Although the most fire-resistant building is likely a windowless, concrete bunker, this tends to be not the vibe that most home owners go for. This is why over the years construction of buildings in areas prone to bush- and wildfires – i.e. an uncontrolled fire in an area with combustible vegetation – has adapted to find a happy medium between a building that you’d enjoy living in and a building that will not instantly combust the moment an ember from a nearby wildfire gently touches down upon any part of it.

To achieve this feat, the primary means include keeping said combustible vegetation and similar away from the building, and to make the house as resistant to ember attacks as possible. That this approach is effective has been demonstrated over the course of multiple wildfires in California during the past years, whereby houses constructed more recently with these features had a much higher chance of making it through the event unscathed.

Naturally, the devil is in the details, which is why for example the Australian standard for construction in bushfire-prone areas (AS 3959, last updated in 2018, 2009 version PDF) is rather extensive and heavy on details, including multiple Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) ratings that define risk areas and legally required mitigation measures. So what does it take exactly to survive a firestorm bearing down on your abode?

Wild Bushfires

Fire is something that we are all familiar with. At its core it’s a rapid oxidation reaction, requiring oxygen, fuel, and some kind of ignition, which can range from an existing flame to a lightning strike or similar source of intense heat. Wild- and bushfires are called this way because the organic material from vegetation provides the fuel. The moisture content within the plants and branches act to set the pace of any ignition, while the spread of the fire is strongly influenced by wind, which both adds more oxygen and helps to distribute embers to susceptible areas downwind.

This thus creates two hazards: the flame front and the embers carried on the warm air currents, with the latter capable of travelling well over a kilometer in ideal conditions. The level of threat will differ of course depending on the region, which is what the Australian BAL rating is about. As each higher BAL comes with increasing risk mitigation costs it’s important to get this detail right. The main factors to take into account are flame contact, radiant heat and ember attack, the risk from each depending on the local environment.

In AS 3959-2009 this risk determination and mitigation takes the form of the following steps:

- Look up the predetermined Fire Danger Index (FDI) for the region.

- Determine the local vegetation types.

- Determine the distance to classified vegetation types.

- Determine the effective slope(s).

- Cross-reference tables with these parameters to get the BAL.

- Implement the construction requirements as set out by the standard.

The FDI (see table 2.1) is a fairly course measurement that is mostly set by the general climate of the region in question, which affects parameters like air temperature, humidity, wind speeds and long- and short-term drought likelihoods. Many parts of Australia have an FDI of 100 – the highest rating – while for example Queensland is 40. When putting these FDI ratings next to the list of major bushfires in Australia, it’s easy to see why, as the regions with an FDI of 100 are overwhelmingly represented on it.

Vegetation Angle

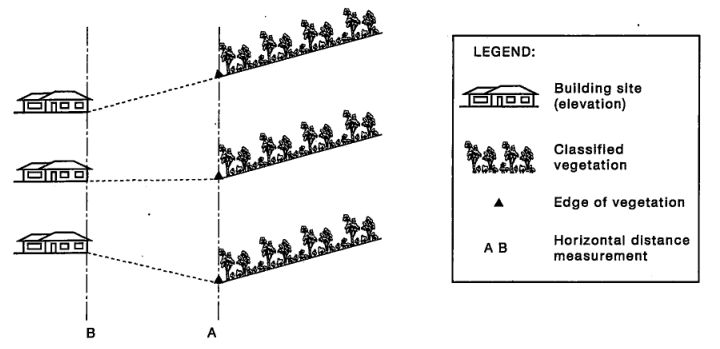

Not all vegetation types are equally dangerous, with both the distance and slope to them changing the calculation. The vegetation type classification ranges from forest to unmanaged grassland, most of which are further subdivided into a number of sub-categories, such as woodland being sub-divided into open, low or a combination thereof. This kind of classification is of course highly dependent on the country’s native vegetation.

Following on this are the edge to the thus classified vegetation, such as the beginning of the forest or shrubland, and the effective slope between it and the house or construction site. This determines how close the flame front can get, the effective radiant heat and the likelihood of embers reaching the site. If the building is downslope, for example, embers will have a much easier time reaching it than if they have to find their way upslope.

For certain areas with low-threat vegetation as well as non-vegetated areas the resulting BAL will be ‘low’, as this renders the threat from all three risk factors essentially nil.

Threat Mitigation

The BAL can thus be determined for one’s (future) abode either painstakingly using the Australian Standard document, or by using e.g. the CSIRO’s online tools for new and existing structures. Either way, next comes a whole list of mitigations, which at least in Australia are generally required to fulfill local regulations. These mitigations include any adjacent structures (garage, carport, etc.).

One exception here is with BAL-LOW, which has no specific requirements or mitigations. The first BAL where measures are required is BAL-12.5, which has to cope with ember attack, burning debris and radiant heat up to 12.5 kW/m2. The next two levels bump this up to 19 and 29 kW/m2, before we get the final two levels that include the flames reaching the building either intermittently (BAL-40) or engulf fully (BAL-FZ, i.e. Flame Zone).

Regardless of the BAL, most of the mitigations are rather similar:

- any external surfaces exposed to potential embers, radiant heat and/or flames shall be either non-combustible, or bushfire-resistant.

- gaps and vents larger than 3 mm must be covered with a (bushfire) mesh that has a maximum aperture of 2 mm.

- installation of bushfire shutters to protect windows and doors.

- non-combustible roof tiles, sheets, etc.

One aspect that differs here is the setback distance, which for BAL-FZ is at least 10 meters between the house and the classified vegetation, which is less stringent with the other BALs.

Common Sense

Many of these measures are common sense, albeit it that the devil is in the details. What the right type of bushfire mesh or sealant is to keep embers out, for example, or the best kind of siding. Fortunately this kind of information is readily available, which makes a solid assessment of one’s abode the most crucial step. Perhaps the most crucial one after assessing gaps is the removal of flammable material near the house, including bushes and other vegetation, and the consideration of what’d happen if any part of the house exterior got exposed to embers, radiant heat and/or flames.

So-called wall and roof penetrations like skylights, AC units and ventilation can inadvertently become welcoming entrances. This plays a major role in the US, for example, where attic venting is very common. Without mesh keeping embers out, such vents will do what they’re designed to do, which is circulating (ember-filled) outside air. Generally the local fire department in bush- and wildfire prone areas will have resources to help hardening one’s home, such as CalFire’s dedicated resource site.

Although keeping up with these defenses is not super-easy, it bears keeping in mind that in the case of a major fire it can only take a single ember to compromise every other measure one might have taken. Since big fires do not generally announce themselves weeks in advance, it’s best to not put off repairs, and have a checklist in case of a wildfire so that the place is buttoned up and prepared when the evacuation notice arrives.

Though following all mitigations to the letter is no guarantee, it will at least give your abode a fighting chance, and with it hopefully prevent the kind of loss that not even the most generous fire insurance can undo.

Featured image: “Deerfire” by John McColgan

“non-combustible roof tiles, sheets, etc.” this seems a big one. As is not covering the outside of your plywood built house with vinyl.

Just a few ideas.

More reasons why vinyl (windows, siding, & pipes) should be banned.

Common sense, don’t built houses from lumber USA, see EU houses. Funny thing they cost the same.

lumber is carbon neutral, concrete is usually not. Otoh, sheetrock panels are made from fluegas waste products, so not very carbon neutral too.

Sure, lumber is almost carbon neutral to grow, not to build with, and even more if you had to build twice.

Concrete is neutral since it doesn’t emit CO2, it’s the furnace used to bake cement that emit CO2. And those can run on any other energy than burning charcoal, like nuclear or electricity, since it’s only heat that’s required and any thermal source would do.

Even an electric furnace making cement produces CO2. Limestone has CO2 in it.

Interestingly, my house built with lime, then reabsorbs this CO2 from the atmosphere, hardening the lime. Win-win!

Production of concrete, at least Portland concrete produces heaps of CO2 and is a major contributor to global CO2 emissions.

https://www.usgs.gov/news/featured-story/heating-limestone-a-major-co2-culprit-construction

Well, I´m surprised that this website was not erased. Not yet.

It is “better” than carbon neutral. It sequesters carbon – unless it burns or rots.

In numbers, building a U.S. house can emit ~7.5 – 12 metric tons CO₂, whereas an European house ~45 – 75 metric tons. Basically, building a brick-and-mortar house in Europe can emit 4 to 6 times more CO₂.

The fact that European buildings last considerably longer does not offset this difference (it’s a difficult calculation since they HAVE NOT lasted 4 to 6 times more, but they COULD). It gets even worse when you take heating into consideration as it’s easier to isolate a wood-framed building.

That’s at least in theory, as after the house is built the US folks use DOUBLE the amount of energy anyway, but that’s a different topic.

My UK house predates the existence of the US of A. So – IT HAS.

Have you compared houses from similar temperature zones ? The criteria for a house north of the pole circle is wastly different from something built in the american south.

Plus, per square foot.

Euro houses are tiny, American houses often ridiculous.

You should see the bodges used in Germany to pretend their not just doing exposed wiring everywhere they revised anything. White plastic snap together ‘conduit’ with pre-attached tape ‘kits’.

But a brick-and-mortar house is a higher level of quality. The firewood houses are like a hard coated tents: you can hear every step at night when the wood is whining under your foot, if you fall and hit the wall the wall will probably break, and full of voids to accommodate insects and pets.

*pests

Can’t build homes from concrete in California. Earthquakes. For example take a look at photos of the cypress structure after the big quake in ’89.

You definitely can. A elevated highway is not a house. Proper foundation anchoring and well attached shear walls will go a long way to mitigating seismic structure damage and concrete residential buildings, properly designed and built, do a better job than wood frame houses.

And concrete doesn’t flex. When building a house you lay down your foundation and attach your walls to it. That creates a stress point. The stress point will try to flex during an earthquake. In that scenario the concrete will break no matter how you try to secure it to the foundation. The building I work in has a foundation with floating points for the 5-story structure. The building is concrete and those floating points absorb the flex from earthquakes. It works. Buying a house with that feature, however, isn’t feasible because it would likely double or triple the selling price.

You can build concrete structures using forms and reinforcement in California. That’s totally legit. But they’re super ugly to have as a home. And not cheap to get compared to alternatives when dealing with residential home sized structures.

The internal plumbing and wiring is kind of a pain in these. And it is difficult to meet county code in a residential structure because the code is so far behind the technology.

Building out of traditional brick, especially the way bricklayers in the US do it, makes an unsafe structure in earthquake conditions. I wouldn’t recommend it for new buildings.

Not all of EU builds from bricks. Where i live, a lot of houses are built with wood. There’s lots around, so why not use it. Most likely cheaper too. My house has only the basement made of concrete. The 2 floors above are wood.

But sure, if i lived in California (which is one of the last states i would choose to live in), i’d get a stone house from an area where i can prepare for a fire and try to prevent it from burning down the house.

Forget houses, I doubt even a shed would be affordable here if it had to be concrete or brick.

Bricks and steel or tile roofs. Some parts of the country have a lot of brick. Abilene Texas is primarily brick. Openings to eves need to be handled due to high wind driven flames and embers. Get rid of vegetation rear the structure. It is just a place for burglars to hide or work unseen.

What about trees? I like to see the sky and don’t care for them or the damage they do, but realtors think they are a huge deal. “Several mature trees” is a selling point. Waiting to see analysis from California on homes that survived among those that burned.

After the Great fire of London they promoted building in brick and stone. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rebuilding_of_London_Act_1666

Take a peek at downtown Santa Cruz on October 17, 1989 to see what brick buildings are like here.

Oh fair point! Well guess you have to take a gamble or choose what is least likely.

In seriousness hoping folks who lost everything get insurance or some state support

Some parts of Boston (the U.S. one) are quite acceptable.

+1

All well and good for typical house fires. But for a conflagration it’s useless. Source: my house burned down in CA and the steel I beam over the garage was sagging and all the concrete was burned into powder. Silver in the “fire safe” was melted into a puddle.

.

Maybe for the penumbra area around the edges things like hot ember mitigation would be helpful to slightly decrease the burn area. But for a “real” fire beat you can do is hire a large claims lawyer and try to go from there.

I always wondered whether you could just store old milk cartons filled with water in the loft/attic, and have a sprinkler system for the roof fed from your pool. Of course you’d also need a generator to run the pump, because likely the electricity would go off.

If you could fit roughly 90 cubic metres of water in your attics milk cartons, you are golden. Otherwise, Fuhgeddaboudit.

Cardboard cartons? Hmm haven’t tried that. But, being a Pyro, once but a plastic bottle of alcohol (99% IPA) on a fire. Note the bottle wasn’t full, and the cap wasn’t on. Amazingly the lower half of the bottle never melted, the surface layer of alcohol just burned continuously. I always liked the idea of having a plastic reservoir above, say, lithium batteries contained in a tub, so that it would melt the reservoir and fill the tub in the event of a fire. Violently impractical unfortunately, and based on my one inadvertent test probably not viable anyway

I think you might be trying to fix the wrong problem.