The city of Shenzhen in China holds a special fascination for the electronic hardware community, as the city and special economic zone established by the Chinese government at the start of the 1980s it has become probably one of the most important in the world for electronic manufacturing. If you’re in the business of producing electronic hardware you probably want to do that business there, and if you aren’t, you will certainly own things whose parts were made there. From the lowly hobbyist who buys a kit of parts on AliExpress through the project featured on Hackaday with a Shenzhen-made PCB, to the engineer bringing an electronic product to market, it’s a place which has whether we know it or not become part of our lives.

First, A Bit Of History

At a superficial level it’s very easy to do business there, as a quick trawl through our favourite Chinese online retailers will show. But when you’ve graduated from buying stuff online and need to get down to the brass tacks of sourcing parts and arranging manufacture, it becomes impossible to do so without being on the ground. At which point for an American or European without a word of Chinese even sourcing a resistor becomes an impossibly daunting task. To tackle this, back in 2016 the Chinese-American hardware hacker and author Andrew ‘bunnie’ Huang produced a slim wire-bound volume, The Essential Guide to Electronics in Shenzhen. This book contained both a guide to the city’s legendary Huaquanbei electronics marts and a large section of point-to-translate guides for parts, values, and all the other Chinese phrases which a non-Chinese-speaker might need to get their work done in the city. It quickly became an essential tool for sourcing in Shenzhen, and more than one reader no doubt has a well-thumbed copy on their shelves.

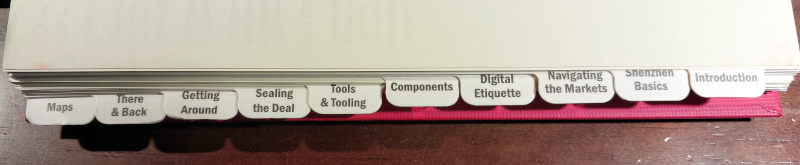

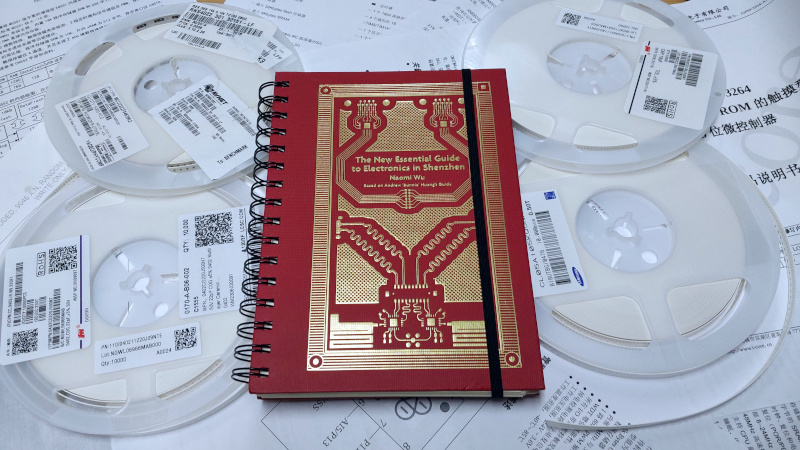

There are places in the world where time appears to move very slowly, but this Chinese city is not one of them. A book on Shenzhen written in 2016 is now significantly out of date, and to keep pace with its parts that have since chanced beyond recognition, an update has become necessary. In this endeavour the mantle has passed to the hardware hacker and Shenzhen native Naomi Wu, someone with many years experience in introducing the people, culture, and industries of her city to the world. Her updated volume, The New Essential Guide to Electronics in Shenzhen has been the subject of a recent crowdfunding effort, and I was lucky enough to snag one. It’s a smart hardcover spiral-bound book with a red and gold cover, and it’s time to open it up and take a look.

A Helping Hand For The Traveling Engineer

The first thing I did with this book was sit on the sofa and read it cover to cover, then again later in the day. Now as I have it open while I write this review it’s obvious just how every part of it is full of information. Even the introduction dives into Chinese pronunciation and what to bring with you, and then you’re into a section on the basics of being in the city and how to interact with its culture. What weather to expect, what to wear, how to take a taxi, where to eat, and even advice for any Western visitors who might be LGBT. I may be sitting in a cold and damp corner of Europe as I write this, but I’m already being prepared for my journey.

If you’re a native speaker of a European or other atonal language and you have ever encountered Chinese speech directly, you’ll know that theirs is a tonal language. If you put in a lot of effort to learn Chinese you can master the differences between the syllables as an outsider, but for those of us who have not there are many identical sounding words to our untrained ear with entirely different meanings. Naomi takes us through some of the maze of technical Chinese, and delicately reminds us through the example of “IC part number, or “xīn piàn hào”, or “芯片号” sounding similar to “xìng piān hào”, or “性偏好” which means “sexual preference”, that attempting to say Chinese words as a non-speaker can lead to pitfalls. There’s an entire section on etiquette, and in particular how it applies to the online parallel Huaquanbei through WeChat, including cultivating your image, avoiding using inappropriate emojis, and perhaps most importantly, how to master the use of the hong bao, “red envelope” system of informal gifts and payment for services rendered.

The guide is full of essential practical tips about the markets themselves. Knowing when they open versus when the booths will open, how to gather and maintain contacts, and even mealtime culture, all things which could so easily be messed up by the uninitiated. Perhaps one of the most often heard concerns about sourcing parts in China is the risk of fakes, and here there’s a comprehensive section on the various different things to watch out for, graded by impact on your project.

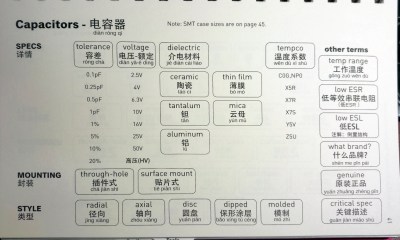

After that comprehensive introduction, we come to the main meat of the book, the point-to-translate guides. The vocabulary related to likely topics such as parts, components, tools, materials, injection moulding, packaging, shipping, and even asking for slight differences in an order is laid out in a table, with each box containing the English word, the Chinese characters, and the pinyin transliteration. I can specify a capacitor for example by turning to the relevant page, pointing to “电容器”, or “capacitor”, and then so on for the various dielectrics, packages, tolerances, and so on. I can’t fully test these pages without being in front of a Shenzhen trader ready to sell me something, however it’s clear that a lot of thought has gone into them, and the many successful users of the first edition tell me that they are pretty good. The final part of the translation guide is not related to the markets but is no less essential, a survival phrase guide for Shenzhen itself. You can take the metro, get a taxi, order food, top up your SIM, and even find a toilet armed with this guide.

Last in the book but definitely not least are a travel guide, and a comprehensively annotated series of maps dividing the Hua Quang district into a series of zones. The maps appear in two forms, a descriptive guide in English to what you should expect to find in each zone, and then a series of zone maps with point-to-translate essentials such as “Where am I?”, and “Please mark your stall on the map”. This acknowledges the many changes made to the area since 2016, but also warns that in such a fast changing city there may be future changes that might render it inaccurate.

I have spent a happy weekend immersing myself in this guide, maps of Shenzhen, and online Chinese translations to bring you this review. But of course the one thing I can’t do from here in Europe is give you a practical review in which I walk the halls of Huaquanbei and attempt to use it in the purchase of a load of parts. Thus I can only rate it on how comprehensive I find it rather than its on-the-ground usefulness. What I can say though is that the many users of the first edition found it to be of significant help, and the point-to-translate format assisted in a significant number of purchases. That coupled with Naomi’s undoubted on the ground knowledge of and enthusiasm for her native city makes this updated second edition definitely worth a look, and I can only wish you luck finding your parts and be slightly envious because my job doesn’t take me there.

The New Essential Guide to Electronics in Shenzhen, by Naomu Wu is available to pre-order now, from its crowdfunding page.

What’s the biggest difference with the previous book?

It reflects 2024 instead of 2016?

What’s the biggest difference between today’s newspaper and yesterday’s?

probably the updated maps and on-the-ground guides.

Gasp. Reading this article just cost me $40…

> and even advice for any Western visitors who might be LGBT.

lmao. The best advice is “relax”. This constant vague notion (always vague!) that China hates LGBT people exists only in the minds of people trying to push a “China bad” narrative. Please stop weaponizing our oppression. This is dehumanizing FUD meant to discourage you from meeting 1.4 billion wonderful, friendly people.

If you are Chinese your parents might not approve (more out of expectation that you will follow tradition than *phobia) but if you are a foreigner you are not going to have any problem. Seriously. The kind of hatred I experience at home broadly does not exist in China. To most Chinese, the fact I’m trans is about as interesting as the fact I have blue eyes.

Whatever dehumanizing FUD you’re referring to, you won’t find in this book, which was written by a queer Chinese person. The advice given is not at all alarmist.

This.

“The kind of hatred I experience at home broadly does not exist in China. To most Chinese, the fact I’m trans is about as interesting as the fact I have blue eyes.” Couldn’t agree more. From a westerner who’s married to a Chinese national with very close LGBT friends in a area of China where most Westerners (not as open as say Shenzhen or Beijing)

Naomi Wu, who sadly has been forced offline by her government because they do not agree with her way of life (and the fact that she finds security vulnerabilities in the most commonly used mobile keyboard software).

https://www.hackingbutlegal.com/p/naomi-wu-and-the-silence-that-speaks-volumes

Wow. Awful.

As a us startup here is what we did. We looked for a way to manufacture in the US and with local partners. The tooling costs were prohibitive. We went to CES to see who had a product we could repurpose. We discussed it with the manufacturer. They paid for all our tooling, certifications, software development. We received the products at a very affordable price, with quantity discounts available.

Its HuaQiang ;) (“China strong”)

I copied what it said in the book. I’m not Chinese, so I had to go with a book written by a Chinese person.

It’s* lol

Thought this was going to be about the Zachtronics game Shenzhen I/O, an assembly programming game that suggests you print the docs for the assembly language.