The History Guy on YouTube has posted an interesting video on the history of the supercomputer, with a specific focus on their use by NASA for the implementation of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models of aeronautical assemblies.

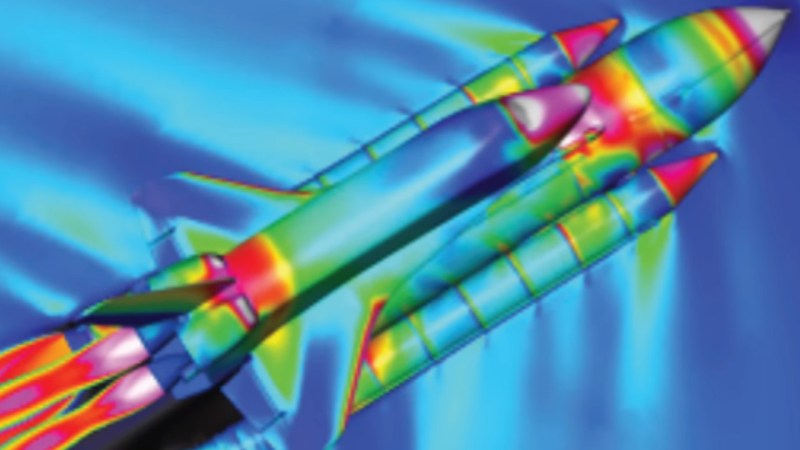

The aero designers of the day were quickly finding out the limitations of the wind tunnel testing approach, especially for so-called transonic flow conditions. This occurs when an object moving through a fluid (like air can be modeled) produces regions of supersonic flow mixed in with subsonic flow and makes for additional drag scenarios. This severely impacts aircraft performance. Not accounting for these effects is not an option, hence the great industry interest in CFD modeling. But the equations for which (usually based around the Navier-Stokes system) are non-linear, and extremely computationally intensive.

Obviously, a certain Mr. Cray is a prominent player in this story, who, as the story goes, exhausted the financial tolerance of his employer, CDC, and subsequently formed Cray Research Inc, and the rest is (an interesting) history. Many Cray machines were instrumental in the development of the space program, and now adorn computing museums the world over. You simply haven’t lived until you’ve sipped your weak lemon drink whilst sitting on the ‘bench’ around an early Cray machine.

Obviously, a certain Mr. Cray is a prominent player in this story, who, as the story goes, exhausted the financial tolerance of his employer, CDC, and subsequently formed Cray Research Inc, and the rest is (an interesting) history. Many Cray machines were instrumental in the development of the space program, and now adorn computing museums the world over. You simply haven’t lived until you’ve sipped your weak lemon drink whilst sitting on the ‘bench’ around an early Cray machine.

You see, supercomputers are a different beast from those machines mere mortals have access to, or at least the earlier ones were. The focus is on pure performance, ideally for floating-point computation, with cost far less of a concern, than getting to the next computational milestone. The Cray-1 for example, is a 64-bit machine capable of 80 MIPS scalar performance (whilst eating over 100 kW of juice), and some very limited parallel processing ability.

While this was immensely faster than anything else available at the time, the modern approach to supercomputing is less about fancy processor design and more about the massive use of parallelism of existing chips with lots of local fast storage mixed in. Every hacker out there should experience these old machines if they can, because the tricks they used and the lengths the designers went to get squeeze out every ounce of processing grunt, can be a real eye-opener.

Want to see what happens when you really push out the boat and use the whole wafer for parallel computation? Checkout the Cerberus. If your needs are somewhat less, but dabbling in parallel computing gets you all pumped, you could build a small array out of Pine64s. Finally, the story wouldn’t be complete without talking about the life and sad early demise of Seymour Cray.

If you ever get a chance to examine an old early-model Cray up close you should do it.

They’re an amazing example of “form follows function”

The racks of simple cards are pie-shaped, with the processing elements on the wide end and the interface elements on the narrow end, which brings them significantly closer than they would be if built as flat racks.

Those hundreds of boards are filled with low-integration ECL circuitry that gobbles amps like locusts gobble wheat fields, so the rack infrastructure itself provides massive power and cooling busses.

And what do we do about those giant power supplies and the huge IR drop on the way to the machine? We’ll just make them into seats and call it a style element.

Yes, the Crays were obviously thecomputational monsters of their day, but I think the coolest part is how much of what seems like just styling turns out to be real, functional design decisions.

Currently a mechanical designer at HPE in Chippewa Falls. My boss actually worked directly under Seymour and knew him well. Also work with others who worked at Cray while Seymour was around. Hear some crazy stories and love reading these things.

What we design now is pretty boring from an asthetical standpoint. Lots and lots of rectangles. I’m pretty jealous of the person who got to design the immersion cooling waterfall on the Cray 2.

But…I’m not jealous of whoever was in charge of cabling those things. It’s a challenge doing cabling now…back then…oof.

ECL based was my recollection too. I think they must of used all of Motorola’s output back then, not to mention ECL design personnel. ECL was a weird beast using analog differential transistor operation for speed (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emitter-coupled_logic), but not as weird as TI’s I2L (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integrated_injection_logic).

Agreed on seeing a Cray up close. Amazing.

Also amazing that less than $30 microcontroller now outperforms the Cray-1, at a millionth the cost and weight, and (almost) power consumption.

I wonder what ludicrously expensive thing these days will be had for lunch money in another 50 years. I hope I’m around to see it.

Hopefully rent but I don’t see that happening.

“You simply haven’t lived until you’ve sipped your weak lemon drink whilst sitting on the ‘bench’ around an early Cray machine.”

As someone who likes to buy orange soda for long “hacking” sessions, I may try this. Watered down soda or drink mix would probably be good for that.

Well, I know for a fact that you’re not allowed to sit on the Cray machine in the National Computing Museum at Bletchley, which is a shame. But you can get close enough to lick it if you were so inclined. Just saying. I think I’ve got some photos somewhere. Of the machine, not the licking part.

If you lve in the USA or elsewhere that self service soft drinks are common, I have found a 30:70 mix of cola and unsweetened iced tea to be quite good. A bit 9f sweetness from the cola, but the syrupy excess it cut by the tea. Both drinks are lightly caffeinated to keep you alert, but this mixture reduces the sugar by 70% compared to plain cola, without resorting to weird artifical sweeteners. If you are deiniing litres of the stuff per day, it is “less bad” than just chugging regular cola.

You may need to experiment with the ratio to find the right balance for you. I am not a dietician, this is not dietary advice etc :-)