Perhaps one of the clearest indications of the Anthropocene may be the presence of plastic. Starting with the commercialization of Bakelite in 1907 by Leo Baekeland, plastics have taken the world by storm. Courtesy of being easy to mold into any imaginable shape along with a wide range of properties that depend on the exact polymer used, it’s hard to imagine modern-day society without plastics.

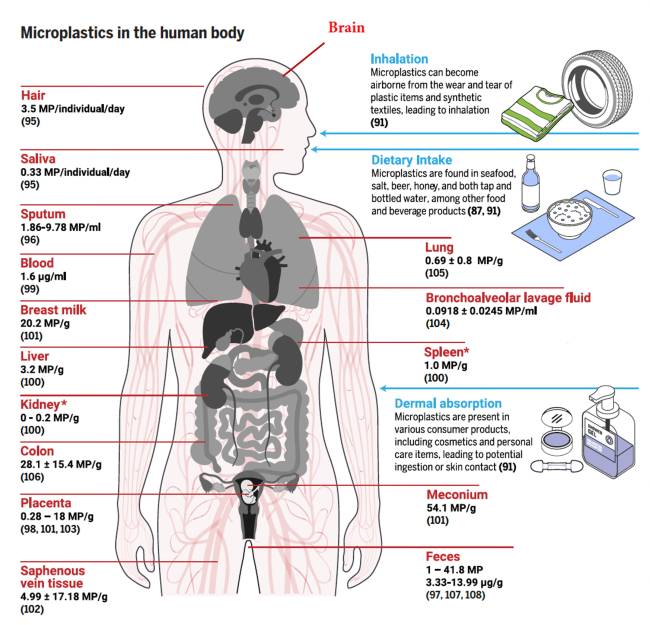

Yet as the saying goes, there never is a free lunch. In the case of plastics it would appear that the exact same properties that make them so desirable also risk them becoming a hazard to not just our environment, but also to ourselves. With plastics degrading mostly into ever smaller pieces once released into the environment, they eventually become small enough to hitch a ride from our food into our bloodstream and from there into our organs, including our brain as evidenced by a recent study.

Multiple studies have indicated that this bioaccumulation of plastics might be harmful, raising the question about how to mitigate and prevent both the ingestion of microplastics as well as producing them in the first place.

Polymer Trouble

Plastics are effectively synthetic or semi-synthetic polymers. This means that the final shape, whether it’s an enclosure, a bag, rope or something else entirely consists of many monomers that polymerized in a specific shape. This offers many benefits over traditional materials like wood, glass and metals, all of which cannot be used for the same wide range of applications, including food packaging and modern electronics.

Unlike a composite organic polymer like wood, however, plastics do not noticeably biodegrade. When exposed to wear and tear, they mostly break down into polymer fragments that remain in the environment and are likely to fragment further. When these fragments are less than 5 mm in length, they are called ‘microplastics’, which are further subdivided into a nanoplastics group once they reach a length of less than 1 micrometer. Collectively these are called MNPs.

The process of polymer degradation can have many causes. In the case of e.g. wood fibers, various microorganisms as well as chemicals will readily degrade these. For plastics the primary processes are oxidation and chain scission, which in the environment occurs through UV-radiation, oxygen, water, etc. Some plastics (e.g. with a carbon backbone) are susceptible to hydrolysis, while others degrade mostly through the interaction of UV-radiation with oxygen (photo-oxidation). The purpose of stabilizers added to plastics is to retard the effect of these processes, with antioxidants, UV absorbers, etc. added. These only slow down the polymer degradation, naturally.

In short, although plastics that end up in the environment seem to vanish, they mostly break down in ever smaller polymer fragments that end up basically everywhere.

Body-Plastic Ratio

In a recent review article, Dr. Eric Topol covers contemporary studies on the topic of MNPs, with a particular focus on the new findings about MNPs found in the (human) brain, but also from a cardiovascular perspective. The latter references a March 2024 study by Raffaele Marfella et al. as published in The New England Journal of Medicine. In this study the excised plaque from carotid arteries in patients undergoing endarterectomy (arterial blockage removal) was examined for the presence of MNPs prior to the patients being followed to see whether the presence of MNPs affected their health.

What they found was that of the 257 patients who completed the full study duration 58.4% had polyethylene (PE) in these plaques, while 12.1% also had polyvinyl chloride (PVC) in them. The PE and PVC MNPs were concentrated in macrophages, alongside active inflammation markers. During the follow-up period during the study, of the patients without MNPs 8 of 107 (7.5%) suffered either a nonfatal myocardial infarction, a nonfatal stroke or death. This contrasted with 30 of 150 (20%) in the group with MNP detected, suggesting that the presence of MNP in one’s cardiovascular system puts one at significantly higher risk of these adverse events.

The presence of MNPs has not only been confirmed in arteries, but effectively in every other organ and tissue of the body as well. Recently the impact on the human brain has been investigated as well, with a study in Nature Medicine by Alexander J. Nihart et al. investigating MNP levels in decedent human brains as well the liver and kidneys. They found mostly PE, but also other plastic polymers, with the brain tissue having the highest PE proportion.

Interestingly, the more recently deceased had more MNP in their organs, and the brains of those with known dementia diagnosis had higher MNP levels than those without. This raises the question of whether the presence of MNPs in the brain can affect or even induce dementia and other disorders of the brain.

Using mouse models, Haipeng Huang et al. investigated the effects of MNPs on the brain, demonstrating that nanoplastics can pass through the blood-brain barrier, after which phagocytes consume these particles. These then go on to form blockages within the capillaries of the brain’s cortex, providing a mechanism through which MNPs are neurotoxic.

Prevention

Clearly the presence of MNPs in our bodies does not appear to be a good thing, and the only thing that we can realistically do about it at this point is to prevent ingesting (and inhaling) it, while preventing more plastics from ending up in the environment where it’ll inevitably start its gradual degradation into MNPs. To accomplish this, there are things that can be done, ranging from a personal level to national and international projects.

Clearly the presence of MNPs in our bodies does not appear to be a good thing, and the only thing that we can realistically do about it at this point is to prevent ingesting (and inhaling) it, while preventing more plastics from ending up in the environment where it’ll inevitably start its gradual degradation into MNPs. To accomplish this, there are things that can be done, ranging from a personal level to national and international projects.

On a personal level, wearing a respirator while being in dusty environments, while working with plastics, etc. is helpful, while avoiding e.g. bottled water. According to a recent study by Naixin Qian et al. from the University of California they found on average 240,000 particles of MNPs in a liter of bottled water, with 90% of these being nanoplastics. As noted in a related article, bottled water can be fairly safe, but has to be stored correctly (i.e. not exposed to the sun). Certain water filters (e.g. Brita) filter particles o.5 – 1 micrometer in size and should filter out most MNPs as well from tap water.

Another source of MNPs are plastic containers, with old and damaged plastic containers more likely to contaminate food stored in them. If a container begins to look degraded (i.e. faded colors), it’s probably a good time to stop using it for food.

That said, as some exposure to MNPs is hard to avoid, the best one can do here is to limited said exposure.

Environmental Pollution

Bluntly put, if there wasn’t environmental contamination with plastic fragments such personal precautions would not be necessary. This leads us to the three Rs:

- Reduce

- Reuse

- Recycle

Simply put, the less plastic we use, the less plastic pollution there will be. If we reuse plastic items more often (with advanced stabilizers to reduce degradation), fewer plastic items would need to be produced, and once plastic items have no more use, they should be recycled. This is basically where all the problems begin.

Using less plastic is extremely hard for today’s societies, as these synthetic polymers are basically everywhere, and some economical sectors essentially exist because of single-use plastic packaging. Just try to imagine a supermarket or food takeout (including fast food) without plastics. A potential option is to replace plastics with an alternative (glass, etc.), but the viability here remains low, beyond replacing effectively single use plastic shopping bags with multi-use non-plastic bags.

Some sources of microplastics like from make-up and beauty products have been (partially) addressed already, but it’d be best if plastic could be easily recycled, and if microorganisms developed a taste for these polymers.

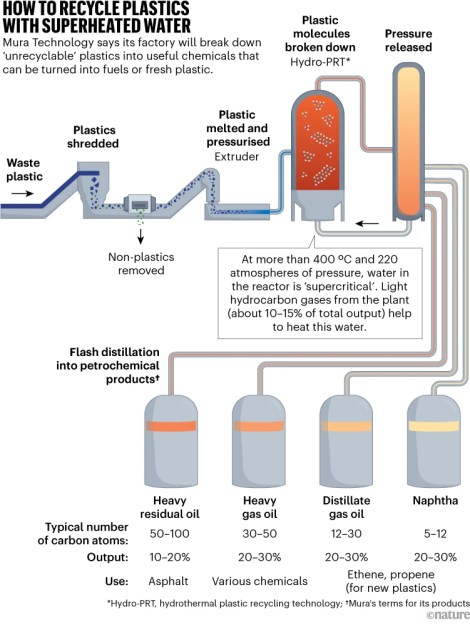

Dismal Recycling

Currently only about 10-15% of the plastic we produce is recycled, with the remainder incinerated, buried in landfills or discarded as litter into the environment as noted in this recent article by Mark Peplow. A big issue is that the waste stream features every imaginable type of plastic mixed along with other (organic) contaminants, making it extremely hard to even begin to sort the plastic types.

The solution suggested in the article is to reduce the waste stream back to its original (oil-derived) components as much as possible using high temperatures and pressures. If this new hydrothermal liquefaction approach which is currently being trialed by Mura Technology works well enough, it could replace mechanical recycling and the compromises which this entails, especially inferior quality compared to virgin plastic, and an inability to deal with mixed plastics.

If a method like this can increase the recycling rate of plastics, it could significantly reduce the amount of landfill and litter plastic, and thus with it the production of MNPs.

Microorganism Solutions

As mentioned earlier, a nice thing about natural polymers like those in wood is that there are many organisms who specialize in breaking these down. This is the reason why plant matter and even entire trees will decay and effectively vanish, with its fundamental elements being repurposed by other organisms and those that prey on these. Wouldn’t it be amazing if plastics could vanish in a similar manner rather than hang around for a few hundred years?

As it turns out, life does indeed find a way, and researchers have discovered multiple species of bacteria, fungi and microalgae which are reported to biodegrade PET (polyethylene terephthalate), which accounts for 6.2% of plastics produced. Perhaps it’s not so surprising that microorganisms would adapt to thrive on plastics, since we are absolutely swamping the oceans with it, giving the rapid evolutionary cycle of bacteria and similar a strong nudge to prefer breaking down plastics over driftwood and other detritus in the oceans.

Naturally, PET is just one of many types of plastics, and generally plastics are not an attractive target for microbes, as Zeming Cai et al. note in a 2023 review article in Microorganisms. Also noted is that there are some fungal strains that degrade HDPE and LDPE, two of the most common types of plastics. These organisms are however not quite at the level where they can cope with the massive influx of new plastic waste, even before taking into account additives to plastics that are toxic to organisms.

Ultimately it would seem that evolution will probably fix the plastic waste issue if given a few thousand years, but before that, we smart human monkeys would do best to not create a problem where it doesn’t need to exist. At least if we don’t want to all become part of a mass-experiment on the effects of high-dose MNP exposure.

Why isn’t this movie mentioned? https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9071322/

Is HaD being silenced by 3M company?

3M merged with M&M Mars. The new company? Ultradyne systems. (Simpsons or Futurama?)

Or use it as feedstock for energy production and go back to Glass and paper. When I was young plastic was rarely a food container or a bag option. Paper and glass are much better alternatives. Bring them back.

Nothing to do with the amount of plastic found in my brain, or actually maybe the thought was caused by the amount of plastic in my brain, but I wonder what the plastic-provided reduction in packaging weight per unit of volume has done for the fuel efficiency of food and beverage transportation?

Thinking mainly about glass. Waste/loss has probably been reduced some, too.

Aluminum would actually be a better option in a lot of cases.

Looking at Pripyat these days, nuclear war might even be a better option on a long enough timescale. That place is lush, primarily because people and industry won’t go there in significant numbers anymore.

Isn’t aluminum also dangerous due to aluminum poisoning?

Aluminum cans are lined with a layer of plastic. It protects the aluminium from being corroded but tends to leak lots of BPA (an endocrine disrupting plasticizer)

Not sure how much plastic is used in paper manufacture. I tried a web search to find composition of paper used in tea-bags (for I’d wager there’s some polymer in there at the very least to seal the edges), but couldn’t find any information. If anyone reading this knows about plastic uses in paper manufacture (especially teabags), I’d be all ears!

The composition of teabags varies by brand. Mostly they’re filter paper but they can have a plastic liner or sealant around the edges. Others are nylon, PLA, or even silk.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tea_bag

Thank you!

Interesting to hear of the silk tea bag.

I think part of the trick might be understanding which filter-papers use plastic in their composition.

The stupid pyramids are 100% micro-perforated plastic. Avoid at all cost.

Yes, you are right to be concerned. Many studies have shown that there are huge amounts of micro- and nano-plastics in a cup of tea (up to 11 billion in a single cup). As Paul LeBlanc commented, even paper teabags still use plastic glue and edge sealants. These plastic sealants are used so that the adges of the bag can be quickly and economically heat-sealed.

There are lots of studies showing up on a quick Google search, for example:

https://www.implasticfree.com/why-you-should-switch-to-plastic-free-tea-bags/

Thank you for the tip!

The ones that sound to me from that list like they’re plastic free are:

Nature’s Cuppa Organic Tea Australia, Stash Tea USA, Pukka UK, Maybe teapigs (“use cornstarch” but cornstarch can be a feedstock for PLA manufacture so unclear wording to my mind) UK, Tetley Tea Australia String and Tag Teabags (?UK too), Uncle Tea teabags… ?country, Bromley of North America.

I will try to find out if Tetley UK String and Tag teabags are plastic free. That would be a coup. I lament that Pukka aren’t very affordable as a “daily driver”.

Get an infuser and some better tea.

‘Tea bags’ are just a bad idea.

Like coffee pods.

Useless waste for a bad product.

Allowing plastics to be involved with the food industry is one of the greatest failings of humanity in the past century. Everyone must eat daily. Plastics being involved with food means that plastic trash is produced multiple times per day by everyone who eats… 100% of humanity. If we cut plastic out of the food industry, we will see a huge reduction in consumed plastic particles of every size. The only reason not to do so is corporate profits.

There are some tea bags that are certified plastic free.

Thank you! This prompted me down a most interesting rabbit-hole.

Reading articles such as these:

https://www.countryliving.com/uk/food-drink/a3291/plastic-tea-bags-environment/

https://moralfibres.co.uk/the-teabags-without-plastic/

I was fascinated to read commentary such as: “Thanks to consumer demand, Clipper took action, and switched its pillow teabags to a plant-based PLA [plastic] several years ago, sourced from non-GM plant material.”

If I accept https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969722021076 at face value, in saying “Even though PLA is a biodegradable polyester, it actually degrades under specific composting environments, including a rich oxygen environment with high temperatures (58–80 °C), high humidity (>60% moisture) as well as the presence of micro-organisms (thermophilic bacteria).” then I am not wholly sure this would protect the tea-drinker from any threat that might arise from PLA ingestion.

I remain grateful for any steer regarding where to find “truly” plastic-free teabags. My websearch-fu, alas, continues to fail me.

Pukka brand teabags sound like they really are plastic free… I.E. not even PLA, nor even plastic in the ingredients from the paper manufacturer.

https://www.pukkaherbs.com/uk/en/wellbeing-articles/pukkas-sustainable-packaging

Food service paper can / does contain PFAS.

I was just surprised to find out that the best and most environmentally way for the home hobbyist to dispose of PLA printing filament may be to burn it. Wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polylactic_acid#End_of_life

(Or an expensive machine to grind it up and re-extrude it into poop-brown new filament. You’d have to make a lot of rolls to pay for the machine.)

Important: This only applies to PLA, not to PETG, ABS, ASA, and other filaments.

Or turn it into powder and reprint the plastic: https://hackaday.io/project/181165-direct-granules-extruder-fdm-prints-from-powder

If you’ve got curbside compost pickup there’s a semi-decent chance it’s going to an industrial compost facility big enough to break down PLA

Into MNPs, no?

According to the Wiki link posted by Doctor Wizard, PLA is fairly biodegradable. This was my understanding of PLA as well.

Recycling plastic has another issue: some types are not economical or profitable. Companies will rather go with cheaper stuff, and with most plastic types, virgin plastic is often cheaper than recycled plastic.

Plastic recycling is nearly 100% fake. Sorting and taking out plastic recycling is a bizarre German religious practice which was exported to a few other parts of the globe.. It has no bearing on reality.

I applaud this article. Thank you for writing it!

If it doesn’t break down much over 1000 years or whatever in a land fill I’m not going to lose sleep over it being in my CNS.

A piece of lead jacketed with copper will last for centuries without breaking down, but I don’t want it in my CNS either. Reactivity isn’t the whole story

Here’s a huge route for it into our systems: OUR CLOTHES.

I recently moved into a room facing bright morning sun. In the morning I go to grab a freshly washed shirt to put on.

And the sunlight makes me realize: CLOUDS of particles come off the freshly laundered clothing when I pull it off the hanger and give it a shake.

They’re not dirty, it’s not dust. It’s minuscule pieces of the fibers that shed mostly after having washed the clothes.

We’re breathing the plastic particles that shed from our clothing. I think this is the primary route for it to get into the brain (via the olfactory bulb).

I almost wish I didn’t see this because I was comfortable in my ignorance before. I don’t want to change my entire wardrobe. But every morning when I go to put on a shirt… poof, I see the clouds of particles.

I read this and thought “Why do his clothes do that? Mine never do that” but then I realised that most of my clothes are cotton

There is a guy in Australia, producing the series War on Waste. He had his excrement tested for microplastics, and turns out the majority of them were from his clothing.

“Just try to imagine a supermarket or food takeout (including fast food) without plastics.”

Fish and chips are still wrapped in paper, as is McDonald’s etc. many Chinese takeaways use foil cartons with card lids.

Supermarkets used to use far more paper/card packaging. (Though some plastic packaging reduces waste e.g. shrink wrapped cucumbers reduce waste very significantly).

Are you more willing to endure plastic waste or biodegradable organic waste? I vote waste some cucumbers and halt the plastic waste.

There is no avoiding the organic waste… Hopefully. It would be alarming if we suddenly didn’t have that

While I agree paper and cardboard is used for a lot of fast food, how many of those paper bags or containers are plastic lined? Particularly with larger fast food chains. Try to rip the drink containers and I guarantee most are plastic lined (not waxed). And plastic straws are making a comeback!

In some places plastic single use utensils, including straws, are illegal. The biodegradable replacements sucked for a year or so, but now they’re functionally equivalent.

I don’t have to imagine it; I was alive a few decades ago. Every liquid in the grocery store was in glass. It’s amazing how things which we have done just fine–after the advent of computers, after man walked on the moon–as being impossible to manage or return to.

Untrue. Most types of plastics do biodegrade with a half-life of months. The difference is that macroscopic particles are hard to break down because the organisms and their enzymes attach to the ends of polymer chains which are inaccessible in large particles, but readily available in micro- and nanoparticles of plastic. The biological half life speeds up as the plastic breaks down to smaller sizes. E.g. rubber tire dust along roads is eaten up over the course of a year – even the synthetic kind.

The confusion comes from the definition of “microparticles” which includes pieces up to 3 mm in size, which is a massive piece in terms of bacteria. A whole plastic bag thrown in the woods takes decades to disappear. When you count these particles in the mix, it indeed looks like microparticles don’t biodegrade significantly, but these particles are eventually broken down mechanically and photochemically to the point that they become food to soil bacteria and fungi.

I’m sorry, but there is no analysis here of what happens to cellulose, which is arguably the most widely dispersed polymer on the planet. It is created by plants, so we eat them, digest them, and excrete them, but not all of them. A lot end up floating all around us, in the water, in the air, and in the soil. Yes, they decompose, but the plants do not stop producing them.

And then there is fur and hair, which are polymers of keratins, a protein. Pet lovers live in a cloud of them, from the fur and hair that their pets create and distribute throughout their homes. They are everywhere, too.

Who is looking for these polymers? Someone needs to explain why we don’t all die from all the ills that supposedly exist because of man-made polymers.

I sense that this new anti man-made polymer movement is very much like the movement to eliminate man-made sources of ionizing radiation like nuclear reactors, because they are so harmful, without considering all the naturally generated radiation that also surrounds us like a cloud. When I ask questions about radiation, the usual response is that manmade radiation is somehow “different”, and “natural”, and therefore harmless or not to be worried about. This is absolutely false.

I would also note some other naturally occurring substances that are polymers, such as keratin, chitin, collagen, and gelatin. This from a very quick search for naturally occurring polymers. They may degrade more quickly than man-made polymers, but they are generated by nature in MUCH larger amounts, continuously.

Also those are all completely expected and known by all existing bio-systems, unlike i.e. Teflon. To imply equivalence is pretty dishonest, why would you do that?

Do you know how long it took for something to finally evolve that can break down lignin?

Something like 400-600 million years I think. And we have that to thank for the existence of coal and oil.

people are looking for and studying these natural polymers and i think it’s an interesting thing to study. but disingenuine to say they haven’t been studied or that they are the same as artificial polymers. i’m replying because i think you very impressively distilled why ‘whataboutism’ is harmful even though ‘what about’ is a great question.

what about cellulose? i don’t know. but that’s not an answer about polyethylene. it’s a question worth answering on its own.

Well, a whole lot of these natural polymers have existed longer than, say, mammals. For one, there is a widely believed theory that the large coal beds formed in the carboniferous period were created because plants had evolved a new polymer, lignin, but nothing could yet break that stuff down. Mammals appeared in the late carboniferous, some 300 million years ago. It would not be a far-fetched assumption that something we’ve been living with basically always probably isn’t that harmful.

There are exceptions, sure, and a researched result is certainly better. But it’s basically impossible to research every “what if” scenario.

And comparing natural and man-made sources of ionising radiation is quite disingenuous. We can do absolutely nothing about the former, so why bother? And man-made sources can be vastly more powerful – nothing you might find naturally on Earth gives you acute radiation sickness

Humans have been making things out of plastic for 9000 years, and if you disagree it is probably in part because you don’t appreciate what a carbon based polymer really is.

Most don’t seem to have this problem though and are broken down reasonably.

Brita’s cannot filter down to the micron sizes of most nano/microplastics. The only truly effective water filtration methods for microplastics are reverse osmosis and distillation. Period. The issue with reverse osmosis is that while the process successfully removes all microplastics from the incoming water source, the RO membranes themselves shed their own polymers as they break down over time. So reverse osmosis removes the microplastics but then adds its own to the output water.

Because of this issue, I’ve recently switched our family to a tabletop water distiller. It’s not as convenient as RO, with no water on demand, but it does offer 100% removal of all microplastics from tap water.