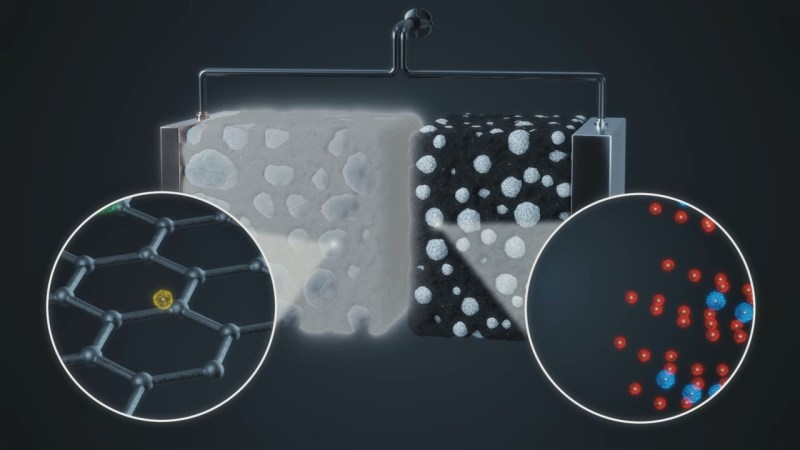

There’s a lot of magic in Lithium-ion batteries that we typically take for granted and don’t dig deeper into. Why is the typical full charge voltage 4.2 V and not the more convenient 5 V, why is CC/CV charging needed, and what’s up with all the fires? [The Limiting Factor] released a video that explains the low-level workings of Lithium-ion batteries in a very accessible way – specifically going into ion and electron ion exchange happening between the anode and the cathode, during both the charge and the discharge cycle. The video’s great illustrative power comes from an impressively sized investment of animation, script-writing and narration work – [The Limiting Factor] describes the effort as “16 months of animation design”, and this is no typical “whiteboard sketch” explainer video.

This is 16 minutes of pay-full-attention learning material that will have you glued to your screen, and the only reason it doesn’t explain every single thing about Lithium-ion batteries is because it’s that extensive of a topic, it would require a video series when done in a professional format like this. Instead, this is an excellent intro to help you build a core of solid understanding when it comes to Li-ion battery internals, elaborating on everything that’s relevant to the level being explored – be it the SEI layer and the organic additives, or the nitty-gritty of the ion and electron exchange specifics. We can’t help but hope that more videos like this one are coming soon (or as soon as they realistically can), expanding our understanding of all the other levels of a Li-ion battery cell.

Last video from [The Limiting Factor] was an 1-hour banger breaking down all the decisions made in a Tesla Battery Day presentation in similarly impressive level of detail, and we appreciate them making a general-purpose insight video – lately, it’s become clear we need to go more in-depth on such topics. This year, we’ve covered a great comparison between supercapacitors and batteries and suitable applications for each one of those, as well as explained the automakers’ reluctance to make their own battery cells. In 2020, we did a breakdown of alternate battery chemistries that aim to replace Li-ion in some of its important applications, so if this topic catches your attention, check those articles out, too!

Thanks to [Kelvin Green] for the tip!

Excellent, good post – timely also as locals I meet often at cafes, curious where we are going with Li Ion and solid state advances too,

Thanks

It was an interesting video, I am thankful for effort in making it.

Nope.

Yup. “Conduct” does not mean that the electrons MOVE at near the speed of light. Just as air conducts sound at hundreds of km per hour by transferring momentum from one molecule to the next without the molecules having any net motion, electrons conduct electricity without themselves moving an appreciable amount.

He explained how electrons do not _move_ at near the speed of light, but _conducts_ at near the speed of light, in the very same video you just watched, at 13:03.

What a useful and well thought out comment that really digs into the science of why you disagree with the content of the video. Truly breathtaking, I am awed by the eloquence with which you blew away the clearly flawed logic of this apparently amateur video. I am deeply honored to have seen your comment, and eagerly await your much better and more accurate video on the topic.

> not the more convenient 5 V

Thankfully the charging voltage is not 5V. The USB spec didn’t spec the voltage as 5V +10%/-0%. The loose *unregulated* voltage specs is just high enough to be implemented by an linear charger.

I have seen very dangerous implementation for cheapo made in China product using a single diode to drop from USB. The nasty part is that USB voltage can be higher than 5V and diode drop isn’t exactly 0.8V either – very temperature and current dependent. I bought properly designed and easy to use Li-ion charger chip for $0.05 from Aliexpress, so cost isn’t an excuse.

It is the battery chemistry that dictates the charging voltage. It is just high enough to maximize the battery capacity, but low enough to still have a usable lifetime and not dangerous or damaging to the battery.