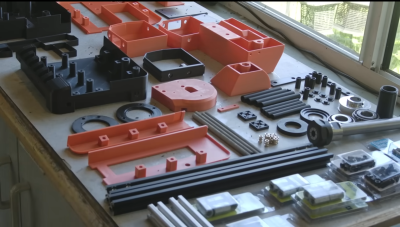

[Chris Borge] has spent the last few years creating some interesting 3D printed tools and recently has updated their 3D printable lathe design to make a few improvements. The idea was to 3D print the outer casing of the lathe in two parts, adding structural parts where needed to bolt on motors and tool holders, and then fill the whole thing with concrete for strength and rigidity.

The printed base is initially held together with two lengths of studding, and a pile of bolts are passed through from below, mating with t-nuts on the top. 2020 extrusion is used for the motor mount. The headstock is held on with four thread rods inserted into coupling nuts in the base. The headstock unit is assembled separately, but similarly; 3D printed outer shell and long lengths of studding and bolts to hold it together. Decent-sized tapered roller bearings make an appearance, as some areas of a machine tool really cannot be skrimped. [Chris] explains that the headstock is separate because this part is most likely to fail, so it is removable, allowing it to be replaced.

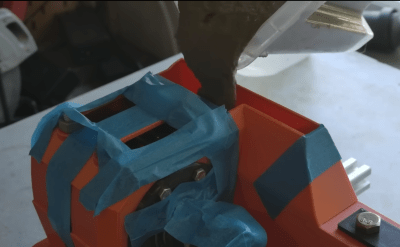

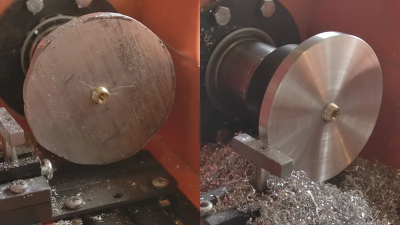

Once together, the whole assembly is filled with runny concrete and set aside to cure. Before fully curing, the top surfaces are scraped flat to remove excess concrete so the top covers will fit. A belt-driven motor is fitted, with associated control electronics, and then it’s time to talk tooling. The first tool shown is a simple T-shaped rest, used with a hand tool known as a ‘graver.’ This is more likely to be used on a wood lathe, but we reckon you could about get away with it if you’re really careful with aluminium or perhaps brass. An adjustable rest was made using a few simple pieces (in steel!) and held in a short length of 2020 extrusion in a manner that makes it adjustable, albeit not shown in this video. Finally, a reasonable torture test is demonstrated, comprising a rough-cut aluminium disk screwed to a threaded carrier. This was tidied up to make it nice and round and clean up its surfaces. The lathe survived, only melting the 3D printed motor pulley, which, as they say, should not have been a 3D printed part when metal parts are so easy to acquire! If you want to build one for yourself, then everything you need is here, but like with projects of this type, more development is still needed to overcome a few shortcomings. Check out [Chris]’s channel for many more interesting ideas!

We’ve seen a few of [Chris]’s other 3D-printed tools, like this neat fractal vice for odd-shaped objects. We like tiny tool hacks; after all, when you’re making small things, you don’t need full-sized tools.

Thanks to [CJay] for the tip!

First dont get me wrong, I like this.

But I am just curious, with companies like sendcutsend and pcbway, its so easy to get some solid steep plates to use in major parts of a build. I think the 3D printing should be for non structural components. And yes, I get it, I understand, its just I have suffered through these types of things were in the end with upgrades the original thing just not there anymore.

I appreciate how your comment was thoughtful and not just bashing. This project reminds me in a ways to the early days of 3d printers where the first company to make sheetmetal parts version of the open, 3d print as much as you can, printers met a huge amount of backlash, but eventually people were happier to have a better printer in the long run at an affordable price. Ultimately there is a middle ground.

Thank you, I really do like it, I think its great for learning, hands on, and even getting some work done. Exposing people to machines they might never get to put their hands on. Maybe next the designer can start designing in updates with some steel plates and files to order from sendcutsend etc.. I think that would be great path to 3D print yourself. And if you need better, then take the next step vs trying to hack an upgrade. again, this cool stuff :)

Hey Mike I had a question for you, What are your thoughts then on Prusa printers? I understand this is a bit different then a Lathe, but they use structural prints within their printers.

I wonder if the next revision of this will be driven by failed parts.

For example Prusa’s printers are now on their mk4 s line which has had continuous platform updates. I wonder if an organization could take the same approach for this lathe

I’m not Mike but comparing a 3D printer to a lathe is like comparing a tour de france bicycle to a dump truck. It’s an entirely different ballpark.

A 3D printer doesn’t (or shouldn’t) bump into things at force, which is what a lathe pretty much is. As a result, a printer can be made with cheaper, weaker materials. Weight also matters for a printer so printing parts is usually a better idea than actually casting them as the movement would slow down.

I was an early user of 3d printing. My first was an Anet A8 purchased as a kit from AliExpress. I’ve reinforced and upgraded so much of it now that it’s barely recognisable but that was always the intent. I really enjoy building cheap tools that transform into something better with upgrades and a lathe like this would be very tempting….if I had a use for it, which I don’t at the moment. However, awesome project.

I feel this, my first few printers were… Not great. Started with an i3 knockoff from a now defunct company that I can’t recall the name of, it was a kit printer and it was missing several components,in the end I believe I ended up spending upwards of $600 getting it up and running in addition to its initial cost. The frame was warped from the get go so it always had a vertical plant in the y axis. The second printer I got was a solidoodle press a year or so later. It was also pretty bad, so much so that they ended up being either completely disassembled for parts and then the rest was thrown out, though I do wish I’d tried remaking the press as a more robust core-xy in its shell.

To me this is more of a bootstrap type of a machine. It is functional enough to make parts for someting more substantial. It has it’s limitations but now that you have lathe you can use it to improve itself or next iterations.

It kinda negates the point of using a 3D printer to order in manufactured parts from half-way across the world. The idea is that you can do stuff with locally sourced parts instead of relying on long international logistics chains that fall apart the moment anyone sneezes.

While I agree they probably meant order in from the cheapest labour places possible the laser/plasma/waterjet cut metal plates technically they didn’t state that, just that plates with features on are easy. Which they are really even with only very basic tools, add one power drill some bits, a cutoff disk and perhaps a bandsaw and it doesn’t actually take you long to make more of these steel parts to a more than sufficient accuracy for a job like this.

So as long as you don’t decide buying in a sheet of steel of whatever thickness counts as ‘long international logistics chain’ which sadly it really could be considered as – so few nations making much if any steel anymore that lots of it is import.

I’d also have to agree with the doubt on this design – the 3d print to me should only be to hold all the embedded features in the right place relative to each other. As curing against a thin 3d print is potentially problematic for the weight and curing heat causing warping, and the relatively weak and squashy plastic remaining in so many important places on this design equally so. It works, its not a bad idea really, but without much extra effort or huge change in material and tool needs you could have a substantially better tool.

Chris is located in South Australia. Sendcutsend isn’t an option. PCBway might be, but regardless shipping tends to kill us. We’re pretty under serviced for that kind of fabrication on demand service.

Never thought of filling 3d-printed parts with concrete. Awesome project!

Just don’t use PLA. Wet cement eats right through it…

I award you 100 interwebs for making such a useful comment. 😁

I am curious to see how the extruded ways hold true and if their lack of mass leads to chatter. This seems like it would be great for light-duty work, like plastics. People bash the $300 mini-lathes(well, $600 now), but once you have them dialed-in, they work just fine so long as you understand their limits. I have two – I bought one and the seller sent me a second due to the sourcing of parts to correct shipping damage.

I have no idea how you’d even level the lathe (take the twist out of the ways so that the lathe doesn’t cut cones) when the ways are embedded in concrete.

It’s made of aluminum. Bolting it to a table and screwing one corner a little tighter will twist it the other way. A force that bends steel by 1 mm, aluminum will bend 4 mm.

maybe throwing some scrap ling metal pieces inside before concrete would be a good idea

Concrete lathes were used during the war, when we couldn’t get enough iron. Epoxy-granite concrete is used for ultra stable machine tools.

Interesting ideas.

Those old lathes were pretty solid! No pun intended.

Glad you mentioned them! Didn’t know about the epoxy-granite concrete. Is it easy to use/get?

It’s literally a mixture of granite powder and epoxy, there are some videos in YouTube about it

A quick hack to get a flat and rigid solid base for machines like this is a granite surface plate. Even cheaper is to get a sink cutout or other offcuts from a granite countertop place, these won’t be certified flat, but still overkill for moat diy machines.

looking at the potential bom, i think it would be cheaper to get one of those chinese kit lathes off of ebay. you could probibly sell a kit with everything you need except the printer/filament/concrete for an undercut price point.

Really cool idea! Love it!

I have Gingery’s books, and he points out that the lathe is the first machine tool you make, and it can make itself. (Meaning: it can bootstrap itself to a working lathe.)

Other people have pointed out that mini lathes are inexpensive, but consider: using this technique you could make a Rose Engine lathe, or a CNC lathe specific for clockwork gears, or a custom sphere cutting lathe, or a surface grinder, or a tracer lathe, or a glassblowing lathe for plastic, or any number of obscure machine tools.

You could make a CNC version that’s specific to turning a custom part for your product, and jsut use it for that one task.

Once you have the open source basis, it can be modified and extended to your specific use.

(Oh, and it looks like a nice project as well.)

I picked up a few boxes of “assorted boxes of shop gear” at an auction recently for $5 that were mostly garbage, including a couple 15-year old drills with internal batteries (obviously long dead). I recycled the batteries and was about to toss the rest when I looked at the chucks and thought “If I ever build a lathe from scratch, these will be perfect.” I figured that project was probably around 10 years away, but this is making me want to move it up on the future projects list. And I bet I can use one of the motors also.

I m working on CNC implement . hopefully i could finish the project , from there machinery like you could build a flexibility project . yes we already have firmware for cnc but it just layer 2 ,that mean the code needed debug and flexible abstract object for latter use

For a small concrete-based lathe, this is really impressive. If it weren’t for the tail of 2020 sticking out beneath the tailstock and the threaded rod/nuts, this really looks like a much larger machine. I am beginning to believe I have no excuse for not getting a 3D printer.

A used southbend lathe can be had for the same cost as the materials in this project, while being all the more capable. Still an interesting article though.

I challenge you to buy a southbend, move it, and then prove that it is more capable than this for less than the cost. ill wait.

Already did this year. Lathe itself with chuck and tooling is ~$500 (USD). Moving it isn’t hard, unless you get a large model, what I’m talking about is a 9/10″ swing. Fits in the trunk of a normal sedan so moving it is close to $0, whatever gas it takes to make a round trip I suppose.

As far as capability, it can cut 304 no problem and do everything a lathe is supposed to do.

Which is fine, but also 5-10x the cost.

his name is surealist wasteland, maybe is a hint on the conditions where you can find one for that price

I wasn’t sure whether it was the price of the South Bend lathe, or the materials used in this project, but yeah, there seems to be a discontinuity somewhere.

You can get a Southbend for $100 where you live? Wow, I never see anything for less than few thousand. Also, they are generally too big for my workshop. Most of the cheapest import benchtop lathes are 6 time this cost, the cheapest Harbor Freight one it $750. So I think this is a reasonable cost proposition. As to capability, it cuts aluminium without making a deafening racket, so it probably good enough for small work. Note he has no cross slide, so it unlike to be good for steel anyway.

This has elements similar to the Yeomans lathe of 1915.

http://flowxrgdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/new-method-of-building-lathes.pdf

Ot might have been better to use round suppored bar and ball slides for the bed (even more like the Yeomans)