There are many rechargeable battery chemistries, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. Currently lithium-ion and similar (e.g. Li-Po) rule the roost due to their high energy density at least acceptable number of recharge cycles, but aluminium-ion (Al-ion) may become a more viable competitor after a recently published paper by Chinese researchers claims to have overcome some of the biggest hurdles. In the paper as published in ACS Central Science by [Ke Guo] et al. the use of solid-state electrolyte, a charge cycle endurance beating LiFePO4 (LFP) and excellent recyclability are claimed.

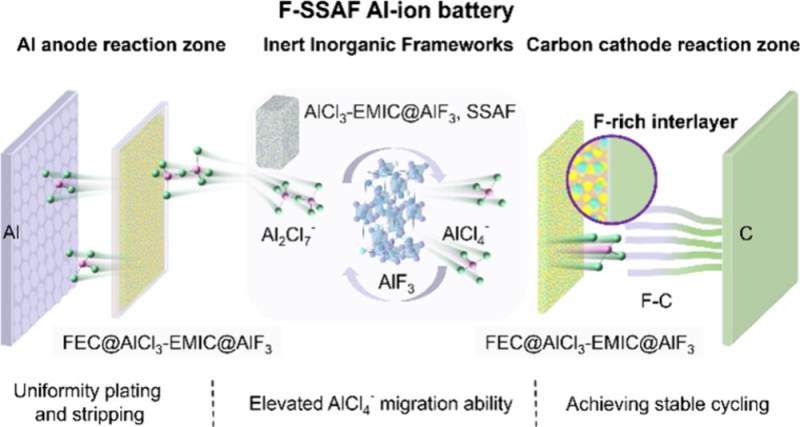

It’s been known for a while that theoretically Al-ion batteries can be superior to Li-ion in terms of energy density, but the difficulty lies in the electrolyte, including its interface with the electrodes. The newly developed electrolyte (F-SSAF) uses aluminium-fluoride (AlF3) to provide a reliable interface between the aluminium and carbon electrodes, with the prototype cell demonstrating 10,000 cycles with very little cell degradation. Here the AlF3 provides the framework for the EMIC-AlCl3 electrolyte. FEC (fluoroethylene carbonate) is introduced to resolve electrolyte-electrode interface issues.

A recovery of >80% of the AlF3 during a recycling phase is also claimed, which for a prototype seems to be a good start. Of course, as the authors note in their conclusion, other frameworks than AlF3 are still to be investigated, but this study brings Al-ion batteries a little bit closer to that ever-elusive step of commercialization and dislodging Li-ion.

All the time the same history, all on the paper, nothing on the shelves

The energy density is terribly low for those batteries, that’s why. It might be useful for energy storage for the grid, not for a car or a plane, since it has both the endurance and low cost advantage.

And again, energy storage for the grid doesn’t require batteries that last umpteen million cycles, but batteries that are extremely cheap, take very little energy to make, and can sit on the shelf virtually forever without degrading or discharging.

You want a huge battery that is charged up slowly whenever you have a surplus, to release it some time during the next year when you have a shortfall. You want to stockpile months worth of energy and keep it stored for later – to shift energy between seasons and for keeping a couple months worth of strategic reserve in case a hurricane wipes out half of your wind and solar farms. That means your big battery will only undergo a couple dozen full charge cycles in its life.

Suppose it costs $100 per kWh of capacity to make the battery, but you’ll only fully cycle it 100 times over the years. That means you pay $1 per kWh of energy stored in the battery. To make it a viable energy stockpile for the grid, it must cost less than $10 per kWh of capacity to manufacture. No battery on the market or in research is anywhere close to that price point, which is why battery storage on the grid is only good for short term load balancing where the marginal cost of electricity is high and the required storage capacity is measured in minutes and hours.

That is not what battery energy storage is for. In the Netherlands, they calculated that 8 days is the once-in-25-year maximum without solar or wind energy going above it’s avereage levels. It might vary in other climates. But battery are not meant for seasonal variations, much more for the daily peak shaving. And due to the intricacies of the power market, 500 full load cycles a year is not a weird number.

What does that even mean? Wind and solar daily averages vary significantly between winter and summer. Around those latitudes, it’s a factor of 8 or 9 from January to June. Wind power changes by a factor of 3, and the two aren’t perfectly complementary, so you get large differences in the availability of power from month to month and around the year.

The point of having a very large battery is that you don’t have to over-build your system according to minimum availability, nor rely on import/export (ironically called the “virtual battery”) and you don’t then waste any seasonal surplus for a lack of demand. E.g. little heating needs in the summer vs. little sunshine in the winter.

“Not meant for” here is simply a matter of not being suitable for – but you still need one. It’s just not immediately necessary for as long as we have ample stockpiles of fossil fuels, and big neighbors like Germany that can sell you power any time you need it.

The point of the big battery is not a backup for those odd days when you have no power, but to fit the supply and demand curves together over the long term. This keeps the marginal cost of power from going crazy and prevents the price spikes that occur every winter, and the price slumps that occur every summer.

If you have a large battery ready to accept energy, you don’t get the situation where you have to sell e.g. wind power at negative price and then pay the producer their profits from the taxpayer pocket.

In most countries the sun shines during the day… If you also need power after sunset, a battery is one way to have that. In our house which is electric only (gas-free) we use about 20kwh per day for cooking and heating/cooling with a heatpump (7200kwh per year). Mostly in summer our 10 solar panels generate (during the day) 3500kwh per year. To become entirely off grid, I would need ~ 30 solar panels and a 5Mwh battery system. And a lot of money to buy it and space to put it which we do not have in my city house. Or a perhaps windfarm and a smaller battery. The real benefit of the technology in the post is for large solar and windfarms to store surplus energy (during the day or for windfarms a couple of days) and use it when there is a shortage. It will certainly not be “seasonal storage”.

You say you need 7200 kWh per year and generate 3500 kWh during the summer. I assume that means June through August, which is 25% of the year that represents 48% of the total output. To shift that amount of energy for later in the year, you would need to store energy on the scale of at least 20-30% of your yearly total.

That is what is called “seasonal” scale storage. Instead of buffering for a day’s worth or less, you store a hundred days worth or more, so you can then supplement the availability of power gradually all through the rest of the year.

You don’t need to buy that battery because you have the rest of the electric grid for a “battery”, but when the rest of the grid goes completely off fossil fuels, it needs to build that capacity somehow. At this moment, this capacity is stored and stockpiled in the gas grids and oil refineries, or piled up at the coal plants. Only a tiny portion is held in hydroelectric dams. To become totally fossil-fuel free for that last 20-30% as a system, you need the big battery.

That, or you build nuclear.

Your choice.

Photovoltaic farms (that is what we call them here) need batteries that have more cycle times. Imagine a field of PVs that generate multiple MW and all of a sudden a cloud blocks the sun. Within a few seconds the grid looses MW or GW. Without batteries to stabilize the grid it would collapse. This stuff happens with all the PV hype.

They’re already doing that, and the grid doesn’t collapse. It just makes power grid operators very annoyed, and causes your utility bills to go up. Losing a Gigawatt in a few seconds isn’t such a big deal, since the power system is designed with “spinning reserve”. They simply load up the turbines in all the power plants like massive spinning flywheels, each contributing a small amount. This gives enough time to throttle up the burners and start up additional generators to pick up the slack.

Of course this capacity was originally meant for dealing with massive grid disturbances like losing a major power interconnect. Wind/solar power is now using this buffer as a normal part of its operation, increasing the probability that the grid will collapse on an actual fault.

To replicate the behavior and function of the spinning reserve, you don’t need a battery that is cycled rapidly. If you have a very large battery, distributed over multiple sites across the grid, a gigawatt for a few seconds or minutes would be a fraction of a percentage of one “cycle”. You’re not draining the entire battery dry every time there’s a cloud over the sun.

Mind, a “cycle” doesn’t mean changing the direction of power flow from charge to discharge and back – it counts total energy throughput in units of full battery capacity.

So a 1000 cycles for a battery means a total energy throughput of 1000 times the battery’s capacity unless otherwise specified. For the basic definition, it doesn’t matter if you use it in small portions or emptying the whole battery every time. You can keep cycling small amounts of energy in and out millions of times and the battery won’t break for that – it’s the total energy, which means the total amount of chemical reactions, that counts.

Some types of batteries don’t follow this pattern because their chemical reactions aren’t completely reversible, which is also the reason why so many of the “miracle batteries” never end up on the market. They just don’t work very well in practice.

Dude: That’s not what ‘spinning reserve’ means.

‘Spinning reserve’ is a bunch of power plants ready to start/throttle up and provide power.

In some areas it’s called ‘ready reserve’, if there is start step.

Precise definitions vary, but ‘spinning reserve’ is mostly regulatory/reporting/system planning.

Usually expected to be equal to the power of single biggest generator in the area, including transmission lines, sometime just a % of area load.

Violated all the time, everywhere.

It’s an accounting squint at the grid data.

FERC sees nothing, knows nothing…

Because they understand.

If they ‘enforce’ like an accountant, the utilities will ‘load shed’.

Code for turning off power to ‘load’ so the #s come out good.

Has nothing to do with instantaneous response.

Where the voltage is designed to give a little, power supplies designed to expect it.

Hysteresis helps.

Operations guys know spinning reserve requirements exist.

They also know they’re violated for a second/minute many times a week and there is nothing anybody can do about it.

Only counts if maintained…like a boner.

Beware negative total grid reactance day.

Switching powers supplies are evil.

I digress.

No.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operating_reserve

“The spinning reserve is the extra generating capacity that is available by increasing the power output of generators that are already connected to the power system. For most generators, this increase in power output is achieved by increasing the torque applied to the turbine’s rotor.[3]”

“The frequency-response reserve (also known as regulating reserve) is provided as an automatic reaction to a loss in supply. It occurs because immediately following a loss of supply, the generators slow down due to the increased load”

That is, immediately after losing power, the generators start to slow down and this is what applies torque on the spinning turbines. The rotating inertia or flywheel action of the turbine automatically supplies extra power to the generator. Grid operators can increase the amount of this spinning reserve by allowing the grid frequency to drop more before starting up other generators. Likewise, the grid can absorb sudden increases in supply by allowing the frequency to drift up – the extra power simply back-drives the turbines to spin faster.

Electrical usage will always change throughout the day because people use it at various times. Generation doesn’t like to follow that and sometimes can’t, but batteries can. Batteries tend to cost by the capacity and other necessary equipment by the power. But their benefit is measured in the total energy they have shifted at the end of the year, and their profit by the differences in price they were able to trade. A battery can fail to cancel variation if it’s too slow to charge or discharge, or if it hits its capacity before the variation has gone in the other direction or before something else has stepped in to take up the job. So, if you use nothing but slow rate batteries, you need way more of them, whereas if you use fast batteries with limited capacity, you can cancel out the faster variations while letting other stuff step in for the slower ones.

There is no point in energy storage on the grid. Just built an EPR or VVER and you got instant power at all times. Grid energy storage is just wasting money.

“energy density potential for aluminium-ion batteries is 1060 Wh/kg in comparison to lithium-ion’s 406 Wh/kg limit.” according to Oak Ridge National Labs, sez wikipedia.

And, given that aluminum is 5 times the density of lithium, there is the potential to make the batteries substantially smaller as well.

Aluminum is a heck of a lot cheaper than lithium too.

It will be interesting to see how this plays out.

The amount of lithium in Lion-batteries is neglegible, about 1,5%. Replacing that with aluminium isn’t gonna change that a lot.

Aluminum can also be mined pretty much anywhere in the world, whereas lithium deposits are more localized.

Thin film batteries basically triple the energy density potential of Li-Ion. The 406 Wh/kg is not the ultimate limit.

You can buy sodium-ion batteries on amazon now, for what it’s worth.

Yeah. It’s just that they’re not better than lithium-ion batteries and they’re not even cheaper for the capacity. The only advantage is that they don’t contain lithium.

So, no bursting into flames then?

Flooded cell sodium-ion batteries are fire-safe, but dry cell sodium batteries with graphite electrodes do burn quite as badly as lithium batteries do. It’s sodium you’re talking about – pour some water over it and it generates hydrogen and heat.

One actual advantage of sodium-ion is that it tolerates zero volts, so you can ship it completely discharged with no chance of shorting out and causing a fire by itself. You just don’t want to do that repeatedly, because it will damage the battery.

Although, having read some of the specs for sodium ion cells, one test condition is over-charging to 5.5 Volts and the expected result is no fire or explosion, and temperatures less than 150 C at the surface. A lithium-ion battery would turn into a bottle rocket in the same conditions.

A metal housing that turned a 18650 into a rocket would be cool Dude.

Not sure it will be able to lift itself, but worth a try.

Anybody know of previous attempts?

I’m thinking simple hollow metal tube, nozzle cut in one end cap.

Ignite by dead short.

How close to melting is acceptable?

Any guess to total heat would be a WAG, % of heat to housing still smells of dark place pulled from…

Nothing to do but ‘trial and error’, take a cell with me to the hardware store.

Stubby black pipe, plus two caps.

Won’t fly, but if it melts, then aluminum waste of time, straight to titanium.

Will look like I’m building pipe bomb, same parts list…

Should treat like a pipe bomb when testing. Rainy season in national forest.

Don’t think they can thread pipe that short…

Just find the right nipple, use shim. (love hardware store parts names).

While I’m at it, I should build a few guns for the next ‘buy back’.

Would only make the purchase even more ATF flagged.

Best use cash.

But that advantage is a deceptively big one – how many times are we not able to agree to use batteries for something because somebody gets all up in arms about the presence of the third element?

Not sure that is ever true, or any different historically – seems to me the media both technical and mainstream have latched on to batteries as the one to watch and talk about almost to exclusion of any other promising research. Not like Lithium battery went from research to in every device very quickly, and even once they did start to be common took a long while for them to be really reliable the way they tend to be now.

Depends on your definition of “quickly”. 1974 showed it was possible to make a reversible cell, 1979 saw the first practical designs, and the first commercial mass produced lithium battery came out in 1991 by Sony.

It took about 12 years from lab to market, but a big part of that delay was industry inertia. The reason why Sony started making them was because they went around the other manufacturers who actually refused to produce the battery, since they had just invested massive amounts of money in producing NiMH. It was at that time when the big corporations were buying up battery patents left and right for the second coming of the electric car, and they didn’t want a competitor coming out of the left field, so they kinda turned a blind eye on the lithium-ion battery and pretended that it didn’t exist.

“quickly” in the sense that folks seem to expect every research paper that gets media hype to be in mass production yesterday, and in their daily lives as soon as they buy a new device… Not hanging around a decade or two before that research starts to really shift into the mainstream that is very common.

But all innovations are reported (badly) like this – an early research result in a lab is reported with breathless enthusiasm by a non-scientific media, and the reporter and the reader fail to understand the many years of work ahead in actually qualifying the thing, attempting to scale up production in a practical and economically viable way, and then actually getting it to market.

It’s not a conspiracy, I’d hope readers on HaD would be smart enough to understand the process.

When the engineering team says “This is the best result yet!”, the marketing team says “This is the optimal design!”. They’re saying the same thing, but not quite.

And I thought lithium ion batteries were toxic. The SDS for fluoroethylene carbonate has all sorts of warnings.

all fairly mild however. It’s not stuff you want to cover yourself in, but it’s not really worse than what’s in a lot of batteries rn.

Lead acid batteries are a good bit more toxic by comparison.

https://aksci.com/sds/J11089_SDS.pdf

https://www.eastpennmanufacturing.com/wp-content/uploads/Wet-Batteries.pdf

fluoroethylene carbonate’s current major use is as an additive in… lithium battery electrolytes.

it literally is one of the many reasons lithium ion batteries are somewhat toxic.

.. and as far as I can tell, in both cases, it only makes up a small portion of the electrolyte. I’m not saying that magically makes it safe, just that it’s not a good indicator of relative safety here…

How small?

How many gallons of dead lithium battery squeezens would I have to distill?

How to get from this goo to ‘Ignition’ type fun with fluorine in back yard?

I have been proposing a GREAT COMPROMISE by returning to the original name for element 13, Alumium.

All in favor shout “I approvium!”

Being European, Disapprovinium!

Wernstrom!

When batteries are discussed for grid storage they talk about the density of energy storage, but real estate needs to play a part. How many batteries can be placed in a location safely for maintenance and use? How much switching is needed to ensure that maintenance will be carried out safely? How much copper are you going to have between all these storage modules.

So while grid storage with batteries may SEEM sensible, there are many considerations that make gravity storage solutions more agreeable. And more green for sure.

You have edited all the greenie hyperventilation about pumped hydro out of your memory.

Well done.

How about no? Do we really need to mass produce neurotoxic products that are bound to fail in urban environments where the human impact can be signifigant?