I found myself in Milton Keynes, UK, a little while ago, with a few hours to spare. What could I do but rock over to the National Museum of Computing and make a nuisance of myself? I have visited many times, but this time, I was armed with a voice recorder and a mission to talk to everybody who didn’t run away fast enough. There is so much to see and do, that what follows is a somewhat truncated whistle-stop tour to give you, the dear readers, a flavour of what other exhibits you can find once you’ve taken in the usual sights of the Colossus and the other famous early machines.

We expect you’ve heard of the classic text adventure game Zork. Well before that, there was the ingeniously titled “Adventure”, which is reported to be the first ‘interactive fiction’ text adventure game. Created initially by [Will Crowther], who at the time was a keen cave explorer and D & D player, and also the guy responsible for the firmware of the original Arpanet routers, the game contains details of the cave systems of Mammoth and Flint Ridge in Kentucky.

The first version was a text-based simulation of moving around the cave system, and after a while of its release onto the fledgling internet, it was picked up and extended by [Don Woods], and the rest is history. If you want to read more, the excellent site by [Rick Adams] is a great resource that lets you play along in your browser. Just watch out for the dwarfs. (Editor’s note: “plugh“.) During my visit, I believe the software was running on the room-sized ICL2966 via a VT01 terminal, but feel free to correct me, as I can’t find any information to the contrary.

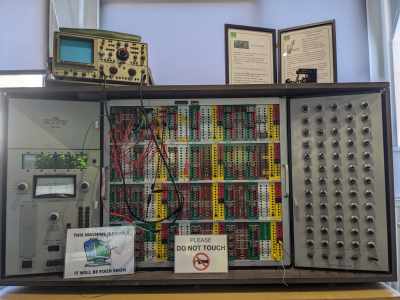

A little further around the same room as the ICL system, there is a real rarity: a Marconi TAC or Transistorised Automatic Computer. This four-cabinet minicomputer was designed in the late 1950s as a ‘fast real-time computer’, is one of only five made, and this example was initially installed at Wylfa nuclear power station in Anglesey, intended as a monitoring and alarm system controller. These two machines were spare units for the three built for the Swedish air defence system, which were no longer required. Commissioned in 1968, this TAC ran continuously until 2004, which could make it one the longest continuously running computers in the world. The TAC has 4 kwords of 20-bit core memory, a paper tape reader for program loading and a magnetic drum storage memory. Unusually, for this period, the TAC has a micro-coded CISC architecture, utilising a whole cabinet worth of diode-matrix ROM boards to code the instruction set. This enabled the TAC to have a customizable instruction set. As standard, the TAC shipped with trigonometric and other transcendental functions as individual instructions. This strategy minimized the program size and allowed more complex programs to fit in the memory.

Programs are loaded, as you’d expect, via a paper tape reader, albeit an Elliott-specific one, not a typical standardized machine. The machine’s maintainer [Peter Onion] offered to make me a custom tape using the automatic tape punch, which turned out nice.

An Elliott film handler was attached to the 803B, which is quite unusual and interesting. The story goes that the Elliott factory at Borehamwood was just ‘down the road’ from the UK film industry based at Elstree studios, so it seemed logical to adopt a 35 mm optical film format, which was modified with a coating of magnetic film, for data storage. During that period, the studios used this medium for audio track recording.

The Elliott film handler housed a single thousand-foot reel comprising 4 k data blocks, each 64 words long. Additional clocking and address tracks enable the device to seek in both directions and stop precisely where needed. The address track corresponds to pairs of blocks, depending upon the direction of travel. Odd-addressed blocks are read in the forward direction, and even-addressed blocks are read when running in the reverse direction. This leaves a whole block of space on the tape for acceleration and deceleration of the mechanism, allowing the tape to be stopped precisely where instructed. None of this shuttling back-and-forth behaviour that you see in period movies.

This means that the ‘end’ of the tape physically is block 2047 out of 4096, and the final block 4095 is back at the start of the tape. This is smart, as now you don’t need to rewind the tape to get back to the beginning for the next run. This storage device was used on earlier Elliott machines, and the 803B was the last machine to feature it before Elliott moved to industry-standard magnetic drives.

Another ‘interesting’ design choice of these machines is the power supply. It resembles a charger that might have been used for charging electric milk floats more than powering a 3.5 kW computer. On the side of the power supply cabinet is a pull-out tray with a large battery! The power supply regulation circuit differs from modern standards because it uses an AC line-side regulation strategy. It uses a saturate-able core driven into saturation with a DC feedback signal from the secondary to control the voltage on the secondary side of the main transformer. Because of this, it can only adjust to transients at a rate of 100 Hz. The large battery acts as a big smoothing capacitor and a rudimentary UPS. Neat.

There was a Pace TR-48, a transistor-based general-purpose analog computer from the late 1950s, tucked away in a side room. This machine had a typical design for an analog computer, although it was advertised as a ‘desktop’ it was more of a complete desk, with integrated storage for the removable patch panels which allowed for quickly changing the application without constant rewiring.

Push-button selectors enabled the outputs of all amplifiers, the coefficient potentiometer array and the amplifier input ‘trunks’ to be measured via one of the volt meters. The power supplies could also be monitored, and individual amplifiers could be ‘balanced’, although we’re not 100% sure what that refers to. The digital voltmeter also is reported to use ‘high brilliance optical projection’ which must look nice. Unfortunately, the TR-48 wasn’t functional when I visited. This model of computer was used by NASA during the Apollo program to simulate star systems and test the onboard star tracking systems used by the Apollo crew. Although some may argue that it was somewhat obsolete at the time, it played a significant role in the program.

Whilst I was peering over the shoulder of a nearby laptop user I did spy an interesting article about a smaller, fixed-application analog simulator, created by a team from Reading University and the Elektor Electronics lab team. The ‘chaos machine‘ is a fun simulation of the famous Lorentz system, which is a set of three ordinary differential equations which for specific parameters can exhibit chaotic behaviour. The build is easy to reproduce, provided you have a scope with an XY input mode or a suitable ADC solution. You could quickly build that on the TR-48 if you had access to one.

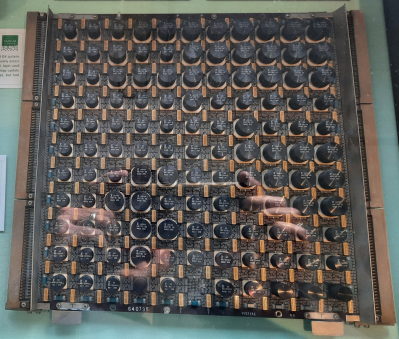

Finally, the museum has multiple exhibit rooms, hands-on platforms from the past, and numerous glass cabinets stuffed with oddities and unusual hardware we mere mortals rarely see. Check out this whopper of a CPU board, festooned with custom ECL ASICs and heatsinks, pulled from a 1985 Fujitsu series 39 mainframe. PCB designers these days rarely get to create such works of art.

We’ve covered the UK NMoC before; here’s a much earlier review. Of course, we can’t leave without circling back to the famous Colossus. That just wouldn’t be right.

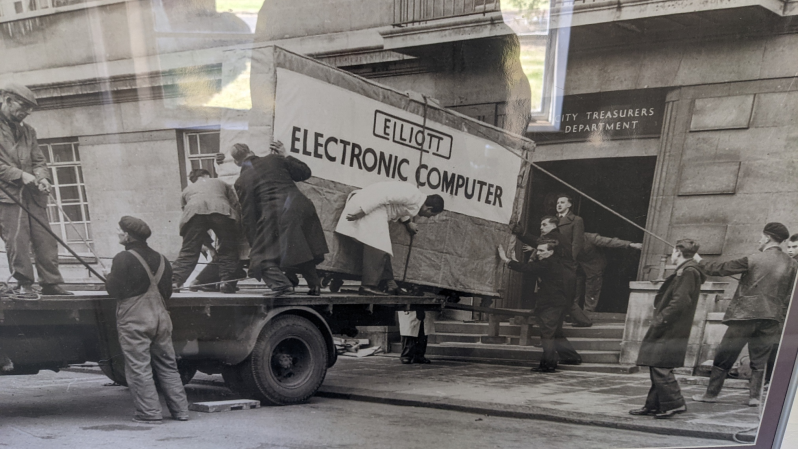

The featured image shows the Elliott computer being delivered to Norwich City Hall’s treasury department. What a trailblazer!

Nice write up. BTW for shooting photos through glass try bringing a DSLR circular polarizing filter. Even if you shot with a cell phone or point and shoot you can hold it over the lens.

Another trick is to stand well back and use a longer lens

Sometimes it’s hard to get an angle where the unwanted light is predominantly of the right polarization to be blocked, when aiming straight into a display case. Especially if you’ve got to share the room with others. And of course with phones you’re not going to get a shallow depth of field to blur the reflection, and you won’t have tilt-shift movements available. The next best thing might be to use a very wide angle – maybe a clip-on accessory if it doesn’t distort the image, though I’ve not used them – and take a picture with the object on the far edge of the frame, having stepped to the side to get out of the reflection. It’s basically the same as a lens shift, except that you must crop.

CPL lives on my DSLR all the time, that and a skylight filter. Such a cheap thing but transforms plenty of photos from OK to amazing with a twist of the filter.

I have some of that paper tape as well. I don’t recall if it was [Peter Onion] who gave it to me.

Both the National Museum of Computing, and the just next door Bletchley Park, are a fascinating day out. Honestly you could probably spend longer than a day between the two of them. I went there in the autumn of 2020 when access times were quite strictly controlled. The only thing I would have recommended was taking lunch with you, getting in the car and driving to a pub and having to wait for food felt like a bit of a waste of time when we could have enjoyed a picnic outside the mansion.

I wend to Bletchley Park a couple of years ago, and found there is a small cafe in one of the external blocks, but it was insanely busy and expensive. I’ll be taking a Tesco[1] meal-deal next time.

[1] other super market chains are available.

I’ve been to Bletchley Park once.

I have been to TNMoC several times, and will go there again when I am in the area[1]. That says everything you need to know :)

[1] e.g. after http://www.ddrcbootsale.org/

When I let Peter Onion know the 803 was the first computer I used, and that I am an electronic engineer, he reached into some drawers – and pulled out the schematics. Had a great time discussing the “weird” logic gates and architecture.

Would that happen at any other museum? Staff that really know the exhibits? Not a chance, especially not at the Bletchley Park “experience” next door.

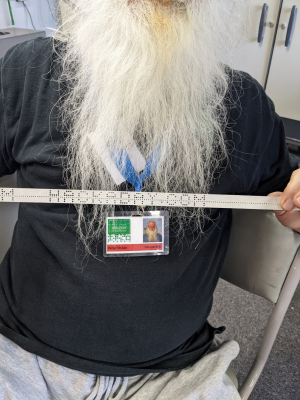

In addition, TNMoC has the world’s oldest operating computer, based on dekatrons. It also has a couple of Fuller Calculators – which were in production for 94 years and are 25.4m long[1]. I’ve just bought another, dammit.

[1] I think 12.2m is a better characterisation, with 25.4m being “sales-speak”

Awesome! I did the same. We spent nearly two hours looking over the schematics and pointing out all the oddities. That’s where the details of the odd power supply regulation came from – we were reading it off the schematics!

As for the Bletchley Park “experience” next door, that place is staffed by ex-MI5 agents throughout, pretending to be dumb as trained. If you had managed to crack the various codes that they use to identify fellow spys and code-breakers, you would have had a different and more genuine experience.

– Taps nose

– Raises newspaper with eye holes

“This is another early 1960s transistor-based machine with a hardware-efficient (but slow) bit-serial architecture. ”

https://youtu.be/nP5pztB6wPU

Well, it’s not quite the same as a bit-serial system now is it? But, a very interesting video, thanks for sharing.

“balanced” probably means adjusting the offset of the op-amp so it has zero output when the two inputs are equal.

Sure. It’s likely just that. I was thinking initially it could also be balancing one amp output with respect to another, but that would likely be described as matching, not balancing. Let’s go with your suggestion.

That’s an ICL 7161 terminal I think.

The demonstration at Bletchley is normally emulated ICL George 3 running on a Raspberry Pi.

Sometimes they run the 2966 but it takes lots of electricity and makes a decent room heater. Unlike IBM machines of the day, all ICL mainframes were air cooled. The very last versions we air cooled and used a cooling system not unlike the modern “water coolers” used on modern micros.

Fun fact: I worked ICL and for the guy who ran the 2966 project.

For any of you guys wondering about the EDSAC Replica build at TNMOC, it’s pretty close to doing arithmetic. We’ve got loops running smoothly – just need a few tweaks of delay lines to get data written back to the store in the correct bit positions – it’s all serial just like the 803, so if you get the delays wrong, the bits go into the wrong bit positions – not good for arithmetic! Us engineers are working on it most Tuesdays. Should soon have the paper tape reader installed as well. If anyone fancies volunteering to help, there are not many of us and we are ageing, so need fresh blood! No fiddling with microscopes to do surface mount work – nice big B9G base valves (US – tubes) tag strips and 3W wire ended resistors. We also have some WiFi connected logic analysers to do remote monitoring for when us volunteers can’t get out of bed – maybe some time in the future we could have people telling the staff which valve has gone down!