You have to specify WHAT you’re protecting, which is why there’s so much legal expertise and tightrope walking goes into making a patent as broad as you can get away with, but not too broad to be valid.

>Correct?

Incorrect!

No, not correct. You can’t just copy someone else’s design, even if you just intend to copy a design for your own personal use. Otherwise we’d have no need for a patent office. A U.S. patent is good for 14 years (I think it’s seven, but renewable for another seven.)

That said, people often work out ways to get around the patent. In one famous case, an inventor used a cam to convert rotary motion to linear motion. Someone else used an eccentric (like the big end of an auto connecting rod) to do the same thing.

Which is why we _DO_ need a patent office, and also lots of lawyers who represent both inventors and copiers.

Yes you can. The whole point of patents is that someone else can re-create the invention to investigate and evaluate how it works, and learn from it – just not use it or sell it for profit without a license from the original inventor.

The question is moot, because patent infringement is not a crime – it’s a civil liability so you actually have to be sued for it – and if nobody knows or cares that you’re doing it then you can just keep on doing it.

Whitney also introduced interchangeable parts for a military rifle contract -prior to this, parts were individually fitted for each firearm.

Not correct in the USA, but in some other jurisdictions, true.

In the US, even if for personal use, it is a violation to use a patented “invention” (the quotes because the rules use the word, but the definition has been stretched well beyond what common sense might imply). I do not know if the law was the same circa 1800, as any patents from that time are long, long expired, and there have been a lot of changes to the law since then.

The international laws, ad assorted interlocking treaties, make it a much more interesting problem, should your interests turn that way. My interests don’t, but I have an attorney who does have that kink.

Yes this appears to be a Euro vs. US thing. In Europe, you can make use of an invention privately, but you cannot sell instances of the invention. Presumably, this could extent to not being able to sell the cotton processed, but that is less clear.

It is the same in the US. You can copy any patent you want for personal (non-profit) use. You cannot sell another persons design or make a profit indirectly from it (as in the cotton gin example above).

IANAL, but I am a law student. I am going to try and condense down my very limited knowledge and hopefully convey an intensely complicated subject. I may not succeed.

A patent grants you, the patent holder, the right to exclude another party from exploiting the subject of the patent. Be it by copying, selling, or importation. But, It isn’t an automatic prohibition per-say, people could copy your invention and even sell it and nothing would happen at all (automatically that is). Conversely, you can permit another party to use part of all of your idea/invention.

Basically, what I am trying to get at is that the patent holder has the right to permit or exclude the use of their patented idea. But, nothing is “automatic.” The patent holder has to know about the infringement and has to actively exercise their right via legal action.

Good thing you aren’t asking about copyrights. Dear lord is that the king of subjectivity.

Future copyright laws may as well be written personally by Mickey Mouse, he’s basically responsible for the last several decades’ worth.

Even though he himself is a ripoff of some cartoon rabbit with the ears changed. The sort of irony and hypocrisy that is the DNA of corporatism.

“But, It isn’t an automatic prohibition per-say…”

Ummm, law student… get used to saying per se. Should save you mark downs on any student papers you submit. ‘-)

“Reportedly, Whitney found inspiration in a very strange way. He couldn’t figure out how to remove the little entrenched seeds from the cotton. But one day he saw a cat trying to pull a chicken through a fence. ”

And this is why cats rule. Hang around long enough and they’ll show us how to crack the sound barrier.

Have you never seen a cat make a quick getaway from its’ litterbox?

My cat does several subsonic laps around the house after taking a dump. And judging where he is running from, I can tell if he’s used the litter box, or the palm tree in the corner of the dining room…

It’s that brain parasite thing they get. How otherwise could such despicable and solipsistic creatures inspire such gurgling one-sided love and devotion?

You must be disgusting yourself, if you can’t appreciate the loveliness of cats. Of course they also produce excrement – like each of us. But that’s not important.

For the record, possums will also try to pull chickens through chicken wire. Also, they succeed where cats fail–my fail of the week, wrong mesh for bottom of chicken tractor….

Regardless of the intent of patent law, a patent is only a “hunting license,” and lawsuits are expensive, so going after individuals is not particularly practical. And back then waiting 17 years for the patent to expire was not an eternity.

When I toured the Museum of Science and Technology (that might not be its “real” name) in Birmingham, England, several years ago. I was surprised to hear the tour guide say the cotton gin was invented in England.

At one point Birmingham produced 80% of the world’s textiles, so they had a large area of the museum dedicated to that part of their history, The tours walked people around a large pit, In it was the equipment used to gin, card, spin, weave the cotton, the guides operated some of the machinery. After the tour, some of us stayed to watch the Jacquard Loom in action.

Definitely a “must see” place for any nerd to spend an afternoon!

Dang it!

I meant “Manchester”

(forgive me Utd and City fans!)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science_and_Industry_Museum

Yes. Highly recommended. It also has a working replica of the first electronic-stored-program-computer:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchester_Baby

Thank you for sending me down a 2 hour wiki hole!

Good place! When I went, years ago, they had a good dozen or so gigantic mill steam engines, all working, fed from a boiler off away somewhere. They weren’t powering actual factories so presumably didn’t need a lot of steam or fuel to operate, but still spun and chugged in their beautiful shiny glory. Genuine centuries-old stuff, given a bit of polish and working better than new. Try saying the same in a century, or 20 years, about anything made now!

Full of interesting information and the love the curators have for the place is obvious everywhere. There was a full-size rope race, huge big pulley with like 100 tracks on it, maybe 3 metres across. The place could have manufactured everything Victorian Britain needed!

It’s right near one of the big train stations too I think, Victoria maybe. Not much walking, through a lovely airy area with lots of water and trees.

It probably was. The machine used for long cotton. The American South was growing short cotton with fibers too short for the long cotton machines. The long cotton machines were ancient in India.