This collection of public domain books proclaims to not be about survival, but for survivors. It is a extensive collection of text books, manuals, etc., in over 150 categories from Accounting to Woodworking. Because of the copyright duration laws, most are around one hundred years old.

You might not want to have your appendix removed by someone who has only learned surgery from reading Dr John Sluss’s 1908 tome, “Emergency Surgery for the General Practitioner, with 584 illustrations, some of which are printed in colors“. But some knowledge is timeless. And much is of historical interest as well, helping us get a better appreciation of what bodies of knowledge people had in the beginning of the last century. There are books on farming, forging and casting, steam engines, clockmaking, telegraph and telephone, and even back issues of Scientific American and 73 magazines, just to name a few.

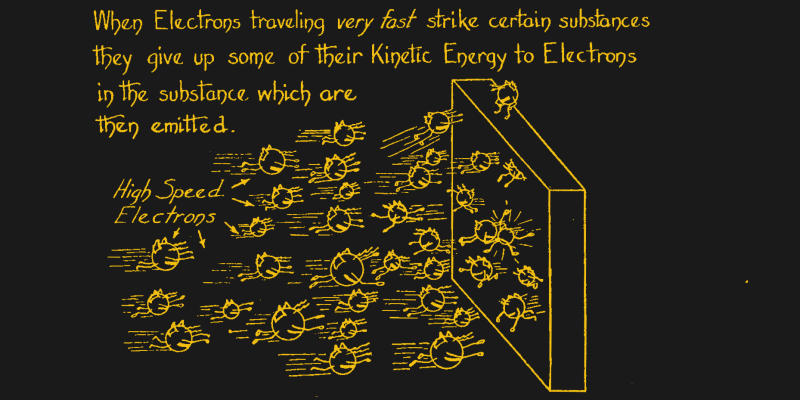

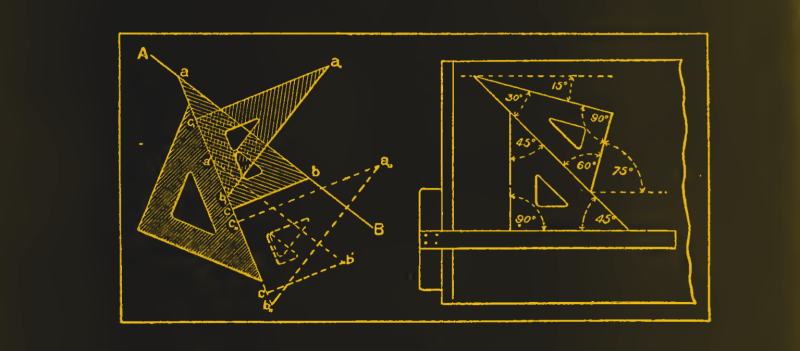

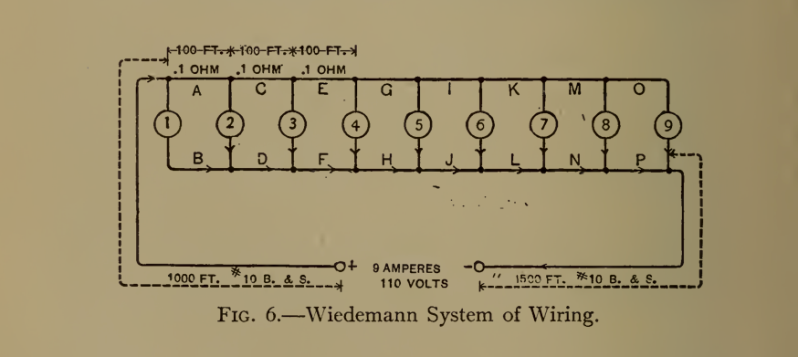

Here’s a random sampling of a few illustrations from electronics-related books.

High speed electrons from “Inside the Vacuum Tube” by John F. Rider, 1945, a relatively modern book from this collection. This book alone is worth downloading just to see the excellent illustrations. Mr Rider wrote so many technical books that he formed his own publishing company.

Using triangles from “Mechanical Drawing, Prepared for the Students of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology” by Linus Faunce, 1898.

The Weidemann system of wiring lamps, from “Electric-Wiring, Diagrams and Switchboards” by Newton Harrison E.E., published in 1906, complete with “one hundred and five illustrations showing the principles and technics of the art of wiring”. This system employed equal lengths of wires between each lamp in a (failed) attempt to make the voltage drop the same for each bulb.

Do you have any timeless reference or text books you like to use? Let us know down below in the comments. And thanks to [David Gustafik] for the tip.

Another oldie but goody spot for public domain and other freely distributable licenses: http://www.freeinfosociety.com

Project Gutenberg has plenty of good non fiction: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/

And of course archive.org, using advanced search for material up to 1926-01-01, which will weed out the “alternative” garage bands and other clutter.

Sometimes, the older books are much better for learning about a topic than modern ones, and much more practical, in fact modern books are often seem to be written by people who never practiced anything they wrote about and have only read about it because they leave such gaping large gaps in knowledge.

Chemistry books are far better in the late 1800s and 1900s, the heyday of discovery when the Germans were really much like the Americans were with the silicon chip industry in the 1900s. The chemistry books will often teach how to extract all the known elements (in inorganic chemistry text books) up to that time including the rare and ahem “controversial” ones. Plenty of discoveries in the organic chemistry realm too, invention of dyes, medicines, and other useful chemicals. Also plenty of knowledge on how to make the basic chemicals used every day with much more detail and “secrets” than modern texts, much more authoritative, though some processes have undoubtedly improved. That goes for agriculture too (with a few obsolete practices like treating seeds with mercury compounds), x-rays (it used to be possible for a boy to go to a street corner pharmacy and buy an x-ray tube just like one would a vacuum tube or an incandescent light bulb, can you believe that?), electroplating, and plenty of other “forbidden” and censored knowledge. If you want to know where all those fun experiments with electricity come from that you see in videos and physics books, check out Faraday’s Experimental Researches in Electricity, great weekend read. Physicists were once in a contest to see who could make the most powerful voltaic pile, it was a sign of credibility! Want to know the history of laughing gas and artificially carbonated water, then read up Observations on Different Kinds of Air by Joseph Priestley.

Books: they don’t make them like they used to. We need more people with practical knowledge otherwise, expect more empty shelves…

“Another oldie but goody spot for public domain and other freely distributable licenses: http://www.freeinfosociety.com”

Got a trojan warning, do I really need a condom?

Great illustrations and an interesting travel back in time. Also, finally a correct use of the word old ;)

Thanks for the post. Here’s a URL to Rider’s Inside the Vacuum Tube book.

https://worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/Rider-Books/Inside-the-Vacuum-Tube-Rider-1945.pdf

I didn’t have this book. Checking out the illustrations now.

Handy because…tubes never die.

When I was restoring antique electronics items I would have given my eye tooth for Fotofacts manuals on repair, but I understand that Sams Publications still hold active copyrights on those. Would really really really like a service manual for Silvertone wire recorders.

https://archive.org/

“Project Gutenberg” has been adding books since 1971 – https://www.gutenberg.org/help/faq.html#about-project-gutenberg

Neat list of books, but there seems to be no way to download them other than a slow crawl with wget. Seems reddit put together a torrent a few years ago, but that would be missing newly freed books.

There are various browser extensions or stand alone apps that’ll crawl through a website and download everything they come across, with filters as well.

wget or curl works, too. I’m doing that right now, and importing the list into my bookstack instance for offline reading/easier management.

combine wget with “make -j50”

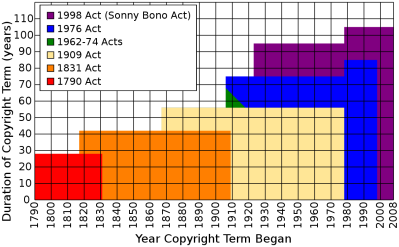

The copyright term extension graphic is also impressive.

A good illustration of why, perhaps, we might have overdone it.

You think?

Copyright was never about fairly compensating authors or protecting their moral rights, but about protecting the bottom line for publishers. Before copyrights, printing monopolies were granted by the king – hence royalties were paid to the king for the privilege of copying materials by print. It was also a matter of censure, since you would lose your rights by printing something offensive or subversive.

After copyright was introduced, the monopolies were lost. The publishing industry responded by arguing that the authors had the right to decree who has the right to print, which of course could be signed away for money, and that was the fundamental point of copyright: to secure back the monopolies on printing. The authors would then be forced to sign away their rights for practically nothing, since they could not afford to publish themselves anyways.

On the moral and ethical point of view, copyright is based on an idea of exploitation and cheating the public. Even if the author themselves exercises their law-given monopoly, it is still based on the idea that a work done once should be compensated a multitude of times, preferably forever, through artificial scarcity that has no justification, philosophical or practical. It is simply seeking to raise rent, which is basically living on the expense of everyone else. The big idea is to build up a portfolio of copyrighted works large enough that you can quit working and simply live off of the royalties. The only defense of copyright then becomes that people rarely succeed, which is not a defense at all.

So to the question, have we overdone it, the answer is simple: we should not have done it in the first place.

*After the monopolies were lost, copyright was introduced.

If patents lasted as long as copyright, we would not be communicating with each other right now using computers. Copyright was a misstep, imagine a carpenter or a welder receiving a payment every time someone sat on a chair they created for life +75 years (+100 if they were in Mexico).

Sorry +70 years after the death of the author in the US. (ref: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries%27_copyright_lengths )

And yet no one has an issue with mass production. You know? The idea of spreading the cost of creation across multiple copies and selling those. Oh like say the way we’re doing now with media.

>The idea of spreading the cost of creation across multiple copies

That has nothing to do with Copyright.

The idea of spreading the cost of creation across multiple copies should result in the price being zero, because there are no limitations on how many copies you can make once the work is already done. “Intellectual property” is immaterial, so any price you set per copy is unjustified because it immediately implies restricting the number of copies to be just so many.

You do not “mass manufacture” such works, because the actual work needed is always just for the first copy. Copyright is not needed to arrange for multiple payers or sources of funding for the initial work, and copyright is doubly unnecessary to handle the subsequent copies once all the actual work is already paid for.

An alternative to copyright is simply the rights of authorship: the right to protection of property against the theft or destruction of unsold and unpublished works, the right of protection against mis-representation or defacement of works, including the use of works in advertisement and propaganda or other social influencing, or falsely presenting the work as your own. Work for hire is considered the property of the commissioner as it is now, and the rights and responsibilities of authorship belong to the commissioner.

For example, a work that is exhibited for a fee, such as in a gallery or a theater, or a live broadcast of which a full copy does not already exist, should be considered unsold and unpublished and sneaking a copy of it outside of the “exhibition” would be considered illegal. A work which is already distributed in full copies, or by copies being made, would be considered sold and published by the act of producing and handing over the duplicates, and these copies belong to their receivers in full as given.

If anyone should use a piece of work for advertising or political campaigning etc. they must always sign an agreement with the author(s) directly for the duration and extent of use. Derivative works and alterations are always permitted unless they can be confused for the works of the original author, in which case an agreement must be made over their use with the original author.

The rights of the author end at their death or the end of legal personhood (such as for corporations having commissioned works).

I see nothing in any of your arguments about value to the receiver of the results of someone’s work. I think you are missing the entire point. In some cases the work represents a lifetime of research. What is its value?

What value someone gets from a piece of work, intellectual or otherwise, is not the business of the author unless specially agreed on. They are not automatically entitled to the value derived by other people, any more than the manufacturer of a hammer is entitled to the benefits of someone else’s house built with it.

If you want to talk about objective value, the real value of anything is exactly the resources needed to maintain its means of production. Any price paid above that means giving people money just because. You may ask for such profit, but nobody is entitled to more than they are due. We may give such profit out of gratitude and appreciation – or because we cannot obtain the article otherwise – but not by command or law. The entire point of a free market economy is that free competition should make the prices approach the cost of production.

Speaking of which: a “lifetime of research” implies it was already paid for. One does not spend a lifetime not eating or wearing clothes. The compensation for spending a lifetime researching something is that now you know it, and may use your knowledge to produce something valuable you can actually sell to other people. Again, if you spend a lifetime inventing a better hammer, you are still not entitled to the benefits of someone else’s house built using it.

Also notice: the cost of production for anything that involves human labor, intellectual or physical, obviously contains the cost of living for the person.

The argument of “due compensation” and “value of a lifetime of research” is begging the question that it’s up to the person making the argument to choose which kind of work should be valued, and how. It is holding the work of an artist or an author valuable in itself without considering its social and economic context.

The reason why we (try to) have a free market is because nobody can decide or dictate what level of living one should have. We let supply and demand decide it, so people whose work is in great demand should live large, and people whose work is in low demand will struggle. This should direct people to choose occupations which are generally useful, not simply what they want to do, or what is easy to do. There are various reasons why this does not entirely work, but those are not arguments for giving some people arbitrary rights to cheat profit out of the society as copyright does.

Yeah, I think you are lost in a logical argument instead of reality. A bit of pointed steel, a bodkin, was worth less than a penny in New England. It was worth a year’s labor in the drainages of the Snake and Columbia rivers because it increased the productivity of the owner by orders of magnitude. It replaced the piecing of hide with a bit of pointy rock, or bone or horn sharpened on a stone. Why would you ever judge its value based on the resources needed for manufacture? The value is determined by both people making a trade. Your idea has an economy without growth or change like the 10,000 years of tribal life in those very areas where people are willing to pay extravagantly for that big needle in order to change the cycle. I give you a pile of furs and my family can make clothing and tents and bags and ropes and all manner of things that will indicate great wealth and success and status where I live. Status is the most important in a tribal world.

>The value is determined by both people making a trade.

You’re just trying to muddle things by talking about different sorts of “value” as one. The idea of a trade is that each person trades up – according to what is more useful for them. As you can see, their measures of “value” over the same subject contradict in the absolute sense.

You cannot use subjective value to argue for any “fair compensation” in a general sense, only between the two people engaged in the trade. You might attempt to define value for other parties by saying “If you had to pay, how much would you?” and then taking some sort of “average utility” estimate to find out how much the society should owe the person, but then that is begging the question that I have to pay to make an argument that I have to pay because there exists a price I would pay, if I had to pay – which is perfectly circular!

>Your idea has an economy without growth or change

On the contrary. It’s the work of others to build on an idea, and it is that work which earns the value that comes out of it. It is this value added to value through work that is growth. There is no limit or end to what value you can project into the future, and it is also unknowable; it is absurd to give one person a monopoly to all that, especially when it is not actually their doing any longer that any of that comes to be.

If everyone had to pay somehow according to all the value they derive after the fact, the person who made the invention should then also pay backwards to all the people whose shoulders he’s been standing on, to the point that you’re piling money on the grave of Newton or the first caveman who invented fire.

Or to put it more simply; if I like a painting you made, I can say I find value in it. However, did you make me like the painting? Did you create that value – or did you just create the painting?

If you had no input in what I find valuable, then why should I pay you any extra for it? What do I owe you for something I do?

“On the moral and ethical point of view, copyright is based on an idea of exploitation and cheating the public.”

Oh darn, I feel so exploited reading HaD. Here’s the thing, we’ve already decided as a society to outlaw slavery in all it’s forms. That means we can’t make authors work for us, turning their efforts over without due compensation. Society recognizing that bit of truism has a compromise where a limited monopoly is granted that will benefit both parties.

Copyright has nothing to do with duly compensating authors for their work, it has no mechanism to make sure any compensation is paid in the first place, and the absence of copyright does not in any ways imply authors must work for free.

If you do not feel exploited by copyright, you simply do not understand the extent of the problem. You are constantly paying to support people who literally do nothing, because of a legal fiction that enables these people to extract money out of the economy without producing any new value for it, and for the most part they aren’t even the authors who originally did the work but simply corporations who obtained the rights.

To put things into perspective, Hollywood makes more out of copyrights and royalties than the entire agricultural sector of the US that makes all the food you eat.

How pays these people for something with no value? And why? Are they in government?

True, true.

>How pays these people for something with no value?

The classic example is a land owner who has a river crossing his property. The land owner puts a chain across the river to extract tolls from any boats on the river, which means earning money by extortion rather than by adding value to the land or the river. In other words, the land owner earns money simply by returning to use what was already freely available, which is literally getting paid for nothing.

The point of making money through copyright is exactly that.

In some senses, the land owner in the example is getting paid for negative value, since they’re slowing down other commerce and inconveniencing people by their toll collection, so they’re harming the economy in two ways: getting unjust compensation, and causing inefficiency.

Likewise for copyright. Many labor hours are wasted in trying to figure out whether you can or can’t publish some work because it contains copyrighted material, obtaining the rights or licenses, in the employment of lawyers, prosecuting people, moderating online media for infringement, policing people and invading your privacy…

> we can’t make authors work for us

Copyright does not ensure due compensation to authors, and the absence of copyright does not imply authors must work for free or otherwise. You are simply confused.

For example, let’s say you are a comic artist drawing a superhero comic for one of the famous publishing houses. Your work is for hire, so the copyright belongs to the house, you get paid $100 a page and that’s it. The publishing house then gets to charge $5 per issue and sell millions of copies; you will never see a cent of that money. The limited monopoly benefits only the publisher.

Even if the money was shared between the author and publisher, or taken by the author alone, it’s still not going to “duly compensate” the author. Why? Because there is no connection between the work that was done, the amount paid per copy, and the number of copies sold. No proper contract between the author and the customer is possible. The customer has no knowledge of how many others are paying or how much work was put into the original, so they have no rational means to figure whether they’re paying too much or too little. The whole market is based on the exploitation of ignorance.

For this reason, it is necessary to maintain the myth that copyright and sale by copy or by subscription etc. fairly compensates the author – in reality they’re just gambling to see if people are stupid enough to pay whatever you ask them. The whole point of the scheme is that the people who pay do NOT know this, so they would pay a dollar where they would reasonably pay a cent.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, all copyright should be 27 years from first production and then it’s totally in public domain.

If copyright must exist, it should work exactly like patents. If you want the rights, you have to pay for it, and the period is 20 years from filing or 15 years for “design” patents, which would be the closest equivalent to works of art.

If you intend to make money by special privileges granted by the society, then you should pay the society for extra costs and damages incurred by your doing so. The average cost of a patent is something like $6,000 – $12,000. Applying the same for copyright means you’d have to think hard before copyrighting absolutely everything imaginable, because most of the things you would copyright would never return the investment.

However, putting a price on copyright does not solve the fundamental problem: gains through an artificial monopoly are still unearned and unjust. Pricing a copyright according to the average market value of such privileges would still leave large corporations at an advantage, and individual authors at a disadvantage because they can’t effectively leverage or protect their copyrights. The right solution is simply to grant no copyrights.

Wow, fantastic list, thanks for this. I will have to spend some time and go through it.

I didn’t see Kempe’s ‘How to Draw a Straight Line’ treatise on mechanical linkages. As the eponymous title suggests, it’s about drawing (or cutting) straight lines from first principles: It’s on Project Gutenberg:

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/25155/25155-pdf.pdf

I made a number of the mechanisms in it from Lego Technic, plus a felt pen and pieces of paper.

“You might not want to have your appendix removed by someone who has only learned surgery from reading Dr John Sluss’s 1908 tome, “Emergency Surgery for the General Practitioner, with 584 illustrations, some of which are printed in colors“” The human body hasn’t changed that radically in the last century (just gotten fatter) and the surgical techniques for removing an appendix 100 years ago were quite good, so if care is taken with cleanness I think you’d be better off getting your appendix whipped out by someone with Dr. John’s book and an xacto knife than dying or peritonitis.

Great point Hirudinea. Yeah, when I wrote that sentence, I was thinking more about 100+ years of improvements in surgical techniques and tools, not that the body has changed.

Reminds me of http://www.survivorlibrary.com/

Does anyone know what Happened to the freeinfo site?!? I’ve been a fan for damn near 15 years it seems, and a month or two ago I attempted a visit only to find the site no longer exists?!? Found this thread by trying to look into its closure; i am 100% butthurt.