Who among us hasn’t dreamed of having some brainstorm idea, prototyping it, and then have some huge company put it into worldwide production? The problem is, that’s not really as easy as it sounds in most cases. Take the case of Robert Kearns. Never heard of him? You use the result of one of his patents pretty often; Kearns invented the intermittent windshield wiper.

If he had sold the patent to one of the big carmakers, this would be a short article. Not that he didn’t try. But it didn’t go very well and while, in the end, he prevailed, it was a very expensive victory.

“Neat, You Should Patent That!”

Early windshield wipers came with two settings: on and off. If it wasn’t raining very hard you had to turn the wipers on, then off, then on again a few seconds later. One of those minor annoyances, but an annoyance, nonetheless.

Early windshield wipers came with two settings: on and off. If it wasn’t raining very hard you had to turn the wipers on, then off, then on again a few seconds later. One of those minor annoyances, but an annoyance, nonetheless.

If you’ve driven a car made in this century, you know how an intermittent wiper works. You flip the switch and the wiper blade makes a pass. Then it waits a long time — usually a selectable long time — before it sweeps again. Just the ticket when you have a little sprinkling going on. Is this a solid enough invention to file a patent?

Patent law is a strange thing. An invention has to be non-obvious. You could argue that a wiper that pauses a bit ought to be pretty obvious, but there are several patents for just that thing. In 1923, Raymond Anderson patented an electro-mechanical design. He also mentions that others have made intermittent wipers using solenoids, but they were noisy. So the idea had to predate this 1923 filing. Like many things, it wasn’t a very practical idea until transistors came along. A British car maker’s engineer, J. C. Amos patented a solid-state intermittent wiper control circuit in 1961.

In 1964, three years later, Kearns patented his design. We aren’t patent lawyers, but it seems like people had thought of the idea and that using a transistor and an RC network to accomplish the goal probably was not novel. However, regardless of what you think of the grounds, Kearns got his patent. So we are halfway to our inventor-makes-good Cinderella story, right?

Windshield Wipers Inspired By the Eyelid

Kearns said that he had thought about the wiper because of an event that happened a decade prior while on his honeymoon. A champagne cork hit his left eye leaving him legally blind on that side. While driving through light rain, he found the wiper blade was distracting his already impaired vision. He thought about how the human eyelid didn’t blink on a fixed cycle and decided to try making a prototype.

He built a lab in his basement and used a windshield from the junkyard to do tests. In 1963, he had a prototype attached to a Ford Galaxie convertible. He drove that car to a meeting with executives at Ford.

He built a lab in his basement and used a windshield from the junkyard to do tests. In 1963, he had a prototype attached to a Ford Galaxie convertible. He drove that car to a meeting with executives at Ford.

Ford seemed interested but made no promises. They did ask him back for a second meeting, though. That meeting was with engineers who asked a lot of questions. They were apparently working on their own system for the upcoming Mercury. They continued to meet for two years, but Ford never offered him a business deal. By 1965, Ford stopped calling. I’m sure you can see where this is going. In 1969, Ford started offering electronic intermittent wipers.

In 1976, Kearns’ son Dennis took apart a wiper control box from a Mercedes-Benz. The circuit inside was an exact copy of the circuit in his Father’s patent. Kearns started looking at patent filings by Ford, General Motors, Volkswagon, and others. They had all just copied key elements of his design.

Legal Battles

Kearns filed lawsuits in 1977 against several car makers. While he had some legal help, he mostly acted as his own attorney. That cost him as apparently several cases were dismissed on technicalities an experienced attorney would have handled (for example, missing a deadline to file). It took 13 years, but Ford finally settled for $10.2 million. In 1992, Chrysler lost to the tune of $30 million, but an appeal and an attempt to go to the Supreme Court meant he didn’t really see that money until much later.

The cost was high. Kearns spent a lot of money pursuing these cases. He suffered a nervous breakdown and his long-standing marriage dissolved. While $10 million sounds like a lot — and that value in 1990 is closer to $20 million when adjusted for inflation — the real damages could have been much worse. In 1990, Ford had made 16.8 million cars with the wipers subject to the lawsuit. Kearns had been seeking $50 per infringement which would have over $800 million.

The carmakers did wait Kearns out in one way. By the time the cases settled, the patent had expired, meaning he only received damages during the term of the patent.

Pyrrhic Victory?

There’s a lot to think about here. While a patent is a great thing, it only helped Kearns because he was ready to go on a decade-long fight with companies that had much deeper pockets than he did. We aren’t sure the original patent was very novel and non-obvious, but the courts held them up, so that’s what counts.

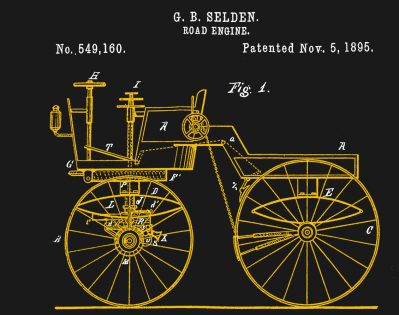

This doesn’t appear to be an isolated incident either. An earlier case mentioned in this 1983 Washington Post article showed that Ford infringed on a power steering pump patent and had to pay a ten-cent royalty on 6.5 million pumps. There have been recent lawsuits over hybrid systems (settled), turn signals, and MIT-developed emissions systems (which they won). Ford’s been embroiled in lawsuits over patents from the very beginning. In 1903, George Selden sued Ford and four other automakers over his 1895 patent for the Selden Road Engine. Selden won but then lost on appeal.

This doesn’t appear to be an isolated incident either. An earlier case mentioned in this 1983 Washington Post article showed that Ford infringed on a power steering pump patent and had to pay a ten-cent royalty on 6.5 million pumps. There have been recent lawsuits over hybrid systems (settled), turn signals, and MIT-developed emissions systems (which they won). Ford’s been embroiled in lawsuits over patents from the very beginning. In 1903, George Selden sued Ford and four other automakers over his 1895 patent for the Selden Road Engine. Selden won but then lost on appeal.

The topic of patents is certainly a messy one. Many think of them as a protection for the inventor’s breakthrough. But then you see that Ford sometimes patents the shape of windshields — possibly to prevent third-parties from making replacements. It isn’t just Ford, of course. Patents have become a dog-eat-dog business tool. Right or wrong, you better have deep pockets to defend your patent.

Kearns, who died in 2005, was the subject of the 2008 film Flash of Genius where Greg Kinnear played the inventor. During his life, he’d filed quite a few lawsuits in his quest to protect his patent.

My grandfather invented a very simple automatic windshield wiper system that adjusts the speed depending on the level of precip. We helped him patent it, but were never able to do much with it. Anyway, that was 20 years ago, the patent is expired and you can now build this yourself for your car. Never adjust your windshield wipers again, because the sensor will do the work for you. Check it out here: https://patents.google.com/patent/US5949150A/en

That’s pretty cool!

Patent law makes a tiny bit more sense when you consider that patents aren’t for ideas, patents are for implementations. An intermittent windshield wiper may be obvious, but how exactly to build one is not obvious.

Well… it is a hard line to draw sometimes, though. For example, I think if you told anyone you wanted a intermittent windshield in those days they’d think of an RC circuit. Even today, you might think that to reduce BOM and cost although a little 8 bit MCU is sure cheap now. So you might argue the idea is nonobvious, but the implementation was pretty straightforward. And the idea wasn’t novel to this patent because other people had prior patents.

I had an employer who shall remain nameless. We used to patent common computer circuits all the time because we might have been the first ones to build them on silicon. I always likened that to someone patenting the first radio built on a PCB even though they didn’t own the radio patent or the PCB patent. But we had a lot of money and we got lots of patents.

It’s not. A patent application requires you to specify some implementation. No matter how non-obvious the idea is, the implementation must be there in the application, and the description of the implementation defines the scope of the patent.

An idea like “A flying car” is not patentable. You must say how it flies, and the how it flies becomes the patent.

I believe many modern cars have automatic wiper systems based on optically registering the rain through the windscreen. Your grandfather’s patent may have been too specific in that it seems to be implying an electrical moisture sensor mounted on the exterior of the vehicle. It’s otherwise very similar to other systems that have been used for at least a decade in quite modest cars.

Mine does this but I am not sure how it knows. I know sometimes it false positives on a clear day. I have also seen systems proposed that measure the torque on the wiper motors. If they are working hard it rests them on the theory that it is less work to swipe a wet windshield. Not sure if these were ever produced or not.

Wind makes a huge difference in torque though.

I often manually operate mine intermittently. I’m paying attention through the windshield the whole time anyway, so I’ve invested nothing in noticing when visibility would be improved by another swipe of the wiper.

When you said “manually” for some reason I pictured how they were in the 20’s. They actually moved a lever that drove the wiper blades. It’s funny how the meaning of many words changes in a certain context.

While it’s still an optical system, the 2019 Ford Edge uses an infrared emitter and receiver and looks for increased IR return caused by the backscatter of the beam from the rain drops. I don’t know if it’s a sensor issue or a control software issue, but sometimes it gets really stupid and runs the wipers on high speed during a mist or will park them prematurely and then immediately do a wipe cycle. It’s not so annoying as to be unusable, but it sure could be better.

I got this system on my 2004 SAAB 9-3 aero. It works around 60% of the time, but needs to be turned off, and then on again from time to time. Otherwise it can start to act just as you describe. In some weather conditions it doesn’t work at all, and I’m back at manually turning the wipers on and off at suitable intervals :)

I purchased an eSID for my SAAB so I can toggle the mist wipe, wait however long I need then toggle it again. Then the eSID will maintain that intermittent interval.

We could always build it for ourselves, a patent prevents us from attempting to sell it to others.

This is region-specific, I found out when reading up on patent law around the world after that medical instrumentation company was threatening to sue Italian hospitals for printing their own flowmeters for their ventilators last month. There are countries in which patent law provides patent holders with the power to prevent any use of the patent, even for personal, non-commercial use, and even prevent ownership of a not-being-used copy of an item that’s been patented.

Not necessarily true, a patent gives the owner the right to prevent or stop ANYONE from making, USING or selling the claimed invention. So, in theory, an individual who is using a patented invention can be sued for patent infringement. But in reality, this is cost prohibitive and a patent owner would likely not file such a lawsuit.

I seem to remember that he actually didn’t get all that much of the settlement money. Apparently, to raise the cash needed for his legal fees, he sold off big parts of any settlement to investors. These investors put up cash for a percentage of any settlement, and they wound up with almost all of it.

The guy clearly was no economic genius.

I notice you haven’t made a better suggestion. At least he didn’t end up in debt.

I dunno exactly how I feel about this story. On the surface it sounds like a straightforward underdog getting ripped off by corporate bastards story, but how else were Ford etc supposed to have implemented their circuit? An RC delay circuit is the obvious, simplest, cheapest way of doing it. You’d have to deliberately add complications not to copy it. And what would they even be? Nowadays you might do it with a computer, and THAT uses an RC for it’s clock!

The original patent was a fluke, I’m surprised he won. I wonder if Ford etc went with “obvious, non-novel” as their defence? In good faith it’s what I’d have done.

That non-novel thing must be a bastard to prove though. I bet over half would get guessed after having problem described, by fresh 1st year September intake of Engineering students in a 1 hour beer and BS session. The next 30% by newly graduated haven’t actually been in the field B. Eng.s …. 15% of the rest by general “been around a bit” Engineers, and actual specialists in the field of the invention, they’d get the last 4.5% all in 1 hour of beer and BS… yup I’m saying less than half a percent is actually non-obvious.

The test for obviousness is that you imagine a person knowledgeable in the field but with no creativity. Would that imaginary person think of it?

That’s not the same as actual engineers who, be definition are ingenious and creative.

The patent system has all but killed the home inventor. They are expensive to get and expensive to defend, its essentially not worth it unless you command an army of lawyers.

I think it is even worse now that the US had joined the rest of the world in first to file. Big company can file many patents in the time it takes a small business to file one. And if you aren’t first to file, go home.

This is what happens when the first thing you don’t do is kill all the lawyers.

Before there were lawyers, Lord Soandso would simply inform you that you stole his invention and he’s hanging you and taking your estate, unless you want to face his champion in single combat. But if you do that and lose, then your family assumes your debts. (eg, they die) So you just let them hang you. It is kinda like bankruptcy, but without lawyers.

Yes, it’s never good to go from one extreme to the other. :-)

But the patent system really has some quite weird aspects to it.

There was neither any formal proof that the market is failing. The justification for the patent system is just based on lies and beliefs, as such it can be requalified as a religion.

The justification to a patent system is that industrial espionage happens, and people will copy your work without spending the money on R&D, so they’re able to undercut you on the market as soon as you are finished developing.

This happened in the Soviet bloc a lot. DDR used to copy everything from IBM mainframes to the actual Intel CPUs inside them and the manufacturing technology used to make them as soon as the chips were out on the market – because they simply didn’t give a toss about patents. There’s a similar deal about China. An guy I know works in the heavy industries, said to me that whenever they sell any machinery to China, they buy exactly one. A year later ten copycat companies show up. One time they showed up at an expo where there were already three different booths for their product.

I guess the point is that IP law isn’t applicable to hot or cold war opponents. America wasn’t going to restrict itself to asking politely for German submachine guns and Soviet satellites just because they invented them. It would be bizarre if the Soviets decided not to copy enemy CPU technology.

Copycats have their place domestically too, making technology affordable and widely available. Consumers have benefited greatly from reverse-engineered computers and smart phones. Even the IBM PC was an Apple copycat in some ways.

I guess it’s a delicate balance to design a system that rewards invention but still gets those inventions to consumers affordably.

It’s not really about rival states or regimes either, although it does happen more readily when there’s national borders and ideological chasms between them and your ability to litigate.

American corporations for example will blatantly copy your thing, then wait for you to sue, if you can. If you don’t, they’ll continue to sell it, and if you do they buy you out. They’ve calculated the exact risk of a buyout or a punishment, and come to the conclusion that on average it’s cheaper to cheat now and apologize later. If there was no patent law, they’d just steal your stuff every day.

Like insurance a patent ISN’T protection, it simply means you can take a rich corporation to court, spend all your money to defend your rights against them and still, probably, loose. We have the best “justice” system money can buy, and always does.

Makes you wonder how many other patens have been stolen and are on cars today where the inventor didn’t have the means to go after the money.

Dear Developers of Europe and Germany in particular,

It is urgent to get out of the forest again, the third attempt to get EU software patents through is happening now.

Software patents are a danger for small companies that cannot afford defense, especially against patent trolls. The UPC is was an international court located outside of the European Union (EU) and outside of the realm of the European Court of Justice (CJEU). This patent court would have had the last word over software patentability, and patent law would have operated in its own bubble.

https://ffii.org/eu-software-patent-court-stopped-by-constitutional-court-patent-industry-will-try-again/

We need the Germans to wake up and shake the Bundestag to refuse EU software patents once again like they did in 2013, and send back the bill for renegotiations, it will be required anyway with Brexit (they need UK-FR-DE to get it running).

Many years ago in the days of VHS, I worked at a company that produced a device that removed MacroVision copy protection. Despite such a device being legal in itself, we nonetheless did get a cease and desist for patent infringement. MacroVision also held various patents on sensible ways of /removing/ MacroVision. I remember thinking that was pretty clever of them.

Doesn’t a patented invention have to have some utility? What’s the utility for that, apart from pirating tapes? I’m sure YOUR company didn’t apply for any patents. Doesn’t the utility have to be legal? Or was tape copying a civil law thing?

At the time Macrovision defeaters were generally advertised as recording “improvers”, to fix weak or damaged sync signals on tape by generating syncs with proper timing. They would come as a box you’d put in between the composite output of the playback VCR, and the input of the recording one.

To summarise (IIRC) a Macrovision’d tape’s video signal had loads of extra H-sync pulses along each scanline, after the actual, first, one. A TV wouldn’t pay attention to them, only syncing up to the first H-sync on a line, then drawing that line of picture. Then after that, waiting at just around the time for the next one due to arrive.

A VCR would, though, and would keep trying to re-sync along the scanline. So the recording VCR, out of the pair you were using to duplicate, would record a messed up sync onto the copy. This then wouldn’t play back at all.

So, the defeaters would wait for the first pulse, like a TV would. But any further pulses were blocked, up until the proper moment another genuine pulse was due. It would let through only one H-sync pulse per horizontal line, at the beginning.

In the process you could argue it shored up the timing a bit more accurately, it’s intended “legitimate” purpose. They were just a few monostables and a bit of gating, AFAIK.

So… did Macrovision’s Macrovision-removal patents play along with the pretense of being “sync improving” devices or were they flat-out patented as pirate-helping Macrovision strippers?

The devices I saw advertised were always mail-order anyway, in magazines for satellite and video enthusiasts. They were never gonna be glaringly legitimate. I’d have thought a company would make up a batch and then just use a new company name each month, selling them in fairly small numbers. The real money was surely in pirating the tapes anyway. There must’ve been a few quid, for the holograms and stuff that film studios started sticking on the cassettes of legit ones.

A patented device doesn’t necessarily need to have any use, but it has to work in the sense that you can’t patent a device that breaks the laws of physics or just doesn’t do anything.

35 USC 101 reads: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and ***useful*** process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and ***useful*** improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” (emphasis added)

There’s also design patents.

In the patent lingo, “useful” means that something can be used and it works – for example a motorized soup spoon may be “useful” as far as it successfully spoons soup into someone’s mouth – but for the point of being actually useful as an eating implement, that’s not a concern for the patent. It has to work, but whether it works well enough to be of practical use is of no concern.

“Sync improving” was a fig leaf, but it was a pretty thick one. In those days older TV sets (think no solid state components, entirely vacuum tube based) were still fairly common, and some of those choked on the macrovision signal distortions. Of course everyone knew the real purpose, so by patenting the techniques that might be used to undo the distortions they’d deliberately introduced, they were patenting those techniques even if you were using them to “improve sync” for your beloved 1968 era TV set.

You are correct; the devices themselves were legal and the use for the purpose of enabling backups of legitimately owned media as well as for cleaning up the video signal is fine. But yes they can and were also used for piracy, which is not a legal activity, but that is separate.

You understanding of how they work is pretty much correct — MacroVision added specially constructed noise that made the recorders’ AGC circuit go wonky. You would usually still get a copy, but it would be quite unpleasant to watch. The removers gated that noise out — it was pretty easy. There were a boatload of designs folks made – one of my later ones used the LM1881 to essentially just regenerate all the sync signal (and I think there was also some filtering around the color burst).

Yes, it was definitely a grey market. This company was a mom-and-pop cottage business, but at the peak we were selling about $ 90K USD per month of these things alone, so it was compelling business.

Made in America by Bill Bryson. Several interesting stories about patents.

These patent abuses apply to large computer corporations like MS, phone companies, etc.

An example is the compression in MSDOS6. The company that developed the compression discussed this with MS and a royalty was discussed. Then MS just took the concept and released it without paying for it. Long court case and MS counter-charged that their software was decoded to prove their own breach, and this reduced the payout. It was a clear cut case of theft, but the payout was insignificant to what they made out of it.

Only the lawyers win as they make from both sides. And the judges are ex-lawyers so they just help their mates by prolonging the cases. It’s a corrupt legal system! You better have plenty of $ to bring, or defend, a case because the lawyers will end up with your $ even if you win!

the patent system – particularly the USA one – should just be deleted ie no patents for anyone. It’s now all about stopping innovation and big companies bullying smaller ones…

The guy who invented the bread bag clip carved his first one from an expired credit card on an airplane flight. He didn’t want to eat all of his bag of chips and wanted to keep them from spilling. The USPTO denied his patent application as too obvious, but they did grant his patent applications for the machine to make the clips and the machine to put them on the bread bags.

Spiral sliced hams had a start similar to intermittent wipers – except the big meat processing companies weren’t faking disinterest while secretly developing their own method. The inventor just couldn’t convince anyone that sliced and cooked ham on the bone was the best thing since sliced bread.

So he patented his invention and established a company to buy, cook, spiral slice, and market hams. Huge success! *Then* the big processors came to him, hat in hand, begging to buy spiral ham slicing machines. The inventor essentially told them to shove off, they had their chance when they could have licensed the rights to the concept. So until that patent expired only one company was making precooked spiral sliced hams.

It’s interesting to see the comments from the readers regarding obviousness 43 years after it was patented.

Transistors has only been invented a few years earlier.

The patent was filed shortly after the 1st astronaut launches. Flying to the moon wasn’t obvious then.

It’s easy years later to be confused as to what’s obvious.

Have they considered the 26 auto defendants questioned the obviousness & prior art including Amos and about 300 others.

We prevailed over every argument.

At the time of the Ford trial the most the industry paid for inventions was 12 cents a piece. By the time we went to trial with Chrysler inventors were getting up to $2 each.

RC delays worked with valves / tubes too, not just transistors. It’s a basic delay circuit.

Choosing a transistor over a valve would be a no-brainer, transistors work with the low voltage and high current used in cars, and they can take much more of a knock than a glass tube full of vacuum. Transistors would be the only viable method.

The idea, as I understand it here, was to use an electronic delay circuit, to perform an electronic delay. Your dad didn’t claim the idea of delaying wipers altogether, did he? Just using electronics to do so. A basic timer circuit of the same type used in countless other applications at the time. No flash of inspiration or genius, no novelty, any electronic designer would have used exactly the same method if he’d decided to build an electronic wiper delay.

I wasn’t at the court, but I’ve a feeling the general public’s ignorance of science and technology might have been the winning factor.

The circuit in question is the equivalent of phoning NASA and asking them “have you considered some type of rocket?” to get to the Moon.

>Transistors has only been invented a few years earlier.

The FET was actually invented and patented in 1928, and a similar device in 1934 in Germany. They just couldn’t make field effect transistors work right until the 50’s because of the lack of metallurgy. The BJT was actually invented to bypass the earlier patents of the field effect transistor! The field effect was already known, so the company patent lawyers recommended Bardeen, Brattain, and Shockley to make it work some other way.

They got the credit for inventing the transistor, but what they actually did was invent a way to make A transistor – not the device itself.

Yeah right … like this one: [https://patents.google.com/patent/US10144532B2/en]

https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/research/a30645682/navy-ufo-patents-compact-fusion-reactor-inventor/

This article is as a great follow-up to the film “Flash of Genius.” Films about inventors / pioneers struggling with automobile industry convention regularly have appeal as recently shown by Ford v. Ferrari and previously in films like Tucker. Perhaps now I will find the DeLorean biopic and the Harley Davidson series.

The Coronapause has given me time to fix the horrible, monstrous setup whereby when you attempt to wash your windshield, instead the wipers activate and spread whatever is on there into a totally opaque film, and after you are blinded, a small squirt of fluid goes on the windshield.

I also use RainX – Crystal Fusion – the other anti-surfactant coatings so normally water just runs off at any reasonable speed, but there are times the bugs seem to be kamikazes to my winshield.

My truck has Aux switches, and now (with a separate pump) I can saturate the windshield to the extent I want first.

Wasn’t the first intermittent wiper based on a hot wire expanding and closing a contact? Which is exactly how all turn signal blinkers worked at that time (prior art). Bulb burns out less current faster cycle. I remember hearing the hot wire wipers patent story on NPR years ago. Simpler than any RC circuit. A wirewound resistor rheostat adjusted the time interval. A piece of Nichrome wire, a stamping of thin metal, and hollow rivets in a chunk of molded plastic, chachunk and done, no transistors etc.