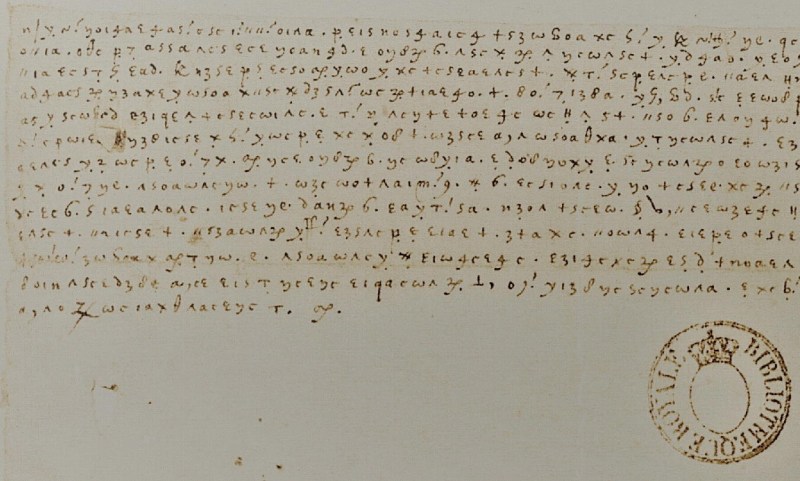

Communications by important people over the past thousands of years have been regularly encrypted, making the breaking of this encryption both an essential and also a fascinating historical field. One recent example of an important historical discovery by codebreakers are letters dating back to 1578 through 1584 by Mary Stuart, the Queen of Scots in the 16th century. While deemed lost for centuries, researchers came across them in a stash of encrypted letters that were kept at the Bibliothèque nationale de France’s (BnF). After decrypting these 57 letters, they realized what they had come across.

Even in digitized form, they could not simply be OCRed, leaving the researchers to manually transcribe each character into the software they used to assist with the decrypting. Only during the decrypting process, they began to realize that these were not Italian communications – matching the rest of the collection of which they were part – but in fact letters by Mary and her allies. Of the 57 letters, 54 are from Mary to Castelnau, the French ambassador in London at the time.

Supporting evidence for these decrypted letters being from Mary and Castelnau came from British archives, which had clear text versions of some of the encrypted letters, dated to the years when a mole within the French embassy was leaking translated texts to the English, as part of the usual political pastime during those centuries of getting onto thrones and making other people leave them. Mary’s attempt to become not only the Queen of Scots but also Queen of England came to a tragic end with her execution in 1587 after a politically motivated show trial.

The software the researchers used primarily is called CrypTool 2, which is an open-source project that provides cryptoanalysis and related functionality. The access to the documents themselves was enabled via the DECRYPT project, resources which taken together enables virtually anyone to undertake such historical sleuthing from the comfort of their own home.

(Thanks to [Stephen Walters] for the tip)

these letters also had elaborate security locks in the form

of a kind of oragami folded paper envelope that could not be opened and refolded,this was a oft used device of the times,and the recent find of an official lost mail stash from those time yielded a few unopened examples that were then scanned to reveal how they were done

Usually there was no envelope; the letter was folded on itself and sealed with a wax stamp. Attempting to re-seal the letter would leave tell-tale signs even if you had the same sealing stamp.

You’re both right. The letters were folded and sealed with wax without an envelope, but the folding in this case was an elaborate technique called “letter locking” which was virtually impossible to open without tearing the paper.

Now I am very much hoping that the next Hackerday article someone writes is gonna be in one of these code formats so that us readers can have fun trying to decipher it. First one to solve it gets a $10 Digikey coupon (from Digikey, not me)

Wow amazing find after all these centries. Unicode has some catching up to do!

Makes you wonder, how would you make a manual Enigma machine? The point of it was to have three to five wheels which would turn with every key stroke to scramble the letter, so you had to know the starting positions of the wheels and how much each of them turns to decipher the message – but it was based on electro-mechanical switches routing current between different contacts.

What if there was a 16th century version of that. How would it work?

A code wheel and Vigenère cipher is what would be closest. First described in 1553 it’s simpler than the system used by Mary and more secure, provided your key is long enough. The problem is that remembering and sharing a long key securely is kind of a challenge.

The Vigenère system wasn’t officially broken until the mid 19th century so in theory would have been secure enough, but sadly for Mary the compromise and turning of her couriers and the mole in the embassy mean that her key would probably get compromised at some point leading to the same result.

The Germans used a code book with a different key assigned for each day, then used that key to send the actual encryption key. That way they could always pick a new key at random for each message. The problem was, they always sent the key twice for some reason, which made it easier to figure out without the codebook.

I remember reading about this cypher in Simon Singh’s “The Code Book” back in 2000, so it was cracked long ago. In fact, it had been cracked by Queen Elizabeth’s agent Walsingham back at the time Mary was writing them. Part of the evidence against Mary was generated when Walsingham added to an actual letter from Mary a forged paragraph using the same code asking the conspirators to reveal their own names! A classic Man-in-the-Middle attack.

Copy, I asked myself, was is a mole or did. the English gain the content by deciphering it as Simon Sing describes it in his fascinating book “The code book” (from my point of view a must read!)

Cheers

Georg