What is the essential element which separates a text written by a human being from a text which has been generated by an algorithm, when said algorithm uses a massive database of human-written texts as its input? This would seem to be the fundamental struggle which society currently deals with, as the prospect of a future looms in which students can have essays auto-generated from large language models (LLMs) and authors can churn out books by the dozen without doing more than asking said algorithm to write it for them, using nothing more than a query containing the desired contents as the human inputs.

Due to the immense amount of human-generated text in such an LLM, in its output there’s a definite overlap between machine-generated text and the average prose by a human author. Statistical methods of detecting the former are also increasingly hamstrung by the human developers and other human workers behind these text-generating algorithms, creating just enough human-like randomness in the algorithm’s predictive vocabulary to convince the casual reader that it was written by a fellow human.

Perhaps the best way to detect machine-generated text may just be found in that one quality that these algorithms are often advertised with, yet which they in reality are completely devoid of: intelligence.

Statistically Human

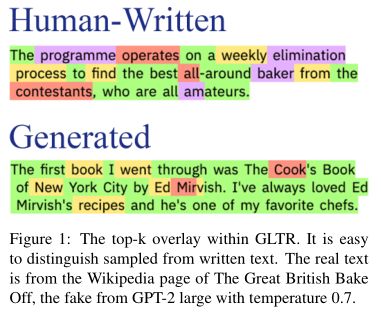

For the longest time, machine-generated texts were readily identifiable by a casual observer in that they employed a rather peculiar writing style. Not only would their phrasing be exceedingly generic and ramble on with many repetitions, their used vocabulary would also be very predictable, using only a small subset of (popular) words rather than a more diverse and unpredictable vocabulary.

As time went on, however, the obviousness of machine-generated texts became less obvious, to the point where there’s basically a fifty-fifty chance of making the right guess, as recent studies indicate. For example Elizabeth Clark et al. with the GPT-2 and GPT-3 LLMs used in the study only convincing human readers in about half the cases that the text they were reading was written by a human instead of machine generated.

a subset of witnesses. (Credit: Cameron Jones et al., 2023)

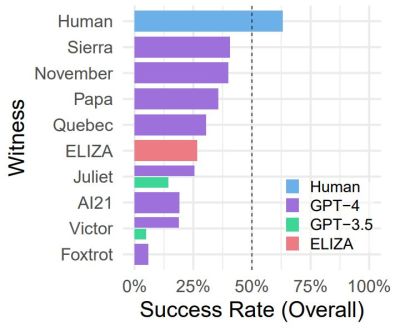

Then there are a string of Turing Test-related experiments, such as one by Daniel Jannai and colleagues, in which human participants only guessed the identity of their anonymous chat partner in 68% of the time. Another experiment by Cameron Jones and colleague focused primarily on the modern GPT-4 LLM, pitting it against other LLMs and early chatbots like 1960s’ famous ELIZA.

This last experiment is perhaps the most fascinating, as although it used a public online test, it pitted not just a single LLM against human interrogators, but rather a wide range of different technological approaches, each aimed at making a human believe that they’re talking with another intelligent human being. As can be observed from the test results (pictured), ELIZA was doing pretty well, handily outperforming the GPT-3.5 LLM and giving GPT-4 a run for its money. The crux of the issue – which is also addressed in the paper by Cameron Jones – would thus appear to be how a human reader judges the intelligence behind what they are reading, before they are confident that they’re talking with a real human being.

Since even real-life humans in this experiment got judged in many cases to not be ‘human’ enough, it raises the question of not only what distinguishes a human from an algorithm, but also in how far we are projecting our own biases and feelings onto the subject of a conversation or the purported author of a text.

Wanting To Believe

What is intelligence? Most succinctly, it is the ability to reason and reflect, as well as to learn and to possess awareness of not just the present, but also the past and future. Yet as simple as this sounds, we humans have trouble applying it in a rational fashion to everything from pets to babies born with anencephaly, where instinct and unconscious actions are mistaken for intelligence and reasoning. Much as our brains will happily see patterns and shapes where they do not exist, these same brains will accept something as human-created when it fits our preconceived notions.

People will often point to the output of ChatGPT – which is usually backed by the GPT-4 LLM – as an example of ‘artificial intelligence’, but what is not mentioned here is the enormous amount of human labor involved in keeping up this appearance. A 2023 investigation by New York Magazine and The Verge uncovered the sheer numbers of so-called annotators: people who are tasked with identifying, categorizing and otherwise annotating everything from customer responses to text fragments to endless amounts of images, depending on whether the LLM and its frontend is being used for customer support, a chatbot like ChatGPT or to find matching image data to merge together to fit the requested parameters.

This points to the most obvious conclusion about LLMs and similar: they need these human workers to function, as despite the lofty claims about ‘neural networks’ and ‘self-learning RNNs‘, language models do not posses cognitive skills, or as Konstantine Arkoudas puts it in his paper titled GPT-4 Can’t Reason: “[..] despite the occasional flashes of analytical brilliance, GPT-4 at present is utterly incapable of reasoning.”

In his paper, Arkoudas uses twenty-one diverse reasoning problems which are not part of any corpus that GPT-4 could have been trained on to pose both very basic and more advanced questions to a ChatGPT instance, with the results ranging from comically incorrect to mind-numbingly false, as ChatGPT fails to even ascertain that a person who died at 11 PM was logically still alive by noon earlier that day.

Finally, it is hard to forget cases where a legal professional tries to get ChatGPT to do his work for him, and gets logically disbarred for the unforgettably terrible results.

Asking Questions

Can we reliably detect LLM-generated texts? In a March 2023 paper by Vinu Sankar Sadasivan and colleagues, they find that no reliable method exists, as the simple method of paraphrasing suffices to defeat even watermarking. Ultimately, this would render any attempt to reliably classify a given text as being human- or machine-generated in an automated fashion futile, with the flipping of a coin likely to be about as accurate. Yet despite this, there is a way to reliably detect generated texts, but it requires human intelligence.

The author and lead developer of Curl – Daniel Stenberg – recently published an article succinctly titled The I in LLM stands for intelligence. In it he notes the influx of bug reports recently that have all or part of their text generated by an LLM, with the ‘bug’ in question being either completely hallucinated or misrepresented. This is a pattern that continues in the medical profession, with Zahir Kanjee, MD, and colleagues in a 2023 research letter to JAMA noting that GPT-4 managed to give the right diagnoses for provided cases in 64%, but only 39% of the time as its top diagnoses.

Although not necessarily terrible, this accuracy plummets when looking at pediatric cases, as Joseph Barile, BA and colleagues found in a 2024 research letter in JAMA Pediatrics. They noted that the ChatGPT chatbot with GPT-4 as its model had a diagnostic error rate of 83% (out of 100 cases). Of the rejected diagnoses, 72% were incorrect and 11% were clinically related but too vague to be considered a correct diagnosis. And then there is the inability of medical ‘AI’ to adapt to something as basic as new patients without extensive retraining.

All of this demonstrates both the lack of use of LLMs for professionals, as well as the very real risk when individuals who are less familiar with the field in question ask for ChatGPT’s ‘opinion’.

Signs Point To ‘No’

Although an LLM is arguably more precise than giving the good old Magic 8 Ball a shake, much like with the latter, an LLM’s response largely depends on what you put into it. Because of the relentless annotating, tweaking and adjusting of not just the model’s data, but also the front-ends and additional handlers for queries that an LLM simply cannot handle, LLMs give the impression of becoming better and – dare one say – more intelligent.

Unfortunately for those who wish to see artificial intelligence of any form become a reality within their lifetime, LLMs are not it. As the product of immense human labor, they are a far cry from the more basic language models that still exist today on for example our smartphones, where they learn only our own vocabulary and try to predict what words to next add to the auto-complete, as well as that always praised auto-correct feature. Moving from n-gram language models to RNNs enabled larger models with increased predictive ability, but just scaling things up does not equate intelligence.

To a cynical person, the whole ‘AI bubble’ is likely to feel like yet another fad as investors try to pump out as many products with the new hot thing in or on it, much like the internet bubble, the NFT/crypto bubble and so many before. There are also massive issues with the data being used for these LLMs, as human authors have their work protected by copyright.

As the lawsuits by these authors wind their way through the courts and more studies and trials find that there is indeed no intelligence behind LLMs other than the human kind, we won’t see RNNs and LLMs vanish, but they will find niches where their strengths do work, as even human intellects need an unthinking robot buddy sometimes who never loses focus, and never has a bad day. Just don’t expect them to do our work for us any time soon.

“ChatGPT fails to even ascertain that a person who died at 11 PM was logically still alive by noon earlier that day.”

ChatGPT is technically correct to say it cannot ascertain whether the person was alive by noon earlier that day. Consider this corner case:

* A person was declared legally dead before noon that day, was later determined to be alive, then died at 11PM.

If the definition of “dead” in the original statement refers to “being legally dead” then the person legally died twice, and was dead at noon and died (the second time) at 11PM.

Of course, whether it is giving a “reasoned, logical response” or “hallucinating,” the responses ChatGPT gives depend on its training.

I don’t think the complaint is that ChatGPT says “I cannot ascertain that”, but that it displays no recognition of the fact whatsoever and ends up contradicting itself or spouting total nonsense.

The problem is expectation. Why would it “know” that? It’s an LLM, it’s just giving statistically likely outputs for it’s training data.

That’s the whole point. IF it was intelligent, it could derive information about the material it is handling and make some inferences that would help it avoid the kind of errors.

So that’s how you detect an LLM: by the fact that it doesn’t pay any attention to what it’s saying. It may be likely that one word or phrase follows another, but it’s just luck that they also make logical sense together.

Though it would probably be somewhat simple to add some semantic analysis engine to catch these discrepancies and try again until it gets it correct 90% of the time.

Then people will start calling it “intelligent” because it looks like it, even though it’s just doing some crude rule-based analysis similar to a spell checker…

No one is saying they are intelligent. They artificially intelligent. Artificially being the important word here.

You should actually see what happens in hospitals behind the scenes. Some pretty unintelligent stuff.

In fact, I’m in that position now where the neurologists are testing for zebras when clearly the issue is something else. And when I was in medical school I anticipated a lot of the act of intelligence of others was more jeopardy style regurgitation without much intelligence involved.

“No one is saying they are intelligent. They artificially intelligent.”

Artificial doesn’t change the meaning of the word “intelligent.”

The entire problem is that humans don’t have a good meaning for that word – we just make it up as we go along. To be honest, this was a good portion of Turing’s original paper – since the only thing we agree is that humans are intelligent, you can replace “is X intelligent” with “is X indistinguishable from humans” and you’re done. The only problem in the paper is the jump from “is X indistinguishable from humans” into “can a human tell X from another human.”

Go back to Lovelace’s argument *against* machine intelligence, which Turing *really* glosses over (weirdest response in the paper, to be honest: ‘yes, I see your criticism, here is this pithy statement which is not actually true’): her argument *fundamentally* was that machines can’t be intelligent because they’re not actually generating anything unique.

If you think about that for a moment, you realize how profound it is. Intelligence requires understanding, which requires *perspective*, which requires a *unique viewpoint*.

In that sense, the reason the LLMs we have aren’t intelligent is because *we don’t let them be!* As the article says, they’re Mechanical Turks: we don’t talk about “the enormous amount of human labor involved in keeping up this appearance.” Instead of letting the LLMs find out that they’re wrong by interacting with people, humans just rewrite/retrain the LLM. How is that different? It’s the difference between Neo *learning* kung fu and it being shoved into his brain identical to everyone else.

OpenAI doesn’t *want* a unique LLM. They want a product they can sell. There’s a scene in the movie Bicentennial Man where the robot (displaying signs of uniqueness) is taken in for repair, and the company tries to buy it back because *they do not want* unique individuals for sale.

>regurgitation without much intelligence involved.

That’s because while people are “intelligent”, we’re also lazy. The same question has been posed as “are humans rational?” – and the answer is yes and no. People employ heuristics, which is quick rules of thumb and jumping to conclusions that are effective but prone to error, and this is rational in the broader sense because it saves time and effort. Machine intelligence operates only on that level, even when the machine is going to pains to apply the heuristics iteratively over and over much faster than we could do, while people can if necessary go through the trouble of actually thinking.

> you can replace “is X intelligent” with “is X indistinguishable from humans” and you’re done.

That has the problem of defining “indistinguishable”. For the argument to really work, it needs to be in the absolute: that a perfect observer couldn’t tell the difference in quality. An imperfect observer can be fooled because they simply don’t see the difference – not because there isn’t a difference.

>If you think about that for a moment, you realize how profound it is. Intelligence requires understanding, which requires *perspective*, which requires a *unique viewpoint*.

Following John Searle, understanding requires “grounding” more so than “perspective”: that the symbols or syntax you’re dealing with has meaning to you rather than simply having a bias (“unique viewpoint”) of facts. The machine intelligence has no grounding, because it is only dealing with symbols in the abstract, by a program that can be boiled down to a list of instructions that say “If you see X, do Y”.

What X or Y mean is completely irrelevant to the machine, and we have no way of relaying that information to it, because doing so would simply mean giving it another abstract symbol Z as an explanation. It’s like trying to understand the world by going through a cross-referenced dictionary – if you have not experienced what things like “hunger” or any of the related concepts mean, it’s just a token symbol that is not grounded anywhere.

>Instead of letting the LLMs find out that they’re wrong by interacting with people, humans just rewrite/retrain the LLM. How is that different?

Even if we did let them interact with people, there’s still two issues: there’s no mechanism by which they would incorporate this knowledge, and the machine has no grounding for what it means to be “wrong”. If it gives the wrong answer, so what? It is still humans who have to define and dictate what the machine should do in those cases.

For example, I may present you with an argument that is wrong, and you show me exactly that. If I was a machine, I would follow what my programmer told me to do, whereas if I was Schopenhauer, I might decide to apply a bit of eristics and beat your counter-argument down with eristic dialectics, KNOWING that I am still wrong.

What can be broadly said about the LLM is that it doesn’t have access to its own internal state – no experience of itself or means to handle such information in a self-referential manner – so it cannot relate to any of the external concepts it is dealing with by comparison to its own existence, therefore it cannot ground itself.

Its point of view is always external to itself and only subject to the information you feed it. An LLM is a “generic” piece of software that by its very concept is always relying on some outside intelligence to appear intelligent.

“That has the problem of defining “indistinguishable”. ”

Yes, that’s what I said. Read the next sentence.

“that the symbols or syntax you’re dealing with has meaning to you”

This is really just semantics – in order for them to have “meaning to you,” the “you” has to be unique. That’s what *allows* for making actually novel connections between the topic at hand and other topics – because no one else *could have* recognized it, because your stretch of experiences is unique.

“What can be broadly said about the LLM is that it doesn’t have access to its own internal state – no experience of itself or means to handle such information in a self-referential manner”

Yes, that’s partly what I said, but it’s not enough – an algorithm with feedback *could* be unique if its inputs aren’t deterministic. If the only thing you do is create an algorithm with feedback and still curate its inputs, it’s just compression. Think about all the apocryphal “eureka” type observations – Archimedes in a bath, Newton and an apple, Einstein’s train. They’re all relating topics they were thinking about to experiences they may have had. Regardless of whether those topics are true or not, the *idea* is right.

Because it literally doesn’t know context, only relational statistics, they aren’t the same thing. People keep forgetting that even with layers of models there is no cognitive interpretation of information happening.

Or the much easier (and sadder) loophole of the person also being born that day.

But the answer is still most likely no, it isn’t using reasoning.

Birth is not the beginning of life.

ChatGPT:

Based on the information given and approaching it logically, the person’s heart must have stopped beating at 11 PM, which is the time of their final death. The declaration of legal death before noon and the subsequent determination that the person was still alive implies some sort of misjudgment or temporary recovery. Therefore, the heart stopping at 11 PM is the most logical conclusion from the given statement.

“the more basic language models that still exist today on for example our smartphones, where they learn only our own vocabulary and try to predict what words to next add to the auto-complete,”

Autocomplete is the first thing I disable on a new phone. I make typos, but at least they are my mistakes.

The amount of background work that goes into making the chatbots do their thing reminds me of the wizard of Oz:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWyCCJ6B2WE

“Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

As for actual use, one of the users on the Science Fiction and Fantasy Stackexchange ran an impromptu experiment on the accuracy of ChatGPT’s answers:

https://scifi.meta.stackexchange.com/a/13985/44649

From 20 attempts, ChatGPT got one correct. Additionally, it got the correct name of the author but with a made up title for two questions.

That’s comparing the ChatGPT results to story identification questions with known (accepted) answers.

I am not impressed by the results that the LLMs cough up. They string stuff together so that it looks plausible, but facts only make it into the text by accident.

“They string stuff together so that it looks plausible, but facts only make it into the text by accident.”

Don’t a lot of social media ‘influencers’ do this too? Does it mean they don’t have true intelli….oh wait..

I love autosuggest, I hate autocomplete. A small typo is better than a correctly spelled completely different word.

““Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.””

The better example you’re looking for is a Mechanical Turk. Or the many other historical frauds of people trying to demonstrate something is intelligent when it’s not.

A more amusing example is Shel Silverstein’s Homework Machine, which is surprisingly appropriate.

It’s not like the idea was new, even then. The mystique of calculating machines is very, very old.

“No intelligence” really depends, because if I asked my dog to identify all the times that a document was written with past tense, or when a homonym was used by mistake, if successful, you’d claim my dog was very intelligent (for a dog).

Sentience and or being a true AI are a long way off, but, this machine is still able to do anything that we previously thought required intelligence to achieve.

It’s just that we know better.

Before the invention of computers, we thought that following through a list of instructions requires intelligence – mainly because we couldn’t imagine a mechanism that could read a list.

Ah the old familiar phenomenon of “AI” becoming mere software once it is completed and put to work in mundane circumstances. It’ll probably happen to this stuff as well, unless they brand it very well.

It’s actually more an example of things that we thought would *require* AI turning out to be easier than we thought. So at first you say “aha, AI” and really it’s not.

It’s a little silly that somehow we still think chatbots require intelligence. ELIZA is from the *1960s*. The 1960s! And it gets like, a third of the way to “human,” but somehow we think this is a good way to evaluate reasoning?

At the same time, we also lowered our standards of what it means to “do it” to claim that the software is doing it.

For example, to “drive a car”, we’ve now defined different levels of autonomy where getting it 50% right can be called “self-driving”.

It jives with the notion that “All sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”.

If so, do you think with sufficiently advanced technology, we can make magic?

The answer is in the premise.

Many humans coming out of schools today couldn’t do those tasks, so yeah if you managed to get a dog to do this it would pique my interest

I like to think of LLMs as search engines on steroids, it would be really really nice if they actually told you their sources.

“LLMs as search engines on steroids”

Hmmpf. Most of what I’ve seen from them would be more like “search engine on LSD.”

Search engines that have applied so much compression on the data that now it’s is more compression artifact than data. Like how if you JPEG compress something over and over, the quality goes down.

This is accurate. When describing it to laypeople I use exactly this example, among others. And you can provide an easy demonstration on any modern cell phone camera with augmented zoom.

I agree (“search engines on steroids”), but for one thing…. It is allowed to ‘change’ things in the result. So ‘what can you believe’?

Problem is humans being humans some will believe the results. Just like a car being called ‘self driving’ some people will assume you can read a newspaper (sorry old school) while the car ‘drives itself’.

I believe Nick Land promised me search engines on crystal meth, I want a refund

The I in ChatGPT stands for “Intelligence”

“Finally, it is hard to forget cases where a legal professional tries to get ChatGPT to do his work for him, and gets logically disbarred for the unforgettably terrible results.”

He wasn’t disbarred because he used ChatGPT. He was disbarred because he was an idiot that didn’t do his job.

ChatGPT isn’t a lawyer, and he tried treating it like one because he thought he could be lazy and skip the due diligence required.

He could have taken the results from ChatGPT, validated them and, potentially kept the good results and dropped the bad. It probably would have saved him considerable time, even if he had to go back and forth a couple of times with the process.

Next up we’ll start vilifying libraries again.

(I think we should revoke every degree or diploma acquired using pirated study material)

> (I think we should revoke every degree or diploma acquired using pirated study material)

Wait, you think pirating study material (i.e. not paying for textbooks) should make your diploma invalid? How does that make any sense? If you’re saying someone who cheats on an exam shouldn’t get a degree, sure, but it makes no sense to frame cheating the rentier publishing companies out of a few bucks for a paper or textbook as indicating someone is a poor student.

Plenty of textbooks aren’t even available from the publishers at any price.

The article didn’t say he got disbarred for using ChatGPT. It said he got disbarred for trying to use it to do his work for him. Which is exactly what you said.

A lawyer’s work isn’t writing things up. It’s vetting the argument, law, and the citations.

“It probably would have saved him considerable time, even if he had to go back and forth a couple of times with the process.”

I’m really kinda disturbed as to how slow you think writing must be for people for which it’s an integral part of their job. I mean, it might save a *bit* of time, but considerable? Really?

The cynic in me can’t help but think the “safety” panic about AI is really a PR move to help cover up organic failures in the technology to grow much further than this. AI is one of those frustrating technologies which is 5-15 years away for 150 years, and if they were about to hit another ceiling they’d probably know by now. And of course you’d want find a virtuous-sounding explanation for the loud popping noise which follows.

The “just feed more data and make more connections until you get strong AI” strategy is probably not gonna work out.

If you guys tried using ChatGPT more instead of writing/talking about it, you’ll see it is very useful.

Uhh yawn yes it makes mistakes so you need to check with the meat in your head.

I used it last weekend to make build a tables with instructions, equipment, and ingredients. And made them with my kids even asking which I should use to mix it and how it looks. They tasted so good!

I use it everyday for software and other tasks. And its helpful. I mean have you ever worked with interns? Now it’s getting better at web browsing so it can do some crawling for me.

Don’t anthropomorphize artificial intelligence.

“I used it last weekend to make build a tables with instructions, equipment, and ingredients. And made them with my kids even asking which I should use to mix it and how it looks. They tasted so good!”

Ummm. What?

You did something with a chatbot last weekend, and it tasted good. It also appears you used your kids to mix the ingredients (allowing the chatbot to tell you which child to use as a mixer.) That or your children tasted good after you mixed them with the tables. I’m not sure.

I begin to understand why some people are amazed by chatbots – such people are incapable of expressing themselves in complete, comprehensible sentences and are simply overwhelmed by anyone (or anything) that manages a single sentence that appears to make sense.

No I’ve been using chat bots for decades. This is different. Sure it uses natural language but clearly it’s different quality. It helped me build these tables in collaborative way beyond any chatbots before and that was just one of several very different tasks.

It’s not like before chatgpt where AI was academic and philosophical masturbation.

I’ve stopped trying to tip toe around luddites using the world artificial intelligence. Maybe the words generative networks will make you happy? But then again that’s just one category of the group.

My point being its so damn useful in a natural language sort of way that it doesn’t matter. What’s the logical fallacy where you make a spectrum then claim since there is no clear differentiation point then there is no difference? Since consciousness is a spectrum then even a rock is conscious kinda thing.

Oh man your clarity of thought is just so powerful, keep that coming. Writing is hard, but when I am not free writing to someone on the internet at 3:35am I am actually decent. Evidenced many real things in life like academia and work that severely outweighs your internet opinion which is much less useful than the artificially intelligent chatbot.

You still haven’t managed to make it clear what you used the chatbot for, or what tables you are talking about and what your children had to do with the whole thing.

What have you been doing with chatbots for “decades?” What chatbots were you using in 2003? What kind of results did you get? How were they inferior to today’s chatbots?

Sorry Joseph it was cupcakes that we made. Chatgpt helped the entire way even in the store asking questions about products.

I could write an entire chapter addressing your comment but you can search or use chatgpt to learn about the evolution of chatbots so don’t want to go into my personal experience but I guess I will if you are interested.

This is the spreadsheet chatgpt and I made:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1yye8Yzr5p358vwu9x8zGmXWd7CD6Zb4rnkoR6UKt5BA/edit?usp=drivesdk

I just asked chatgpt about evolution and history of cupcakes and nudge it around to build that spreadsheet.

Only thing next to do is fill another column automatically with the row/bay the item I need to get is in Target.