It’s dangerous for a hardware hacker to go into a second-hand store. I was looking for a bed frame for my new apartment, but of course I spent an age browsing all the other rubbish treasures on offer. I have a rough rule of thumb: if it’s not under a tenner and fits in one hand, then it has to be exceptional for me to buy it, so I passed up on a nice Grundig reel-to-reel from the 1960s and instead came away with a folding Palm Pilot keyboard and a Fuji 8mm home movie camera after I’d arranged delivery for the bed. On those two I’d spent little more than a fiver, so I’m good. The keyboard is a serial device that’s a project for a rainy day, but the camera is something else. I’ve been keeping an eye out for one to use for a Raspberry Pi camera conversion, and this one seemed ideal. But once I examined it more closely, I was drawn into an unexpected train of research that shed some light on what must of been real objects of desire for my parents generation.

A Thrift Store Find Opens A Whole New Field

The Fuji P300 from 1972 is typical among consumer movie cameras of the day. It takes the form of a film magazine with a zoom lens assembly on its front, a reflex viewfinder on its side, and a handle with a shutter trigger button on it protruding vertically below the magazine and also housing the batteries.

Surprisingly it still has a mercury cell that would have powered its light meter; a minor annoyance to dispose of this correctly. Sometimes these devices had clockwork motors, but this one has an electric motor. It also has a light sensor that is coupled to some kind of electromechanical aperture. It would have been an expensive camera when it was new, probably as much of a purchase as an SLR or a decent mirrorless camera here in 2021.

The surprise came when I opened it up, for it looked like no other 8mm camera I had seen. I’m familiar wit the two reels of a Standard 8 or the boxy cassette of Super 8, but this one used something different. That film magazine is made to fit a compact twin-reel cartridge whose film fits in a metal film gate. This is a Single 8 camera, Fuji’s entry in the all-in-one 8 mm film market, and a format I never knew existed. To explain my unexpected discovery it was necessary to delve into the world of home movie formats in the decade before videotape arrived and drove them out.

The Home Movie Days Had Their Format Wars Too

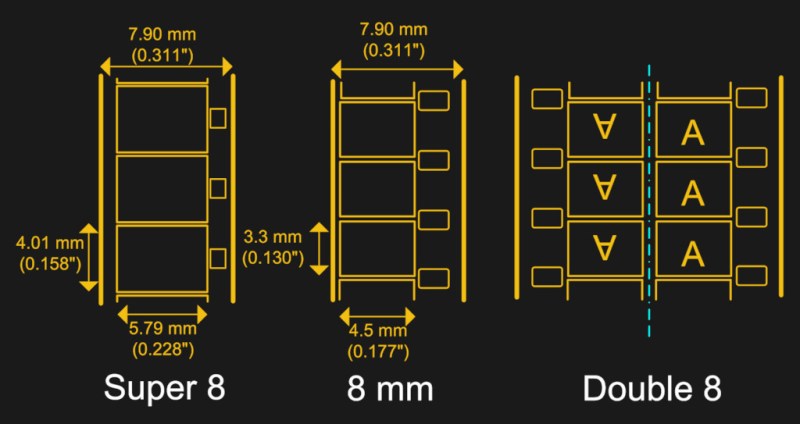

8 mm film dates from the early 1930s, when Kodak released the format as a cheaper alternative to 16 mm for the home movie market. The original 8 mm film, now known as Standard 8, is simply 16 mm film stock with twice the number of sprocket holes, which could be exposed on both edges by running it through the camera in both directions. The film strip would be cut in half and spliced together during development, resulting in a longer film strip with sprocket holes on only one side but with a short overexposed white section in the middle at the join depending on how successfully the user had kept the light at bay while swapping over the film reels. Starting in the 1960s, some manufacturers offered sound recording on a magnetic strip added between the sprocket holes and the edge of the film.

The shortcomings of Standard 8 with its inconvenient film swap-over, oversized sprocket holes, and unsatisfactory sound capabilities, led manufacturers to seek improved versions. Kodak’s Super 8 of 1965 had a larger picture area with smaller sprocket holes and sound capability designed in from the start, and came in a compact cartridge containing both reels one stacked above the other with no rewind facility. My camera’s Single 8 from the same year uses the same film format but on a thinner stock, and with separate reels. Arguments raged at the time over the relative merits of Super 8’s plastic film pressure plate over Single 8’s metal part, but reading around the subject, the consensus seems to be that both versions had a better picture quality that Standard 8.

It might be a surprise to some readers who are several decades on from their move to digital, that while Single 8 went out of production around a decade ago, both Standard 8 and Super 8 are still available — and have a significant enthusiast filmmaker following. Aside from the millions of simple home movie cameras like my Fuji, there were much higher quality professional-grade units, and these still command high prices. It’s attractive to pick up a Super 8 home movie camera and give it a go, but with film cartridges selling for around £40 (about $53) and offering only a few minutes of footage it’s hardly an inexpensive hobby.

A Teardown On A Device With Loads Of Tiny Screws, What Could Possibly Go Wrong!

This is the first time I’ve had a move camera on my desk, so it’s an ideal moment to dismantle it and take a look at its inner workings. And immediately I picked up the screwdriver it became evident that here is a very well designed and well built device indeed. Everything comes apart with very well-placed screws, and all screws are both easy to get to and turn as though they were last touched yesterday instead of five decades ago. Starting in the film magazine there’s a removable cover under the film cartridge below which can be found a gear train for the film advance, and a mechanism involving a PCB wiper switch for the film usage indicator. The motor drive is mounted in the handle alongside the batteries, with the same gear train driving both shutter and advance. For a Pi conversion there’s plenty of space for the Pi camera, but sadly the film pressure plate will need moving.

Turning my attention to the front, there is an aluminium cover that’s retained by two screws and the zoom ring on the lens. Some careful extraction of tiny grub screws deals with the lens rings, and the cover comes off to reveal the inner workings. The lens assembly has a mount casting that incorporates a prism and mirror for the viewfinder light path. This comes before the shutter, so it will be easy to retain in any digital conversion.

Below the prism is the aperture mechanism, as I suspected a tapered opening mounted on a moving-coil meter movement. The shutter itself is visible below the aperture mechanism, but I didn’t expose it, there should be a pair of rotating discs with openings in them. The surprise comes in how little in the way of electronics it contains: aside from the light sensor and moving coil, that’s it. This is a triumph of electromechanical engineering miniaturised into a handheld device, and as ready to shoot now as it was when first unpacked back in the early 1970s.

So do I have any guilt in tearing apart an 8 mm camera for a Pi conversion? If it were a rare or high performance camera then perhaps to do so would be a minor crime, but for a plentiful and mass-produced consumer grade item, and particularly one whose film hasn’t been made for years, there’s little chance of it being anything but a paperweight otherwise.

So with this one I’ll need to stop the shutter in its open position and remove enough of the film gate and pressure plate assembly to fit one of the smaller Pi cameras with its lens removed. There’s plenty of space for a modern battery in the handle, and I’m considering whether I can 3D print a facsimile of a Single 8 cartridge to house both Pi and sensor, thus minimising the dismantling required. These lenses give the same vintage home movie quality to digital images as they did to the 8 mm film when they were new, so I hope any videos I make will be suitably distinctive.

heh folding palm pilot keyboard with a serial interface. i believe i have the same unit! when my palm Vx died, i was able to hack it to work with my ipaq h3765 just as well. i still have the keyboard, and that ipaq actually still works (it’s plugged in to preserve its ramdisk, sigh) but i haven’t used it in about a decade. now i have a pile of garbage bluetooth keyboards with the one that actually works on top. i would not be buying another serial keyboard in 2021 thinking it might be useful in the future :)

Funny, i did almost the same. Found the Palm V keyboard second hand for pennies and made a custom adaptor that fit my Qtek (XDA) 2020 Smartphone connector. Oh, those were the times :D

I believe you’re missing an ‘i’ in ‘moving-col meter’

I hear if you read an article backwards, you can discover spelling errors better. Go for it. Report back.

Your attention of detail would make you an amazing coder.

Thanks! Fixed.

Jenny you think you have it bad. My wife works in a charity shop where they have no facilities for electrical goods.

They have a man that comes every so often and gives them a nominal sum per item.

So we get first dibs on everything electrical that comes in! Weekly bags of stuff needing not much fixing arrive at my workshop….

I used to fix (what I could) for a pawn shop.

Until I realized that once I fixed the stuff, I could no longer afford it!

I think I am lucky not to be in such a situation.

Interestingly, I’ve a related project sitting on my “to do” list but from the other end of the 8mm film lifespan – through my other half, who keeps, er, inheriting family antiquities (to put it politely) – the most recent tranche including about half a dozen 8mm film reels plus and ancient 8mm projector. No one (in her family) really knows what exactly what was recorded on them and I’ve yet to check if the project turns on (my first step is to at least see how electrically [un]safe it is before it even goes near mains).

Check it runs before loading film – if it doesn’t advance and the light keeps hitting the same bit of film there’s a risk of damage to the film or even fire. A colleague damaged a few seconds of old family film with a projector which wasn’t running properly.

Great advice!

8mm film will melt if it gets stuck in the film track but I don’t believe it will burn. Also even if it does melt splicing it back together isn’t hard (can be done with a razor blade) but it can be finicky. Good advice though.

This reminds me of movie theater film projection booths which, afaik, had to confine fires from old cellulose nitrate stock, before cellulose acetate replaced nitrate, afaik before WW II.

The interior walls and ceiling were probably bonded asbestos.

Fairly sure that even the ports in the front walls had drop–down shutters to confine blazes.

From what I was told years ago, the concrete shutters in front of the projectors would be suspended by wire going over the projector to a counterweight behind.

The projectionist would prepare each reel in advance, and start the new reel as the old one was running out. If they were leaning on the edge of the projection booth watching the film intently they might not notice a projector fire destroying the low-melting-point wire section holding the shutters up 😳

We had a projector, but for some reason an “editor”. Places for two reals, I can’t remember if it was hand cranked or motorized, and a tiny screen. I assume a film splicer.

I can recall my father using it, but other than maybe splicing the short reels from the movie camera together, he wasn’t making epics. It always seemed odd to have around.

We had the movie camera, a handheld light, a proper projection screen, and the editor. All of it used only for about 6 years, and forsome reason I never had an interest in it later.

And the camera had to be wound before use.

Ahh, spring–driven devices… telephone dials and acoustic 78(±) rpm phonographs…

These had big “mainsprings” (compared with ordinary clocks), multimesh speed–increaser gear trains, and a fast centrifugal brake, called a governor. Governors were silent, and needed no cooling. Speed control was Good Enough, except for timekeeping.

Windup toys had a crude speed limiter that made a characteristic sizzling noise. It had a fast wheel with triangular teeth and a rocker driven back and forth, akin to a non–locking lever escapement without any resonator for timekeeping.

Some windup toy cars had no speed

limiters. : )

Some windup cars were wound by holding them down and moving them backwards.

I’ll have you know I’m less than two decades on from my move to digital.

P.S. I bought an “as-is” 4-track from Japan on ebay (Yamaha MT100) that I’m slowly repairing. Bought quite a few “test” compact cassettes before I realized that a 4-track runs at double speed, and a 15 minute cassette is only 7.5 minutes per side, and therefor 3.75 minutes in this thing. Ooops, at least I’ll be able to test the broken stop mechanism more quickly on these short tapes, and save money if I break any more.

Maybe a decade ago, there was a reel to reel taoe deck at a garage sale. Something like $20, and it was decent (not 1960 consumer, not language lab). And I paused, thinking about how much I would have liked that decades before. And I realized I had no use for it.

Needless to say, I also left the 8track recorder sitting next to it. At least that was something that hadn’t been common (I said “recorder”)

I do have a couple of portable CD players that can play MP3s, from that transition period before all electronic MP3 players took over. And a couple of minidisc players.

FYI – there is no “must of”, what you want to use is “must have” or “must’ve”. Would of, should of, could of, etc. are all equally incorrect.

The second must of your sentence is superfluous, I think….

Or, more correctly, ‘The second “must” of your sentence is superfluous, I think…’ (This reverses the usual way of nesting qiotation marks.)

Pedant fight!

I guess the point most of the previous respondents comment upon is the plethora of old vintage junk,,,, uh I mean treasures,,,, and oh yes Grammer and spelling too …

Well, I for one am actually intrigued by your hack. Not so much for moving pictures type stuff , but the whole concept of repurposing photomechanical imaging devices in general.

In another lifetime ago , I worked professionally in lithographics as a dot mechanic. I was on the very forefront of electronic imaging and the digital revolution. I remember a day when Photoshop was not a household word and Adobe was a startup that was struggling to get a foot in the door somewhere.

I look back at much of the photo mechanical hardware and optical devices with much reverence. Much of it scrapped and as long gone or more so than the old Linotype machines. Ughhh !

I digress,,,

Fast forward from my imaging career up to about the time we started seeing the camera phone… I started noticing on the online auction sites all kinds of pro level expensive high end film cameras selling for a pittance.

I jumped into a rabbit hole and went on a bidding spree that found me with a bunch of Nikon and Canon 35mm SLR gear.

What was I thinking? More stuff I hoarded . Albiet very nice quality high end obsolete stuff.

Needless to say that I have always put in the back of my mind that there should be some way to repurpose some of this gear. Much of it with much finer optics and heavier duty mechanics then much of the current crop of digital slr offerings. I often wondered about some type of ccd array inside of a spoofed 35mm film cartridge. There have been digital backs built for some cameras , usually the larger format cameras. But nothing for a 35mm. You would think as popular a camera the Nikon F1 was for photo journalists and as many probably hiding in attics , storerooms and such places being hoarded, that there would be a way to repurpose or digitize these things!

I like the idea of the pi camera inside your Fuji 8mm film camera.

Someday I will do something with that gear!

More nostalgia,,,

I have an old CanonA4/Kodak DCS digital conversion camera system that utilized PCMCIA card storage and was a whooping 3 megapixels .

My work had one of these when it came out. I remember the service contract was 100k to renew for one year!!!! The Associated Press was pushing these things with their Leaf systems.

I bought mine for 24.00 dollars almost fifteen years ago!

There have been a couple of attempts at digital 35mm “film”. Some hard to work with issues are different camera brands, and models within brands, have different distances from center of film can to center of lens. The one that was almost a success worked with that by pre-adjusting their sensor position for a few models most commonly used in professional photography. That’s the main thing that sunk the company. They couldn’t support such a wide range of variability in camera design.

Then there’s how little thickness there is between the edges the film moves across behind the shutter and the plate which pushes the film forward and keeps it flat. Difficult to make something thin enough to squeeze into that space while making it strong enough to be handled.

After reading up on that digital film failure I came up with an idea for how to make the position of the sensor a one time user adjustable feature. That would mean the camera owner or a camera technician would have to do the last step of assembly. Or it may be possible to make the adjustment changeable to use the device with different cameras.

It should be far easier to make a digital 126 or 110 cartridge. There were a few models of 126 SLR cameras, among the best was made by Kodak and it was compatible with their Retina 35mm lenses, though some features on some lenses weren’t supported. For 110 SLR there were only two models. One was quite conventional in design while the other kind of looked like an ancestor to Apple’s QuickTake digital camera.

Another film camera with the potential to have a digital cartridge is the Kodak Disc line. A digital sensor exactly the size of Disc film’s minuscule pieces of film should be easy to find. Fill the rest of the cartridge with the electronics, a battery, and sensors to work with the camera controls.

Then there are the Polaroid instant cameras. How about a cartridge with a sliding button on the front that connects to a mechanism to lift lenses and mirrors up inside the camera to focus incoming light onto a small image sensor. By sliding the button back, all that collapses so the digital cartridge can be removed. It would have to block light from hitting the angled mirror in the back of the camera, which spreads the incoming light across the large piece of instant film.

Many 35mm cameras have removable backs. No need to install the sensor in the film gap in front of the pressure plate. Just create a new back with the sensor in the location of the film plane.

Isn’t there an existing product that already does that? The prototype used an RPi, but eventually moved on to their own hardware using a 16MP sensor.

Both Nikon and Olympus made 35mm backs with larger magazines for shooting with a motor drive. For larger format cameras there was also a Polaroid back. Commercial and fashion photographers used that a lot for checking framing. I can’t remember how the backs mounted, but I nearly bought one for a 35mm Olympus and it had a sliding shutter operated by a button underneath that covered the film aperture so you could take it off. I think it worked in conjunction with the lock mechanism.

You remind me of the Hasselblads with their interchangeable backs and sliding protective film covers.

The real problem with most digital backs for film SLR cameras (with at least an APS-c sized sensor) is that the thickness/bulk of them tends to make the viewfinder either difficult or basically impossible to get your eye up to.

A good example of this is Leica’s “Digital Module R” for their R8 SLR camera was so notorious for rendering the viewfinder basically useless (you’d have to embedd the top edge of its preview screen quite uncomfortably into your cheekbone to even try looking through it) that it seems to have been scrubbed from their history, it was that embarassing.

There was a crowd-funded project a few years ago, which was basically a frosted screen, mirror and raspi camera in a printed enclosure, but this apparently had awfull image quality and looked even bulkier than Leica’s DMR.

It’ a problem that on the surface seems like a “slam dunk”, but really turns out to be totally impractical.

Oh, my. I posted too soon. Sorry!

The old lenses will be excellent, and will work fine on a DSLR. Get a canon DSLR, they’ve got the largest lens mount so can mount almost any lens with a cheap non-optical shim adaptor. My old Contax-Yashica Zeiss lenses work fine (manual focus, but AF-confirm works, or can focus extremely accurately in line view)

The old bodies, probably not very useful unfortunately, unless you want to run 35mm though then, which is still a fun hobby.

I’m almost certain that there was a digital retrofit for 35 mm film cameras, but it apparently was made before the technology of the time was developed enough.

Now that we can sell (expensively) flexible high–res. displays for smartphones, shouldn’t it be possible to make thin sensors that bend before breaking? (The Casio Film Card calculator had the dimensions, afaik even the thickness, of a credit/debit card.)

I still have a Kodak DC 4800; it has a 16 sec. max exposure time; requires 32 sec. per shot, first 16 to image any bad pixels.

I recall seeing a digital back for Nikon 35mm F series cameras. I thought that it was a Nikon product for sports and journalism. It is possible that it was a 3rd party accessory.

As I remember, it mounted in place of the stock back (like a 250 {or 500?) shot film magazine did. The whole thing bolted to the camera bottom like a motor drive would. The batteries were inside the bottom housing.

I think it was made for Sports Illustrated and National Geographic level photographers mostly.

> both versions had a better picture quality that Standard 8.

than

> I’ve had a move camera on my desk,

movie

Good luck with the Pi camera conversion!

Neat use for it Jenny. Actually using it for shooting film seems like it’d be a needlessly expensive hobby; hacking it to digital’s the way to go!

Interesting. You know considering the age and construction of standard 8 that someone in the 50’s would have come up with a home 3D camera, does anyone know if anyone ever did?

In the 1950s Bolex produced a C-mount stereo adapter for their H16 16mm camera. The system also included a matching projector lens with polarised lenses.

So it could shot 3D? Sounds cool.

Why not have the Pi camera behind the mechanical shutter, and have it trigger the Pi to snap a frame when open?

That way a micro-randomness (for want of a better term) could be introduced into the frame rate instead of a perfect digital-timed frame rate.

And put the camera on a solenoid mount (say from a $2 quartz clock movement) zapped with random strength current pulses to add in that slightly jerky motion.

There’s a lot of fun in using these old cine cameras as they were intended. Although Single 8 film isn’t available, there are some options for Standard 8 film and new Super 8 is available from Kodak. 16mm film is also available from Kodak and Orwo. Expired unused film is also an option.

It’s eyewateringly expensive if you buy new film and get it processed and scanned professionally.

But learn to develop it yourself, and using old expired film can keep the costs down. It’s great getting recognisable images from an old roll of Kodachrome that expired in the 1970s developed as a black and white negative in Caffenol. Shot with a 1950s wind up camera. It’s a challenge to get decent results, but sometimes the failures are interesting in their own right.

There’s loads of scope for DIY hacks – time lapse adapters, film drying racks, solutions for scanning the film.

Using cine film in the 2020s is perfectly anachronistic and masochistic – so much easier to video with your phone -but it’s fun and particularly rewarding when things come together and you get some good or interesting results.

The sad thing is that nobody ever introduced a motion-picture-film adapter for any of the consumer film scanners. Baffling and idiotic.

Describes “Super 8”, “Standard 8”, “Single 8”, shows diagram of “Super 8”, “8mm”, “Double 8″… not super clear!

Maybe “Double 8” was 16 mm stock, run twice, then slit after processing?

“what must of been real objects of desire”

Really, “must of?” What’s that supposed to mean?

It’s a dialectical form of “must have”.

No. It’s the illiterate way.

No, it isn’t.

I think you meant “dialectal”, if there is such a word. (Try “colloquial”.)

“[…]shed some light on what must of been real objects of desire”

Ugh. Hate to be that guy but “must’ve” (what you were aiming for) is a contraction of “must have”. No such syntax as “must of”.

Edit: I should really read the comments before posting.

(Glad I’m not the only one that had a gut reaction to that…0

Nice idea! The form factor looks appealing, or at least something we don’t see much of these days. I also like your rule for impulse buys, I think I’ll have to borrow that one myself.

Normally I would again decry the gutting of a piece of classic kit just so a Pi could be stuffed inside, but I won’t bother this time. I’ll just look at my collection of classic cameras, including several wind-up 8mm cine cameras, and offer my condolences for the loss of their brethren.

Hi Jenny, I’m really interested in this single 8 reusable cartridge, and maybe develop into a 200 ft magazine for these cine cameras. To date only kodak produced such an item, but for super 8 cameras, plus this had sound stripe on it for direct sound recording , sadly long gone, but the cameras to take such a cartridge still exist, but not for single 8. I have another project i would like to discuss with you, please contact me on my email. Thank you.