We are deeply intuitively familiar with our everyday physical world, so it was perhaps a bit of a surprise when researchers discovered a blind spot in our intuitive physical reasoning: it seems humans are oddly terrible at judging knot strength.

What does this mean, exactly? According to researchers, people were consistently unable to tell when presented with different knots in simple applications and asked which knot was stronger or weaker. This failure isn’t because people couldn’t see the knots clearly, either. Each knot’s structure and topology was made abundantly clear (participants were able to match knots to their schematics accurately) so it’s not a failure to grasp the knot’s structure, it’s just judging a knot’s relative strength that seems to float around in some kind of blind spot.

Check out the research paper for all the details on how things were conducted; it really does seem that a clear understanding of a knot’s structure does not translate to being able to easily intuit which knot will fail first, even when the difference is a considerable one. There’s a video demonstration and an online version of the experiments if you’d like to try your hand at it.

It’s always interesting to discover more about our own blind spots, in part because exploiting them can result in nifty and delightful sensory illusions. We wonder if robots are any better with knots than humans?

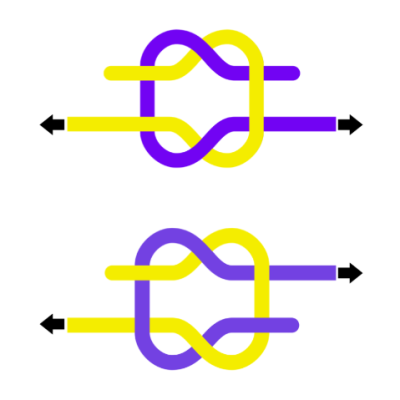

The reef knot is what you want. There are two mistakes you can do which will give you either a thief knot or a granny knot.

If you combine both mistakes you’ll get a grief knot.

If your shoelaces keep coming undone then your doing one of these mistakes.

There’s also another thing to keep in mind which is how much the knot weakens the line. Some knots are terrible in that aspect.

You do not end up with a thief knot by mistake, hence it’s original function, same goes with the grief knot, both has to be done very intentional. The granny on the other hand is the odd 99% of all people who don’t even care.

my solution was velcro shoes and slip ons. string confuses me.

The best way I have found is the technique this video details: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cBtqhq5P28

It is a bit hard to describe but you create two loops and then pass them through each other in one motion, no twisting one loop around the other which gives you the 50/50 shot of ending up with a granny knot

I find it way faster than any other method and you always get the correct square knot

Having done skateboarding, I quickly learned that the way I was taught to tie my laces in school was crap. Then started doing it this way: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6cBtqhq5P28. Always works, never unties.

I have no clue about what kind of knot it should be called, but the motion is fully imprinted in my brain. ;)

Indeed, I was rather expecting that to be the point of discussion more than the knot holding power in its own right. As that to me is the tricker bit to just work out, and less often mentioned when you look up a good knot to tie in the situation (assuming you don’t already know one for the task at hand).

Maybe it’s my construction background … but the reef knot on top would have two “load bearing” surfaces in the form of the yellow rope (and vice versa for the blue rope). So it seems “intuitively” obvious to me at least.

Maybe it’s my high school physics background. But the grief knot would tend to rotate around the moment center because the two loads are not directly opposed.

I don’t believe it’s too surprising that people don’t know their knots. While we use it in everyday life, I don’t believe it’s common to teach the subject. People who sail, or people who joined the (boy) scouts or equivalent, will likely have got themselves very familiar with all kinds of knots. I’ve taken their test, and all the knots look very familiar, even when they showed the pictures, and graphs it took me a moment to grasp the differences.

As a curious person, I just got eight pieces of 1.5mm woven polyamide cord, and practiced each knot. I do a granny knot by default, and it took me a few tried to do the others consistently. The differences are quite clear. Where the granny knot barely stays together when you pull on it, the reef knot pulls itself tight. The other tho were way worse than the granny knot.

It’s interesting to test the intuition of the participants, and I hope it helps them discover new things. However, saying people are bad at knots doesn’t feel fair. I’d be surprised if they get similar results after a quick demonstration, and giving the participants a few pieces of rope to play with. Education is everything. If we ask random people which mushroom is poisonous, we would likely not fair much better.

Don’t be so sure. Of the hundreds of scouts I’ve met over the years, there might be only 5-10 who really know their knots well. For the scout ranks, you really only need to know 4 or 5 knots anyways, which most forget soon afterwards.

I’d have suggested that because the handful of knots you really need to know will have specific features and things they are good at you should be able to figure out the correlations between topology and knot function. I don’t remember anything much of all the knots I’ve played with off the top of my head, it really isn’t worth it when 3 or 4 knots are good for every situation I’ve needed a knot in years, but that doesn’t mean the understanding of how the knots function is missing.

Same with Origami, love the stuff, invented a few of my own designs sitting in the back of English lessons mostly, got a great book on the mathematics that really solidfied the understanding of patterns I’d already developed, but can’t just remember how to fold almost anything – heck did 100 roses in two different colours wet folded for a friends wedding, it was only a few years before I couldn’t recall how to fold that rose, or even which one it might be… But I’d be able to ‘invent’ something similar relatively quickly because I still have that base understanding of the rules of the material.

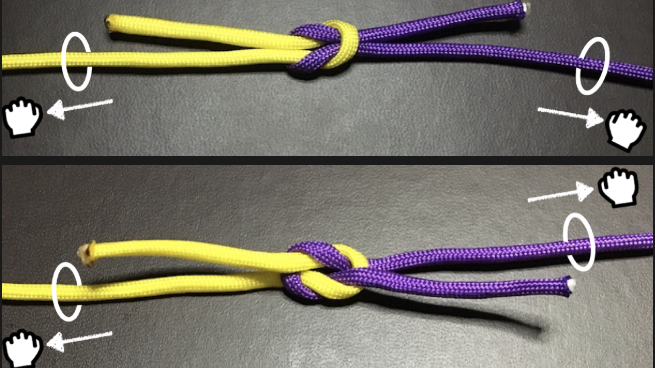

yeah this is exactly my thought…no one has an intuition for knots in the abstract. we can only have experience and training. and the best experience is to tie the knot in the rope at hand and test it for the duty in mind. for example, some knots are great on paper but won’t hold in slippery (polypropylene?) rope…and i have found that knots like the bowline hitch or sheet bend, which are highly recommended, will nonetheless loosen even in grippy cotton rope if they are subjected to alternating load in the wrong direction. there’s kind of two configurations the knot can take depending on the direction of tension (has a lot to do with which end is the loose end, like in the picture at the top of this article) and as it transitions between the two tensions, about one half-circumference worth of rope feeds through the knot

but i have been pleased to see that if you stick to like the top ten knots from a knot book, that is a small enough number you can really remember them, and every single one of them can be undone a lot easier than the kind of ad hoc series-of-half-hitches or whatever that i come up with when i’m trying to reinvent the wheel

In other news when I clearly explain fluid dynamics normal people can’t complete a problem. Math is common.

Wow big shock. Sky is blue, water is wet.

For the benefit of anyone that is curious:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ashley_Book_of_Knots

ABK is wonderful, but not really the most practical for teaching yourself to tie new knots. I would heartily recommend books by Geoffrey Budworth, or Des Pawson (I am especially partial to John Shaw’s Directory of Knots, which is spiral bound and lies flat when your hands are full of rope).

“It’s always interesting to discover more about our own blind spots”

Book recommendation: “Factfulness” by Hans Rosling.

Clears some mighty blind spots (none about knots, I’m afraid).

Flawed study. You can’t accurately judge reasoning skills based on esoteric knowledge requiring specific life experience. I’d suspect if they studied seamen from the 1800’s the researchers would have concluded that humans are geniuses at understanding knots. If these researches studied geriatrics and asked them to explain the usefulness of social media “apps” on a telephone they would conclude that geriatrics were incapable of rational thought.

Yes you can. You’re judging reasoning, not knot knowledge. They’re different.

Isn’t reasoning based on knowledge? If you already have some knowledge about a related situation can you prevent yourself from using it when reasoning about related situations? Knowledge is everything in order to be able to reason sensibly.

Reasoning is always based upon the knowledge of a relatable experience of some kind. You can’t expect people (or systems) to react seriously to situations they never encountered in some relatable form. Without a chance to try and learn it’s just a guessing game.

“Isn’t reasoning based on knowledge?”

Kindof. I’d say “the strength of common sense” or “intuition” but I hate both of those terms. Application of observations of everyday behavior to uncommon situations. Bit wordy, though.

There are lots of things that for some reason are just counterintuitive to people if they don’t study it a bunch, but almost laughably obvious to people with the right experience.

Bridges (and how they stay up or collapse) come to mind. I’d say quantum mechanics too, but public perception is that it borders on magic weirdness so it’s hard to convince people that it’s a ton more intuitive than it’s made out to be.

Not terribly surprised knots are in that group too: minor changes leading to completely different results.

Not to mention it’s difficult to draw a diagram of a knot in a way that would make it obvious which way the rope will flow and the forces will line up when you pull on it. You would have to see the knot in action to develop any proper intuition about it.

It’s like trying to explain the operation of a car engine from an exploded assembly diagram, pistons and valves floating in the air… you’d have to first mentally assemble the engine before you can start to reason about its function.

I’ve always been fascinated/slack jawed by “storage” knots. arrgh!

I.E. Those ones that mysteriously form in an electrical cord or rope, if you coil one up and toss it into a box or bag.

The last time I dropped a masons cord, it was wrapped around a pair of sticks, was stunning for how badly it was knotted when I picked it up. After fooling with it for about 15 mins, (for the 3$ cost? vs time unfouling ) It went in the trash.

I chain stitch all of my electrical cords nowdays. Put a piece of duct tape in the mid point to make it easier to just grab and start the stitch looping.

Had a couple of people try to teach me a simple way to stow ropes, but I always forget the lessons by the next time I use a rope.

Getting older and more scatterbrained taint fun.

I tend to treat electrical cords and audio cables like a lasso and carefully coil it with a quarter twist motion each round.

Chaining/daisying cable is great if you tend to throw it all in the back of a work truck. It’s not going to tangle up. But for really long cables it’s a little awkward to carry compared to 100+ feet in a neat coil over your shoulder. Putting velcro ties on 4 spots tends to keep it under control when storing. Without ties, it’s a knotted ball in no time.

That is exactly what not to do.

Putting a quarter-twist on the cables when coiling it means that you need to remove that twist when uncoiling it too. Most people don’t though and as a result, when the cable gets pulled, the wires move within the sheath and the twist becomes permanent. Eventually you end up with a cable that won’t ever lay flat and wants to coil itself in weird and wonderfully annoying ways.

The nice thing about chain-stitching cables is that any twist exerted on the cables as part of the chaining is automatically removed from it when unchaining. Another approach that works (also from the climbing world) is to use a “backpack coil”. From the audio world, the best approach to use alternating twists as you coil so that they cancel each other out when the cable is pulled straight.

That is just a true even for the toddler if the gap between being shown and needing to use it is any meaningful time you’ll forget. You have to really do it a few times to turn the concept into something you have any hope of remembering beyond tomorrow.

They ask wrong people :) They should go ask fishermen, anglers to be specific. They invented many strong knots for different situations.

the tide books we get have a page with most of the knots you will need for sport fishing.

It looks like snek. Most people do not like snek. Instinctively we avoid snek so therefore most people do not have knowledge in best way to tie snek together.

speak for yourself, i try to get as much snek as possible.

When I was a kid, we didn’t have all the new toys. Dad would bring home broken toys from the trash and had a lot of rope scraps in the garage. With our play, we discovered how ropes could be used and how certain ways of tying knots would cause them to “unroll” themselves under tension and other ways that caused the knots to self-tighten. With time, I’ve found there are even more cool ways to tie knots and to secure loads with ropes with the assistance of ratchet straps. I helped a co-worker tarp the broken back window of his car. I told him to get me 50 feet of rope, a ratchet strap, and a tarp big enough for the job. I had that tarp drum tight and the tension held with the strap so well the repair guy said he’d never seen a tarp job on a window that good. If you do any outdoor work at all, learning how to knot ropes is a great skill to have. Everything from macrame, lassos, rope climing skills, and general load securing – it’s all wonderfully fascinating to me.

Went to do the experiment, but christ, I ain’t sitting through all that. My god. If that’s the exact experiment carried out I reckon half the participants just starting mashing to get through it.

It turns out that you have to know something about a subject to have any “intuition” about it.

i only know how to tie two knots. a square knot, and a noose. the latter i learned from david caradine on wild west tech. it wouldn’t be until after his death we learned why he was so fond of that particular knot.

Presumably it took hundreds or thousands of years to develop all the different knots we use. So I’m not sure why anyone would expect knot strength to be intuitive. Especially considering that some are meant to fall apart easily.

I watch new surgeons getting trained alllllll the time. Accepting the questionable theory that medical residents are above average intelligence and seeing the huge majority of them tie granny knots over and over I can confidently say that knot tying is not intuitive at all.

The problem is that a granny is just two of the same things- two criss crosses or whatever they taught you when you learned to tie your shoes. A square knot is (for lack of a better term) a right handed then left handed criss- cross.

Presumably by that point surgeons have tied their shoes a kajillion times so learning (un-learning?) that deep muscle memory takes work.

Not exactly intuitive because only a tiny subsection of the population uses knots in any part of their life, and even when they do, usually not with any load bearing requirement. But these tests are not really of knot strength, they’re of knot “fastness” in my view. Knot strength comes down to how well the knot retains the strength of the original ropes and doesn’t induce further weakness.