Not every talk at the Chaos Communication Congress is about hacking computers. In this outstanding and educational talk, [Michael Büker] walks us through the history of our understanding of the planets.

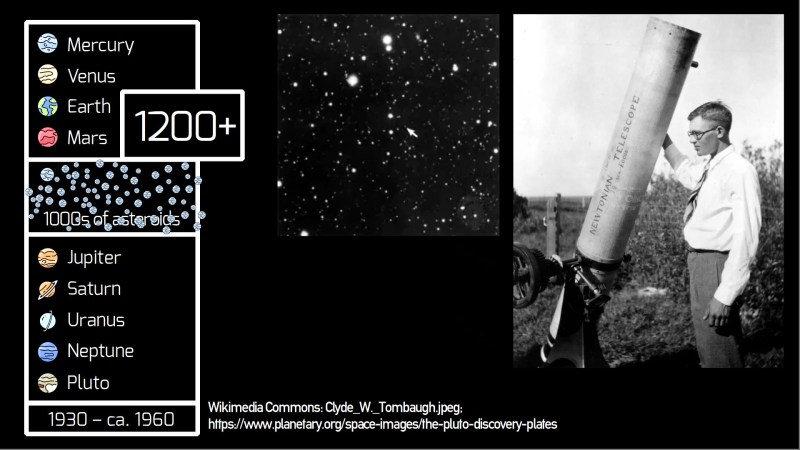

The question “What is a planet?” is probably more about the astronomers doing the looking than the celestial bodies that they’re looking for. In the earliest days, the Sun and the Moon were counted in. They got kicked out soon, but then when we started being able to see asteroids, Ceres, Vesta, and Juno made the list. But by counting all the asteroids, the number got up above 1,200, and it got all too crazy.

Viewed in this longer context, the previously modern idea of having nine planets, which came about in the 1960s and lasted only until 2006, was a blip on the screen. And if you are still a Pluto-is-a-planet holdout, like we were, [Michael]’s argument that counting all the Trans-Neptunian Objects would lead to madness is pretty convincing. It sure would make it harder to build an orrery.

His conclusion is simple and straightforward and has the ring of truth: the solar system is full of bodies, and some are large, and some are small. Some are in regular orbits, and some are not. Which we call “planets” and which we don’t is really about our perception of them and trying to fit this multiplicity into simple classification schemas. What’s in a name, anyway?

Pluto? I’m still waiting for them to readmit Vulcan…

I want them to fund a mission to flyby Chariklo, my favorite almost-planet. It has rings, and I’m pretty sure Space Ghost lives there.

The problem with the new “rules” for whether something is a planet is that you could take Jupiter, move it out from the sun a bit, and now it isn’t a planet anymore.

Also, being able to “clear it’s own or it” would also exclude Neptune… Pluto dips inside Neptune’s orbit, and hasn’t been cleared. Again, subjective.

“being able to “clear it’s own or it” would also exclude Neptune”

This is incorrect (as is the Jupiter comment). The “clear your neighborhood” requirement is intentionally vague, but it doesn’t mean the planet is the only object in the orbit. It means the planet’s gravity dominates the dynamics of its orbit (e.g. Jupiter and the Trojan asteroids, or Neptune/Pluto’s resonance).

“Intentionally vague” is the entire problem. It is tuning the rules to get an outcome one desires, rather than an actual rule.It comes from the thought that should be a small number of plants, and therefore we need some arbitrary rule to exclude things that would otherwise qualify.

It becomes a lot clearer when you read the history of how the vote was taken. Last day of a week long conference, after most members had already left. Less than 4% of the members voted. And I -think- that the vote was unannounced, but I can’t find a citation off hand.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/pluto-scientists-battle-planet-definition-1.4032382

I agree. The current rule seems to be a lame excuse. To me, it’s as if it was made to prevent further discoveries to match the old planet criteria.

There must be some fear about ending up with ~20 or more planets in the solar system. So Pluto had been sacrificed instead.

It really isn’t. It’s more about formation and dynamics.

Pluto really isn’t a characteristic body in our Solar System: it only exists because of a narrow stability window between the outer planets. It doesn’t really affect the dynamics of the Solar System as a whole – take it away, and nothing really changes.

That’s what they’re trying to capture in the definition: the ‘major planets’ are the ones you need to include to determine the overall dynamics of the Solar System on long timescales with good accuracy, because they’re the ones that dominate the gravity.

It’s intentionally vague because we only have one solar system with detailed measurements. The range of cutoffs you could use for size is gigantic.

There are alternate definitions based on just size/orbit/stellar mass parameters that a few scientists found that also map very well to most of those, so you could translate it into a specific parameter range if you wanted.

Also the “voting percentage” bit is silly, the majority of the IAU membership is really just there for the label.

there are a number of formulae to determine what “cleared the neiborhood” means. though i don’t think the iau have definitively picked one yet. frankly i find this definition to be fuzzy and subject to arbitrary thresholding and depending on estimates of how much stuff is in a planets orbit (because its never zero).

in the case of neptune even though the orbits appear to cross from a top town projection they never come close enough at closest possible approach for one planet to influence the other significantly.

“frankly i find this definition to be fuzzy and subject to arbitrary thresholding”

Yeah. That’s the point. The Solar System itself doesn’t give you enough information to know of a good place to put the distinction, and planet formation simulations and observations don’t quite help you enough yet. The definition is a “guide” that lets formal definitions evolve over time, but keeping the same spirit.

The “clear the neighborhood” bit in astronomer-speak can be reformulated into a combination cut on the planet’s mass, orbital distance, and star size. The real fuzziness is only in how clear does it have to be and how long does it have to take. For instance, Margot ( https://arxiv.org/abs/1507.06300 ) is frequently used, and is a good example of concrete boundaries derived to satisfy the intention of the definition.

You can see in that paper exactly how far objects like Ceres, Eris, and Pluto are: they’re at least 1000x away from the least planet-like planet (which is Mars). That’s why it’s fuzzy – there’s a *massive* gap that you could put the cut line anywhere in.

Now I want to see an orrery made with the larger asteroids and Trans Neptunian Objects included…

You are thethe catalyst of your destiny.

Make it happen.

B^)

I want to see it too! Go go go! :)

753…754…755…756….

I think Pluto should be grandfathered back in.

All these human convenience categories have nothing to do with reality. How inconvenient can it be for Pluto to be an honorary planet?

Pluto is a planet, and will remain so until I am gone… which will be neither noted nor cared about by anyone in the scientific community. Nor by anyone else, really. Ok, but dammit, Pluto is a planet.

I agree!

Pluto’s got 5 moons. It’s a planet.

Is round, has moons seems like pretty good rule to me too. But then when you start looking at the other trans-neptunian objects, we don’t yet know how many will fit those criteria. I bet there are others out there that we have yet to discover.

Was pointed out by others @ Congress when talking about this: a Pluto year is 200+ earth years long. It was only a planet for ~50. Pluto had a good summer.

A planet is a sub-stellar mass body that has never undergone nuclear fusion and that has sufficient self-gravitation to assume a spheroidal shape adequately described by a triaxial ellipsoid regardless of its orbital parameters. Simple. Sure, that means there may be hundreds of planets in the solar system, but why should the number of something be a reason for rejecting a reasonable definition?

Hundreds or thousands.

Go to the end of the talk — what you’re defining is a “dwarf planet”. He says that there are so many of them being discovered nowadays that the IAU won’t even pick up the phone.

No, size is irrelevant except to say that it has to be less massive than a star. There is no distinction between “planet” and “dwarf planet” in the definition I shared. Yes, that means Earth’s moon would be properly classed as a planet, and that Mars’s moons would not be.

I agree. To be fair, earth/moons relationship is kind of that of a dual planet system.

Well… somewhat. Not from a “dynamics of the Solar System” standpoint – the Moon’s mass is too low to really make a difference as to whether or not you treat “Earth+Moon” as a single object or as two separate. And that’s really where the “planet” definition is coming in.

But yes in the “dynamics of the Earth itself” standpoint: because the Moon is relatively dicey in terms of how far out it is (it orbits at half the Hill radius – the distance at which the Earth is the dominant gravitational force), if you want to find out what happens to the *Earth*, you need to include the Moon (because the Moon frequently collides with the Earth if you perturb it).

Essentially, the Moon (as an independent body) doesn’t really matter to the Solar System so long as everything’s relatively stable, but as soon as things start having strong interactions it matters a lot more.

(The fact that it’s a borderline between being a “dual planet” isn’t surprising because true “dual planets” in the inner solar system are almost certainly unstable.)

“Sure, that means there may be hundreds of planets in the solar system, but why should the number of something be a reason for rejecting a reasonable definition?”

Because you don’t need hundreds of objects to simulate the dynamics of the solar system to good precision for a long time. You need eight. Adding the dynamics of Pluto, Ceres, or Eris does virtually nothing compared to just slightly adjusting a measurement of one of the major planets’ orbital parameters.

I despair

A thread about planets, and no-one, none has asked if they can see Uranus?

Thanks, but no, I’m not in the mood right now to see Uranus.

We could just simplify it to anything with enough mass to become roughly spherical under it’s own gravity. We’d have hundreds of planets per solar system, but then the only exceptions would be rather clear-cut, such as moons (orbiting other planets), binary (trinary, etc.) planets (or moons very close to the same size as their planet), and rogue planets (not part of a solar system or very unclear which one they belong to).

“We could just simplify it to anything with enough mass to become roughly spherical under it’s own gravity.”

That’s a dwarf planet. A planet (no “dwarf”) adds the third distinction (clear the neighborhood) which kicked Pluto out of the class.

If you come up with basically *any* reasonable definition for ‘clear the neighborhood’ (which only requires you to choose a timescale to clear it over and a distance that has to be cleared, in terms of the Hill radius) and plot all Solar System objects on that graph, there is a *massive* gap between the eight planets and everything else. Massive. Factor of 1000.

And all of the 8 planets are actually pretty close together in that value. There’s less range (factor of ~740) between the biggest (Jupiter) and smallest (Mars) than there is between the masses of those planets (a factor of ~5800 between Jupiter and Mercury).

If you want to say “just drop the dwarf!” – fine, but the 8 planets *are still in a class of their own*. There’s nothing you can do to avoid that. They just are. You could change the current “dwarf planet” to “planet” and the current “planet” to “major planet” but then people are just saying “there are 8 major planets in the solar system.”

It’s not even the same as “inner planets” versus “outer planets” – even though all the inner planets are lower mass than the outer planets, both Earth and Venus have more dominance of their orbit than Uranus or Neptune.

Excluding Pluto (or Ceres, or Eris, or anything else) from the other 8 has nothing to do with an arbitrary definition. It’s astrophysics.