While some byproducts recall an idyllic piece of Americana, others remind us that the past is not always so bright and cheerful. Trinitite, created unintentionally during the development of the first atomic bomb, is arguably one of these byproducts.

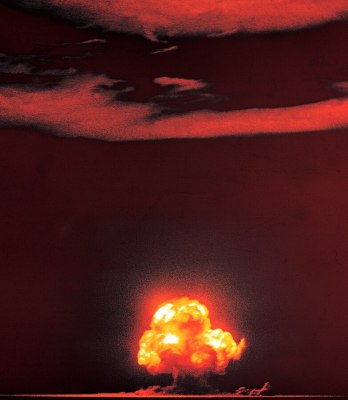

Whereas Fordite kept growing back for decades, all Trinitite comes from a single event — the Trinity nuclear bomb test near Alamogordo, New Mexico on July 16, 1945. Also called ‘atomsite’ and ‘Alamogordo glass’, ‘Trinitite’ is the name that stuck.

There wasn’t much interest in the man-made mineral initially, but people began to take notice (and souvenirs) after the war ended. And yes, they made jewelry out of it.

Although there is still Trinitite at the site today, most of it was bulldozed over by the US Atomic Energy Commission in 1953, who weren’t too keen on the public sniffing around.

There was also a law passed that made it illegal to collect samples from the area, although it is still legal to trade Trinitite that was already on the market. As you might expect, Trinitite is rare, but it’s still out there today, and can even be bought from reputable sources such as United Nuclear.

The Formation Event

On that fateful day, the plutonium bomb nicknamed “Gadget” was strapped to a 100-foot tower atop a bed of sandy soil. The detonation left a crater half a mile across and eight feet deep of radioactive glass.

While at first it was assumed that the sand that became Trinitite melted at ground level, it has somewhat recently been theorized that the sand was sucked up into the fireball, liquefied, then rained down to form a sheet of glass of varying thickness, composition, and topology.

It’s estimated that the glass was formed by 4,300 gigajoules of heat energy, and the sand was exposed to a minimum temperature of 1,470 °C (2,680 °F) and super-heated for two or three seconds before solidifying into Trinitite.

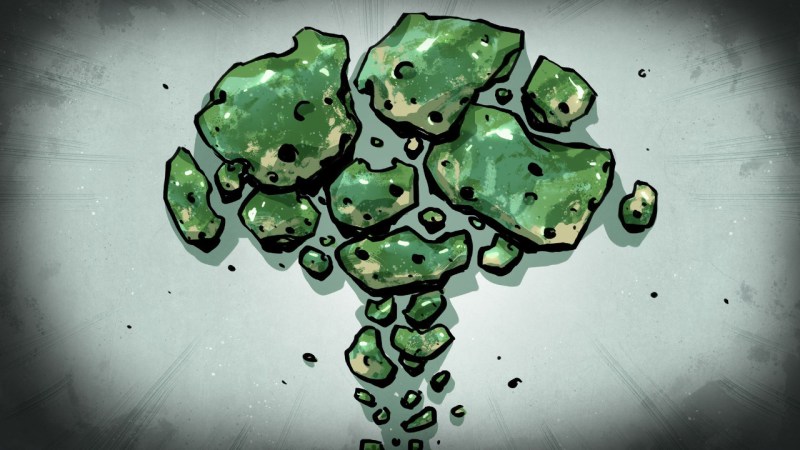

In September 1945, Time magazine reported that the site looked like “a lake of green jade”, with the glass taking strange shapes, like those of “lopsided marbles… broken, thin-walled bubbles, green, worm-like forms.” The marbles suggest that some material solidified in the air on the way down.

Not all Trinitite is bottle-green, although most of it is. Some red Trinitite was discovered in one part of the site, and there are rare black pieces that are thought to contain iron. It’s been theorized that green Trinitite gets its color from the material in the support tower, while red specimens include copper from the electrical wiring.

A Unique Composition

Geologically speaking, Trinitite is made up of a chaotic mixture that varies both its structure and composition. A typical sample has been described as 1 to 3 cm thick, with a smooth side and a rough side from landing in a molten state on the desert floor. The upper surface is usually sprinkled with dust, while the bottom is thicker and grades into the soil it came from. Far from completely solid, it is estimated that around 30% of Trinitite is void space, and usually has cracks.

Optically, there are two forms of Trinitite with different refraction indices — the lower-index type is mostly silicon dioxide, while the higher-index glass has mixed components. Although deemed safe to handle, Trinitite is measurably radioactive. The level of radioactivity fluctuates based on the size of the specimen and its distance from ground zero.

The First of Many Atomsites, Unfortunately

As you might imagine, glassy residues remain wherever nuclear weapons detonate at or near ground level. Some scientists prefer to call all other glasses ‘atomsite’, although plenty of site- and creator-specific names have been given to the byproducts of other detonations. It was discovered in 2016 that, following the bombing of Hiroshima, between 0.6% and 2.5% of the sand on local beaches consisted of fused glass spheres that had formed. It has been called Hiroshimaite.

Trinitite is known as a melt glass or glass melt, which basically means that the silica from the ground bonded with surrounding minerals originating from both the tower and the bomb itself. While this formation process is a man-made one, there are similar natural processes that produce glassy byproducts. Stay tuned!

Possibly this will be the next article in the series. Definitely not safe for jewelry —> https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chernobylite

Yep that is wayyy gnarlier for sure. At least ten thousand units of gnarly. Ten kilognarls

Not great, not terrible. :I

i enjoyed this sentence “It’s been theorized that green Trinitite gets its color from the material in the support tower”

it is awe inspiring to be reminded that things are rarely destroyed. every specimen has a specific history. even in the most chaotic event, there is some connection between the inputs and the outputs. nothing is ever really lost.

it’s related to the “bayesian search” insight — instead of guessing what happened to the missing plane and investigating along a cone of uncertainty which expands whenever a source of uncertainty is discovered (often resulting in vast search targets), they guess specific scenarios. uncertainty becomes branching scenarios, but each scenario is plotted precisely, resulting in (if you’re lucky) a somewhat larger number of much smaller search areas. we take advantage of the fact that the reality was extremely specific…we may have to consider different scenarios but the one thing that happened represents precisely one of them. really makes you think

Wow. I never thought of that.

“It’s been theorized that green Trinitite gets its color from the material in the support tower”

The first British nuke test:

“During Operation Hurricane, an atomic bomb was detonated on board the frigate HMS Plym anchored in a lagoon in the Monte Bello Islands in Western Australia on 3 October 1952.”

The blast was a water surface blast which produced a distinctly very black cloud which was iron oxide from the vaporized ship. The bottom of the area of water where it was detonated was also blackened with same.

On the Trinitite thing, I wonder how much similar stuff was produced at the national test site in Nevada where many more above ground tests were done.

Presentism gets stronger with time. “The First of Many Atomsites, Unfortunately” is a modern comment on what was a celebrated triumph and saved countless lives. One might ask, unfortunate compared to what?

I read that as less of a statement about the use of atomic weapons in combat, and more so about the literally thousands of tests that followed.

There’s modern debate about the morality of using nuclear weapons against Japan, with strong opinions on both sides. But surely few would rush to defend the decades of increasingly powerful tests performed (primarily) by the US and Soviets to see — quite literally — who’s got the bigger one.

The above ground tests were the only problematic ones with respect to radioactive fallout released into the atmosphere and after delivery accuracy was increased, the yield of the bombs was greatly reduced. Warheads like the 50 MT (100 MT capable) Tsar Bomba produced massive overkill at ground zero. Using an array of smaller bombs over an area is more efficient.

It should be valuable, I mean they’re not making any more of it, and that is a good thing.

It’s not like it’s protected or anything. It’s the literal ground at the Trinity site. I have some brought back by a coworker as a souvenir from her visit. It’s just volcanic glass, really. You know, from a location that hasn’t had volcanos in a very long time.

A piece of Trinitite would contain a trace amount of the original plutonium-239 (not all of it underwent fission in the 1945 explosion) , as well as some long-lived fission products and some activation products (see “Radioactivity in Trinitite six decades later”, Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, 85(1), February 2006, 103-120).

Do you think it would have more or fewer radioactive atoms than, say, an equivalent amount of dust from the region downwind of the prevailing winds blowing over an active coal power-plant? Obviously they would be different elements – but I was under the impression that any combustion plant (power, or maybe iron processing) released far more unstable byproduct in its exhaust over surprisingly short times.

it ain’t radioactive anymore?

Plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,100 years. So, still radioactive. Doubtful it’s in any sense dangerous though unless you grind it up real fine and eat it or inhale it.

Not that you’ld notice? I think I’ve dropped my in/near a Geiger counter and not heard anything above background from it. Unstable radioisotopes were forced into the molten glass slag that the desert surface turned into, but they’re encased in it now. Actually, now that I think of it, the waste from nuclear power plants is sometimes put through a ceramic bonding process that locks it away in the form of material dispersed through a block of glass. I wonder if the process was developed independently from first principles or if someone was inspired by what happened with Trinitite?

I’m “Galactic Stone” linked in the photo credit above. It was a pleasant surprise to see an article in trinitite on a site I have been reading for years. I’ve been lurking on Hackaday for a long time as a Linux geek and tech freak.

Trinitite is largely harmless now – just don’t eat or inhale it, and keep it away from small children or pets that might eat it.

I’ve been handling and storing kilos of trinitite for almost two decades without any ill effects. Of course, I am careful with it, but it’s largely out of a sense of general respect for radioactive materials in general and not because trinitite is particularly hazardous.

Having said that, rare random pieces will be a little “hotter” than the rest, so I check all of my samples with a Geiger counter. In almost 20 years of handling thousands of small pieces, I have run across two that were significantly more active than the average – but even still, those two pieces were not dangerously hot.

Now, if you wanna talk “hot”, I had some pitchblende ore from a mine in the former East Germany that was scary hot and I quickly sold it off to an advanced collector of radioactive minerals. I didn’t even want it in my house. LOL.

PS – here is a good article (from a now defunct website) that goes into more detail about how trinitite ended up on the private collector market : https://web.archive.org/web/20060112064847/http://www.mine-engineer.com/mining/trinity.htm