Aviation history is a bit strange. People tend to remember some firsts but not others and — sometimes — not even firsts. For example, everyone knows Amelia Earhart attempted to be the first woman to fly around the globe. She failed, but do you know who succeeded? It was Jerrie Mock. How about the first person to do it? Wiley Post, a name largely forgotten by the public. Charles Lindbergh is another great example. He was the first person to fly across the Atlantic, right? Not exactly. The story of the real first transatlantic flight is one of aviation hacking by the United States Navy.

The Quest for a Flying Boat

Airplanes really got their start with the Wright brother’s flight in 1903 — even though you can make the case for some earlier flights — and by 1914 there was already talk of taking a flying boat across the Atlantic. However, the engines of the day weren’t that reliable and the plane had to be able to lift enough fuel to make it between refueling points. That limited the choices of places to take off and land.

In 1914, a British philanthropist had Glenn Curtiss built a flying boat with a 72-foot wingspan, mounted three engines, and called it America. It was supposed to fly the Atlantic, but with the onset of the Great War, that never happened.

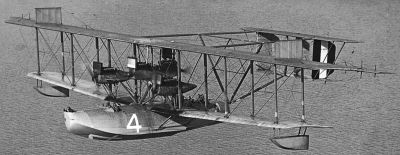

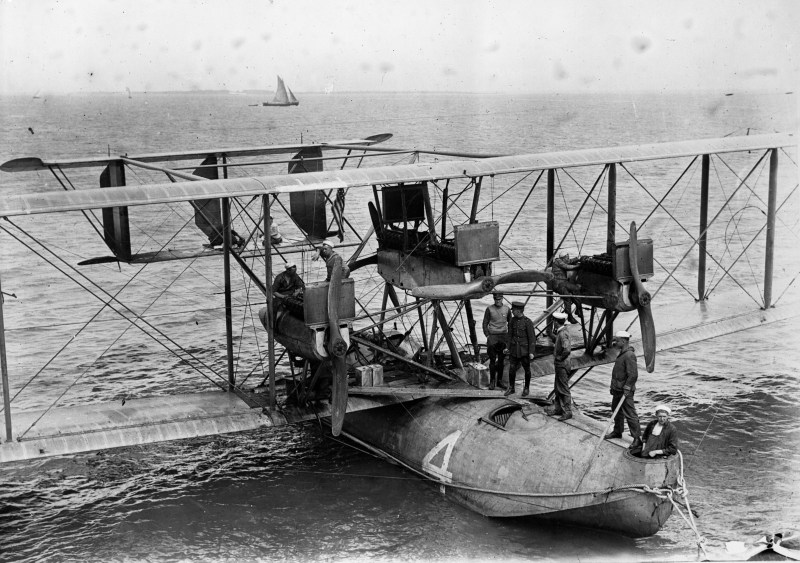

The United States also wanted flying boats during the war, mostly for antisubmarine warfare. In 1917 the Navy and Curtiss decided to produce the NC or Navy-Curtiss flying boat, commonly called Nancies. This was a big plane for its day at 69 feet in length with a wingspan about the same as the 108 feet of a Boeing 727. By 1918, the first 12-ton Nancy made its maiden flight.

Across the Waves

The Navy decided that three NC flying boats should cross the Atlantic. Of course, sending a plane across the Atlantic today isn’t a big deal, but in 1918 this was equivalent to announcing you were going to the moon in 1969. Future president and then assistant secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt was a major supporter of the idea of a flight. But flying was only one part of the bigger puzzle.

Richard Byrd, another name you might know from history, was also involved in the project. He would later become famous for polar expeditions, but during the war he had developed tools and techniques to improve navigation while over water. In particular, he worked with the bubble sextant. Ships use the horizon when measuring with a sextant but airplanes need a different means since they are elevated above the surface and not finding a natural level on water. A bubble sextant provides an alternative to the natural horizon to measure from.

Byrd also employed drift indicators that used a reference point on the ground to determine how far the plane was drifting. Both of these would be useful to planes trying to cross the ocean. While he didn’t get to actually make the flight, he did help in the planning.

What a Plan

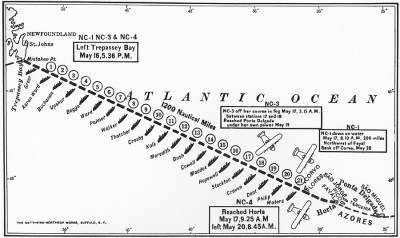

To help ensure success, the Navy posted 61 ships roughly every 50 miles along the route to help with navigation and to rescue the crews, if necessary. That’s amazing when you think about the logistics of lining up 61 ships on a precise path.

Three flying boats were to participate. NC1, NC3, and NC4. The NC2 had its wing removed to repair one of the other planes. The planes also got an extra engine and super-efficient propellers based on the equations developed by engineer Charles Olmsted. These propellers were 20% more efficient than conventional ones. So you’d think with all this support the three planes would make it across with no difficulties. But it wasn’t that straightforward.

The three planes departed Rockaway (part of New York City) on May 8, 1919 to head for Newfoundland. NC-4 lost two engines and had to land in the ocean near Cape Cod. The aircraft acted like a boat for five hours to reach the naval air station at Chatham. The other planes landed in about nine hours, but NC-4 didn’t catch up until May 14th. The press speculated that NC-4, practically on its maiden voyage, was a lame duck and would be left behind.

There was another problem. The new propellers were cracking on all three planes. The decision was made to go back to the standard ones.

Leaving Newfoundland

The two planes, NC-1 and NC-3, tried to depart on May 10th without the NC-4, but were too heavy to lift out of the water. Once NC-4 rejoined the trio, they tried again, successfully, on May 16th.

The navigation instruments were poor, but they did have the string of Navy destroyers every 50 miles to light the way. NC-3 had an electrical failure and the planes separated from formation to avoid hitting the dark plane. Once fog became heavy, it was difficult to find each other or the ships visually. However, the pilot in NC-3 sighted a destroyer that was not part of the navigation line and thinking it was one of the ships guiding them to the Azores, corrected course.

Eventually, it was apparent he should be close to the Azores, but couldn’t find the next ship. The plane set down in rough waters which collapsed an engine strut, grounding NC-3. NC-1 also landed to try to get a position fix and, while undamaged, the seas were too high for the plane to take off again, effectively ending its mission.

Making It

That left NC-4, the lame duck plane that almost didn’t get started. It was also the fastest of the three planes. It cut through the fog, the crew fighting disorientation. They knew from a radio fix and dead reckoning that they were close to their destination. Finally, a break in the fog let them glimpse one of the islands and that information led them to find a suitable harbor to land in. The lame duck had made it.

NC-1’s crew was taken off by a Greek freighter. It eventually sunk beneath the waves. NC-3, however, was missing for a few days. To reduce weight, the crew had stripped out nearly everything from the aircraft including the radio transmitter. Unable to take off in rough seas, the crew used the tail of the airplane as a sail and went over 200 miles tail first to sail to the Azores. While not an aviation first, it was dazzling seamanship.

Forgotten

The crew of NC-4 — Albert Read, Walter Hinton, Elmer Stone, James Breese, Eugene Rhoads, and Herbert Rodd — are in good company. No one remembers Wiley Post or Jerri Mock, either. Later in 1919, Alcock and Brown flew a biplane from Newfoundland to Ireland, winning £10,000. A few weeks later an airship made the crossing and even carried a few passengers.

As you can see at the 6:33 mark in the video below, Read and Rhoads would duplicate their flight in 1949 much faster in a contemporary aircraft. There’s also newsreel footage there from the 1919 flight.

Why do we remember Charles Lindbergh? Well, he flew nonstop and landed on the European mainland. Everyone else hopped from place to place like the NC-4 did. He also benefited from great press, a different public sentiment about flying, and that he flew alone. The tragic kidnapping of his baby after the flight also cemented him as a public figure. Then, too, he was an inventor, but the world seems to have forgotten that for the most part.

Earlier, we talked about technical audacity. Flying a 1920-era airplane across the Atlantic would seem to qualify. Those early pioneers developed techniques and learned lessons that would help make transoceanic flight commonplace very quickly. Yet we scarcely remember who they were.

Lindbergh is specifically credited with making the first _solo_ flight across the Atlantic, not the first flight or even the first nonstop flight. What made it remarkable was that he was alone in the plane and unescorted, so he would have been in a very bad fix if his aircraft didn’t perform exactly as he expected. Which, if you think about it, makes Lindbergh’s flight a lot more like going to the Moon in 1969 than the flight of the NC’s.

+1

There was a simple reason why it was such a feat. Engines of that time couldn’t run for extended periods of time (reliably) because there were no detergents in the engine oil to wash off particles and burned residue, and keep them suspended in the oil. If the engine did run badly, it would soon foul and break.

A cupful of “motor up” would have made the whole attempt trivial.

> Why do we remember Charles Lindbergh? Well, he flew nonstop and landed on the European mainland. Everyone else hopped from place to place like the NC-4 did. He also benefited from great press, a different public sentiment about flying, and that he flew alone.

And three years after Lindbergh, Maurice Bellonte and Dieudonné Costes for the first trans-atlantic flight in the other direction (which is a little bit more difficult because or winds)

Beryl Markham first person flying solo east to west across Atlantic.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_with_the_Night

Lindberg’s autobiography “We” is a very interesting and worthwhile read.

The Azores is still about 870 miles away from crossing the Atlantic to Portugal, and it’s 1380 miles from Newfoundland to the islands, so technically they flew 61% of the way across. They tried to finish the last leg three days later, but had to turn back, and spent four more days repairing the plane

It’s kinda like saying “I ran the marathon”, when you did 16 miles on day one, and then finished the rest a week later.

And the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic was made by John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown literally the next month.

>Later in 1919, Alcock and Brown flew a biplane from Newfoundland to Ireland, winning £10,000. A few weeks later an airship made the crossing and even carried a few passengers.

NC-4 finally made it to Lisbon on 27 May, and Alcock and Brown landed on Ireland on 15 June, little over two weeks later.

The reason why they won the prize was because they made the trip within 72 hours while the NC crews took too long to qualify. Flying non-stop was not required – they could have stopped to refuel, but simply didn’t need to.

In my opinion the NC-4 was the first by a technicality only, since the same plane eventually got across by flying. The prize rules also specified “only one aircraft may be used”, which was to stop contestants from pulling off a pony express stunt. The week spent on rebuilding the engines at the Azores broke that rule in spirit, because the main challenge on the way was engine reliability.

Point being, “Later in 1919” makes it sound like it was much later, with lessons learned and improvements made, but that was not the case.

This is again one of those Dumont vs. Wright cases where the title of the first is debatable because they didn’t do it properly and unambiguously, and the winner depends more on the fact that the NC-4 team was American while Alcock and Brown were British.

Everyone knows that Wiley Post died in a plane crash taking off in Alaska. It also killed his passenger, Will Rogers, humorist and member of the Cherokee nation.

Jimmy Stewart played Lindberg in the movie “Spirit of St. Louis”.

Amelia Earhart was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. But since she later disappeared she is remembered for that, and maybe remembered more than the others.

I best remember Richard Byrd from his book “Alone”, about the winter he spent alone and almost died from carbon monoxide poisoning.

Alcock and Brown, references below.

http://www.aviation-history.com/airmen/alcock.htm

https://www.pistonheads.com/gassing/topic.asp?h=0&f=210&t=689460&i=1480

It’s interesting that most US citizens don’t seem to be aware that Brits were the first to cross the Atlantic in one flight.

Not to criticize Americans but they tend to have an insular attitude, love to make legends up about themselves and believe those legends without question. That’s why if you asked the average American who invented the car, the light bulb and who was the first to fly across the Atlantic they would say without hesitation Henry Ford, Thomas Edison and Charles Lindbergh. Americans are wonderful people but they just don’t seem to know as much about the wider world as you think they would.

You can’t really single out Americans for having that kind of attitude, it’s as present in the French, British, Chinese and Japanese. Heck even us Canadians have some of it.

Lindybeige also had a good retrospective of their flight: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yk56nBcSalg

Actually Wiley Post is still remembered. He developed the world’s first P-suit for his efforts to take his plane further and further up. In fact that design did not work at all, but it paved the way for better ones today.

I remember him because my grandfather was a pilot who got to fly with Post a couple of times, so I have his autograph in granddad’s logbook.

Post also discovered the jet stream, and was the first person to fly around the world solo. (Well, with a navigator, but he was the only pilot.) At the time he got the same reception/publicity Lindbergh did.

correction after reading his wikipedia page: he was the first person to fly solo full stop. He did it first with a navigator, then built an autopilot and redid it on his own.

Good to know.

Oh and Glenn Curtis did all of his plane building from a factory in upstate New York, in Hammondsport in fact, that was the basis for the original Tom Swift series.

Nah, attaching a boat to the bottom of your airplane is cheating.

“The two planes, NC-1 and NC-3, tried to depart on May 10th without the NC-4, but were too heavy to lift out of the water.”

I don’t follow this part, what does have NC-4 missing make the other two planes “too heavy to lift out of the water”? I feel I’m missing something….

Could be they were in different places. Sometimes sea planes have a hard time taking off if the water conditions are too smooth (harder for them to break contact with the surface). Also, planes of identical design often perform slightly differently especially back in those days when they were all hand built.

They were going to leave without NC-4. But they were too heavy and had to give up. By the time they tried again, NC-4 had arrived and they all left together.

I had the same thought as [irox], but I figured out what you meant in the end. It was written a bit confusingly.

Ah, the inability to take off had nothing to do with NC-4 not being present.

Thanks!

Francis Chichester wrote a fascinating account of his adventures in a Gypsy Moth biplane. He survived many traumas to himself and his plane. It’s a worthwhile read.

He went on to be the first person to circumnavigate the globe single-handedly on a boat, which he named Gypsy Moth.

Another heroic long distance flight was documented by Francis Chichester in ‘Alone Over The Tasman Sea’ where he piloted a Gypsy Moth seaplane solo from New Zealand to Australia in 1931.

If you want to see the actual NC-4 it’s at the National Naval Aviation Museum at the Pensacola Naval Air Station in Pensacola, FL https://www.navalaviationmuseum.org/things-to-do/aircrafts-galleries/

Being an international reader, and given it’s it’s something of a technical site, can you make *some* kind of effort to use SI units?

WTF is a foot even?

“The metric system is the tool of the devil! My car gets forty rods to the hogshead and that’s the way I likes it.”

+1 I have found that a lot of US writers forget that the World Wide Web is actually an international thing. Unlike The World Series of baseball!

+1

I’ve found that often it’s a Brit or American making these complaints, pretending to be stupid to complain for the sake of complaining.

If you want to be an SI purist, then also forgo the litre, minute and hour. In here we measure pints in cubic meters!

It’s not that hard to convert and now you can just say Hey Google or Siri and get the answer, if you can’t do the math in your head….

Half of the hardware in our cars are metric and it’s no problem having another toolset to work with. Why is it such a big deal?!

Us older gents dont use mobile devices for anything else than talking on the phone.

Here’s what I find silly: it doesn’t matter what numbers they write in the article, you have no use for them. Whether it’s 1200 nautical miles of 2222 kilometers doesn’t mean anything other than “It’s a long way away”. Big number, big thing. That’s all you need to understand for the point of the article.

People confuse knowing things with understanding things, but in reality if you go on the street and ask someone how long is a kilometer in real terms (or a mile for that matter) even in metric countries they have no idea. Ask them to walk a hundred meters and the end result will be more or less random. Some will follow the rule of “two steps a meter” and if you’re lucky they end up pacing yards, which isn’t that far off. Some will cheat and remember that street lights are installed 25 or 50 meters apart, except when it’s 30 or 40 meters.

Same thing with asking people to show with their hands how long is a meter – you get anything from 50-90 cm or up to 150 cm as some people will spread their arms all the way wide. Only some few know that a meter is the distance from your wrist to your opposite shoulder – for the average adult male. How arbitrary.

At least a foot is intuitively relatable and easily understood. It’s a foot. A few feet is something human sized, a couple dozen feet is something big you can walk around, and hundreds of feet is even bigger like a house. However, if someone says we’re flying at 50,000 feet or 15,240 meters, what do you do with that information? Unless you’re a pilot – nothing – it’s just a big number.

Also, why aren’t shoe sizes in Europe measured in centimeters, but in 2⁄3 cm “Paris point” which is a close approximation of 1⁄4 inch?

Only the Soviets used to measure peoples’ feet in metric units.

the Japanese measure shoes in centimeters, but I’m not sure Communism ever took off over there

Is Japan in Europe?

Ski boots seem to be measured in centimetres, even in the USA. I wish centimetre shoe sizes were more widespread.

I really have have no clue what a foot is, much less a 72-foot wingspan.

I’m not sure how you’ve come to the assumption that a foot is ‘intuitively relatable’

So you’re saying you don’t personally have feet, or know of anyone who has?

How a “foot” used to be defined, you take 16 men of the village, line them up heel to toe, measure the distance with a string and then divide by 16 (halve four times). A foot is literally a foot, albeit modernly it’s a rather large foot, but that doesn’t matter for the illustration and intuition of scale.

If you can’t wrap your mind around what a foot is, I seriously doubt you have any idea of what “24 meters” means either. At least you have a foot, even though it’s not exactly a foot, but where do you have a meter? You don’t – it’s abstract.

That’s why when people are asked to show how big a meter is, they rarely get it correct. Try it: take a tape measure and pull the tape out in your hands with the numbers facing away. Take out what feels like a meter and flip it over to see how close you got. People who sell cloth or install carpets etc. who might be dealing with meters every day might get it right instantly – most people are way off the mark. Try different distances, like how close you can guess 30 cm? This is much easier, because you’ve probably held a straight ruler in your hand many times. An A4 sheet of paper is this long. It’s about 12 inches, or a foot. Ironically, you already have a better intuition of a foot than a meter because you handle objects of that scale all the time. You just don’t call it by name.

If you have no concrete intuition of scale with a point of reference, then the numbers are just arbitrary and meaningless. Information without knowledge.

How about Clyde Pangborn, the first to travel non-stop across the Pacific Ocean? A wing-walking stunt pilot, he climbed out of the cockpit during the flight and sawed off his landing gear to reduce drag and weight. He also jettisoned everything of weight in the plane including his shoes. After reaching the coast of Washington he continued over 100 miles and over the Cascade Mountains, buzzed his mother’s house, and belly landed in Wenatchee. Pangborn Field is named for him.

Thanks for the name! Pangborn has a good biography on Wikipedia.