When NASA astronauts aboard the International Space Station have to clamber around on the outside of the orbiting facility for maintenance or repairs, they don a spacesuit known as the Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU). Essentially a small self-contained spacecraft in its own right, the bulky garment was introduced in 1981 to allow Space Shuttle crews to exit the Orbiter and work in the craft’s cavernous cargo bay. While the suits did get a minor upgrade in the late 90s, they remain largely the product of 1970s technology.

Not only are the existing EMUs outdated, but they were only designed to be use in space — not on the surface. With NASA’s eyes on the Moon, and eventually Mars, it was no secret that the agency would need to outfit their astronauts with upgraded and modernized suits before moving beyond the ISS. As such, development of what would eventually be the Exploration Extravehicular Mobility Unit (xEMU) dates back to at least 2005 when it was part of the ultimately canceled Constellation program.

Unfortunately, after more than a decade of development and reportedly $420 million in development costs, the xEMU still isn’t ready. With a crewed landing on the Moon still tentatively scheduled for 2025, NASA has decided to let their commercial partners take a swing at the problem, and has recently awarded contracts to two companies for a spacesuit that can both work on the Moon and replace the aging EMU for orbital use on the ISS.

As part of the Exploration Extravehicular Activity Services (xEVAS) contract, both companies will be given the data collected during the development of the xEMU, though they are expected to create new designs rather than a copy of what NASA’s already been working on. Inspired by the success of the Commercial Crew program that gave birth to SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, the contract also stipulates that the companies will retain complete ownership and control over the spacesuits developed during the program. In fact, NASA is even encouraging the companies to seek out additional commercial customers for the finished suits in hopes a competitive market will help drive down costs.

There’s no denying that NASA’s partnerships with commercial providers has paid off for cargo and crew, so it stands to reason that they’d go back to the well for their next-generation spacesuit needs. There’s also plenty of incentive for the companies to deliver a viable product, as the contact has a potential maximum value of $3.5 billion. But with 2025 quickly approaching, and the contact requiring a orbital shakedown test before the suits are sent to the Moon, the big question is whether or not there’s still enough time for either company to make it across the finish line.

The Competitors

In the June 1st announcement, NASA revealed it had awarded contracts to Axiom Space and Collins Aerospace for a next-generation spacesuit that can serve crews on the International Space Station through to its tentative retirement in 2030 as well as support exploration of the Moon as part of the Artemis program. While the announcement mentioned an aspirational goal of eventually using some variant of the suit on a crewed mission to Mars, it’s not a specific requirement of the contract.

Those following recent space developments will likely recognize the name Axiom. The company seeks to develop their own private successor to the ISS that will be built as an extension of the orbiting laboratory until such time that it’s ready to be disconnected and operate as a free-flying station. As part of their preparations, Axiom recently conducted a privately funded mission to the ISS, during which several experiments relating to the design and development of future space station hardware were conducted.

During a press briefing about the announcement, Axiom President & CEO Michael T. Suffredini revealed his company had already been working on their own spacesuit design before they were selected for the xEVAS contract, which makes sense given their goal of eventually operating their space station free from NASA’s bureaucracy. The fact that Axiom will be able to keep the design of the suit even though its development will be funded by the space agency is also a huge boon for the company, and likely one of the reasons they agreed to the arrangement in the first place.

While Axiom Space is the definition of a “New Space” company, Collins Aerospace is anything but. A subsidiary of Raytheon Technologies, they designed the Apollo lunar spacesuits and are the prime contractor of the current EMUs. To say they have some experience in the spacesuit game would be something of an understatement.

Pitting an agile commercial space startup against an entrenched aerospace company that literally wrote the book on NASA’s spacesuits isn’t unlike the rivalry between SpaceX and Boeing to see which entity could be the first to design and build their own crew-rated spacecraft. The “New Space” competitor came away with a resounding win in that round, but it’s far too early to predict anything this time around.

The SpaceX Contingency

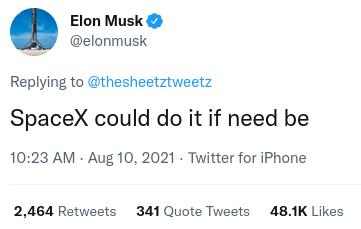

Some might be surprised that SpaceX wasn’t awarded a contract for the xEVAS program, given that the company already designed their own superhero-inspired suits for use aboard their Crew Dragon spacecraft. In 2021, Elon Musk even Tweeted that his company would take on the challenge of building a Moon-compatible spacesuit if that’s what it would take to make sure NASA stuck to its 2025 lunar landing deadline.

But realistically, NASA has already put most of the Artemis program on SpaceX’s shoulders. From awarding the company key roles in the construction and resupply of the Lunar Gateway Station to selecting Starship as the lander that will bring crews to the lunar surface, it’s no exaggeration to say that America’s lunar ambitions are almost entirely reliant on the Hawthorne, California company. For NASA to establish a long-term presence on the Moon, the Artemis program needs to maintain some level of diversity. Putting literally every step of the program into the hands of one company is simply too risky, even if the company has a track record of outperforming the competition.

But realistically, NASA has already put most of the Artemis program on SpaceX’s shoulders. From awarding the company key roles in the construction and resupply of the Lunar Gateway Station to selecting Starship as the lander that will bring crews to the lunar surface, it’s no exaggeration to say that America’s lunar ambitions are almost entirely reliant on the Hawthorne, California company. For NASA to establish a long-term presence on the Moon, the Artemis program needs to maintain some level of diversity. Putting literally every step of the program into the hands of one company is simply too risky, even if the company has a track record of outperforming the competition.

That said, SpaceX doesn’t have to wait on an invitation from NASA to develop a new spacesuit. In February, the company announced they would demonstrate a modified version of the Crew Dragon pressure suit that would allow conducting an extravehicular activity (EVA) from the capsule on the private Polaris Dawn mission currently scheduled for the end of 2022. So whether or not the company was officially tasked with coming up with a backup plan for putting boots on the Moon, it looks like there’s a good chance they’re working on it.

I think Duluth Trading Company should be given a go at it.

B^)

Yes atleast then it would be made in the usa

Make them like the Major Matt Mason moon suit? It was right out of the Time Life book about Space, so it originated at NASA.

A rigid structure with hands.

They are making deep sea diving suits that are rigid, really like tiny submarines. Build spacesuits along those lines.

The first problem is the weight: you have to put that into orbit first, and those rigid suits are VERY heavy.

The second problem is maintenance: I’m pretty sure that they require A LOT of it.

And I’m pretty sure that there are a lot more problems.

You’ll know it’s really a thing when you see your local scumbags posing around in Nike space pants.

“…to selecting Starship as the lander that will bring crews to the lunar surface…”

Didn’t I read that NASA now opened up the lander competition to several other companies? So Starship has not yet cinched the lander role.

Starship has got the contract for the first two demo flights (one uncrewed) a more than year ago. It’s done deal. Closed. Even the lizard from Amazon tried to sue and lost hard with appeals denied. And that is very *old* news.

What you may have read was about followup contracts and cargo contracts.

(Otherwise we’ll have to take Mr “”I could buy Twitter. Joking, I’m not buying Twitter. Actually I could buy Twitter. I am buying Twitter for real now. I’m not buying Twitter” at his word.)

Maybe there is a warehouse full of Rev. Hammer’s parachute pants that could be used.

Mais maman, l’Empereur n’a pas de vêtements.

Non, l’Empereur n’a pas de l’argent.

Plenty of argent, not enough brains. 60s engineers would be crying at the incompetence.

…. seulement les torche-culs anciens qui se desintegrant.

Or something that makes more sense, my French is bad.

Using google translate; “only the old torches that are disintegrating” ?

OK; I somewhat get It, I think. More like the old engineers are dying off, not disintegrating.

Brooks Brothers or Men’s Warehouse?

Knowing government Saville Row not Hong Kong bespoke.

“I like Skyway soap because it is as pure as the sky itself.”

[Just getting my contest entry in early for when they give the suits away as part of a contest.]

With apologies to R.A.H.

But those were surplus spacesuits. He had to put in a lot of work to make it viable again.

And don’t forget, first prize was a trip to the moon.

Hahaha. Still waiting for a good movie based on that. Let Greta Gerwig write and direct it.

Weren’t the mercury spacesuits made by maidenform, a bra company?

Afaik, the issue everyone had is stiffness when pressureized. A 10psi pressure differential makes stuff really inflexable.

It was either a DC (David Clark) or ILX (International Latex) one yes. There were also suits originally made for the Navy by BF Goodrich as well.

The mission you stated in the article for SpaceX at the end of the year for the first commercial EVA is not Inspiration 4, that mission has already flown. The SpaceX mission for the EVA is Polaris Dawn.

But civvy project code names usually give more clues about what is gonna happen, so I’m gonna go with it being the degreasing of a decommissioned surplus SLBM with dish soap.

Anyone working on side stepping the problem of suits entirely by making a telepresence drone? Immersive VR with a sensor laden shirt and gloves to track all limb movements seems very doable at this point, especially in zero G. Also reduces the need to launch humans at all for some types of maintenance.

We already have drones and we already know that they are unsuitable for interaction due to the speed of radio transmission.

Also the human body was not designed for work in zero g, and it was not designed to repair mechanical machinery, so your anthropomorphic drone will be much less effective than a purpose built machine that does not have to conform to human limitations.

> We already have drones and we already know that they are unsuitable for interaction due to the speed of radio transmission

Citation for these drones? Also, the claim that radio transmission speed is a problem is obviously false. The astronauts can be in the shuttle right next to the equipment and drones where speed is not an issue.

The problem being solved is with EVA specifically, so the drone just has to eliminate the need to EVA. Whether ground-based or space-based control is suitable can be decided on a case by case basis.

> your anthropomorphic drone will be much less effective than a purpose built machine that does not have to conform to human limitations.

It would also require considerably more training to use effectively. I also think you’re understating the flexibility of the human body for these tasks. Furthermore, the zero G remark is a total red herring, and while humans weren’t “designed” to repair machinery, we obviously designed the machinery to be repairable by humans.

I wonder if this has something to do with the fact NASA can’t figure out why their suits occasionally leak coolant internally.